Translate this page into:

Marked Disparities in Cardiovascular Disease Mortality by Levels of Happiness and Life Satisfaction in the United States

✉Corresponding author email: hyunjung.lee0001@gmail.com

Abstract

Background:

The impact of happiness and life satisfaction on cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality is not well-studied. Using a longitudinal dataset, we examined the association between levels of happiness/life satisfaction and CVD mortality in the United States.

Methods:

We analyzed the 2001 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) prospectively linked to 2001-2014 mortality records in the National Death Index (NDI) (N=30,933). Cox proportional hazards regression was used to model survival time as a function of happiness, life satisfaction, and sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics.

Results:

In Cox models with 14 years of mortality follow-up, CVD mortality risk was 59% higher (hazard ratio [HR]=1.59; 95% CI=1.26,2.02) in adults with little or no happiness, controlling for age, and 30% higher (HR=1.30; 95% 0=1.01,1.67) in adults with little/no happiness, controlling for sociodemographic, behavioral and health characteristics, when compared with adults reporting happiness most or all of the time. Mortality risk was 81% higher (HR=1.81; 95% 0=1.40,2.34) in adults who were very dissatisfied with their life, controlling for age, and 39% higher (HR=1.39; 95% 0=1.05,1.82) in adults who were very dissatisfied, controlling for all covariates, when compared with adults who were very satisfied.

Conclusions and Implications for Translation:

Adults with lower happiness and life satisfaction levels had significantly higher CVD mortality risks than those with higher happiness and life satisfaction levels. Subjective well-being is an important determinant of CVD mortality.

Keywords

Happiness

Life satisfaction

Cardiovascular

Mortality

Longitudinal

Social determinants

Introduction

Despite being one of the richest nations in the world, the United States ranks lower than many European countries in happiness and life satisfaction, two important indicators of subjective well-being.1,2 Happiness and life satisfaction have long been shown as protective factors for physical health, morbidity, and mortality.2-8 Despite the well-established morbidity studies, studies examining the association between subjective well-being and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality, particularly for the US, are limited and have reported inconsistent findings.4 To contribute further to this growing field of research on happiness and health, we examined the association between happiness/life satisfaction and CVD mortality in the US by using longitudinal cohort data and by considering a wide range of sociodemographic, behavioral, and health risk factors.

Methods

The data source for this study was the 2001 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) prospectively linked to the death certificate data from the National Death Index (NDI).9 As a nationally representative, cross-sectional household interview survey, NHIS provides socio-economic, demographic, and health characteristics of the US civilian, non-institutionalized population. We used the public-use linked NHIS-NDI mortality file, developed by the National Center for Health Statistics, that includes mortality follow- up from the date of survey participation in 2001 through December 31,2014.10

The study sample consisted of 31,376 adults aged ≥ 18 years in the 2001 NHIS. The portion of the sample ineligible for mortality follow-up was eliminated from the analysis. More specifically, approximately 1.41% of the sample had missing data on happiness and life satisfaction, and, as such, were excluded from the analysis. The final eligible sample size was 30,933. All the study covariates except poverty status had less than 1.8% of missing cases. About 21.7% of the cases had missing data on poverty status for which we included a covariate category in the analysis to avoid the loss of a large number of observations.

Our outcome of interest was mortality from CVD (ICD-10 codes: 100-109, 111, 113, 120-151, 160-169), which included deaths from heart disease and stroke. Follow-up time for the deceased was defined by the number of months from the month/ year of interview to the month/year of death. Since NHIS-NDI provides only the quarter of death, we assumed that death occurred in the middle of the quarter, February, May, August, or November.

The independent variables were happiness and life satisfaction. The level of happiness was measured by responses to the question, “During the past 30 days, how often did you feel happy?” Happiness was categorized by none or a little of the time, some of the time, and most or all of the time. Life satisfaction was measured by responses to the question, “In general, how satisfied are you with your life?” Life satisfaction was categorized by very dissatisfied or dissatisfied, satisfied, and very satisfied.

Based on the previous literature, we selected the following covariates for modeling: age, gender, race/ethnicity, nativity/immigrant status, marital status, social support, education, poverty status, homeownership, region, activity limitation, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, alcohol consumption, and hypertension.2,3

We computed age-adjusted mortality rates per 100.0 person-years of exposure by happiness and life satisfaction levels.11 Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to derive relative risks of mortality, controlling for individual characteristics.11 Individuals surviving beyond the follow-up period and those dying from other causes were treated as rightcensored observations. All analyses were conducted by Stata 15, accounting for complex survey design effects.12

Results

Approximately 4.5% of the sample responded that they felt happy none or a little of the time during the past 30 days. About 5.9% of the sample responded that they were very dissatisfied or dissatisfied with their life in general. Compared with men, women reported lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction (Table 1).

| Sample size | Cox model HR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations (weighted %) | Age-adjusted Model 11 | SES-adjusted Model 22 | Fully-adjusted Model 33 | |

| Both sexes combined | ||||

| CVD deaths | 1,218 | |||

| Happiness | 30,933 | 30,933 | ||

| None / a little of the time | 1,575 (4.46) | 1 59***4 (1.26,2.02) | 1.39*** (1.09,1.78) | 1.30** (1.01,1.67) |

| Some of the time | 5,603 (16.88) | 1.33*** (1.15,1.54) | 1.25*** (1.07,1.45) | 1.20** (1.03,1.41) |

| Most or all of the time | 23,755 (78.65) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction5 | 30,928 | 30,928 | ||

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 2,109 (5.92) | 1.81*** (1.40,2.34) | 1.46*** (1.14,1.88) | 1.39** (1.05,1.82) |

| Satisfied | 16,115 (50.20) | 1.34*** (1.17,1.54) | 1.23*** (1.06,1.41) | 1.22** (1.04,1.42) |

| Very satisfied | 12,704 (43.88) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Male | ||||

| Happiness | 13,463 | 13,463 | ||

| None / a little of the time | 649 (4.21) | 1.43* (0.99,2.05) | 1.17 (0.80,1.69) | 1.12 (0.75,1.67) |

| Some of the time | 2,352 (16.36) | 1.47*** (1.17,1.85) | 1.31** (1.04,1.65) | 1.30*** (1.02,1.66) |

| Most or all of the time | 10,462 (79.43) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction | 13,462 | 13,462 | ||

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 868 (5.64) | 1.96*** (1.42,2.7) | 1.40** (1.01,1.94) | 1.32 (0.92,1.90) |

| Satisfied | 6,959 (49.98) | 1.33*** (1.11,1.59) | 1.16 (0.95,1.41) | 1.13 (0.92,1.40) |

| Very satisfied | 5,635 (44.38) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Female | ||||

| Happiness | 17,470 | 17,470 | ||

| None / a little of the time | 926 (4.69) | 1.81*** (1.31,2.50) | 1.60*** (1.15,2.22) | 1.46** (1.04,2.06) |

| Some of the time | 3,251 (17.37) | 1.26** (1,1.58) | 1.15 (0.91,1.44) | 1.10 (0.86,1.39) |

| Most or all of the time | 13,293 (77.94) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction | 17,466 | 17,466 | ||

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 1,241 (6.17) | 1.83*** (1.24,2.71) | 1.52** (1.04,2.23) | 1.47* (0.97,2.23) |

| Satisfied | 9,156 (50.41) | 1.44*** (1.17,1.76) | 1.29** (1.06,1.58) | 1.31** (1.06,1.63) |

| Very satisfied | 7,069 (43.42) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

Data derived from the 2001-2014 NHIS-NDI record linkage study. Ci=confidence interval. 1Cox proportional hazards models were adjusted for age. 2Cox models were adjusted for age, gender race/ethnicity, nativity/immigrant status, marital status, education, poverty status, housing tenure, and region of residence. 3Cox models were adjusted for all variables in model 2 plus social support, activity limitation, bmi, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and hypertension. 4Hazard ratios were statistically significantly different from 1. ***P<0.01; **P<0.05; *P<0.10. 5Cox models for life satisfaction and for other covariates were separately estimated but coefficients of life satisfaction are being reported in the same table

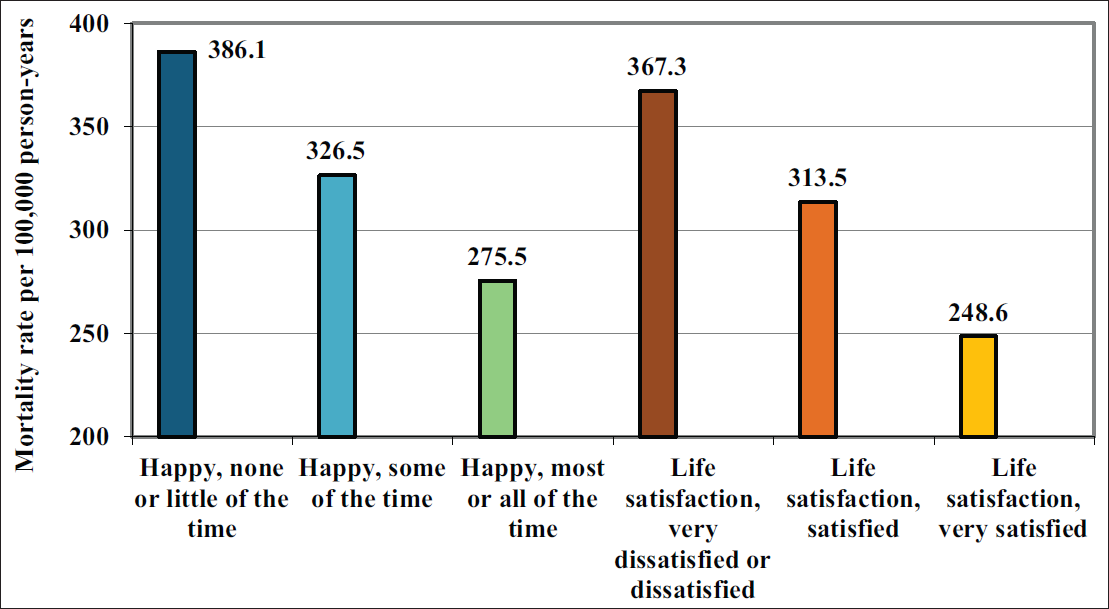

Adults with lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction had higher age-adjusted CVD mortality rates (Figure 1). The CVD mortality rate for adults with “none or a little of the time” happiness was 386.1 deaths per 100,000 person-years, 40% higher than the mortality rate of 275.5 for adults with “most or all of the time” happiness. The CVD mortality rate for adults who were very dissatisfied or dissatisfied with their life was 48% higher than the rate for those who were very satisfied.

- Age-adjusted Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) Mortality Rates per 100,000 Person-Years by Levels of Happiness and Life Satisfaction, United States, 2001-2014

- Source: Data derived from the 2001-2014 NHIS-NDI Record Linkage Study. The mortality rate ratio between low and high happiness levels, none/little of the time and most/all of the time was RR = 1.40; 95% CI = 1.09, 1.71; p<0.01. The mortality rate ratio between low and high life satisfaction levels, was RR = 1.48; 95% CI = 1.15, 1.81; p<0.01

In Cox regression models, the age-adjusted CVD mortality risk was 59% higher (hazard ratio [HR]=1.59; 95% CI=1.26, 2.02) in adults with “none or a little of the time” happiness, compared with adult with “most or all of the time” happiness (Table 1, Model 1). After controlling for socioeconomic and demographic covariates, the mortality risk was 39% higher (HR=1.39; 95% 0=1.09, 1.78) in adults with “none or a little of the time” happiness, compared with adults with “most or all of the time” happiness (Table 1, Model 2). After controlling for all covariates, the mortality risk was 30% higher (HR=1.30; 95% CI=1.01, 1.67) in adults with “none or a little of the time” happiness, compared to those with “most or all of the time” happiness (Table 1, Model 3).

In Cox regression models, the age-adjusted CVD mortality risk was 81% higher (HR=1.81; 95% CI=1.40, 2.34) among adults who were very dissatisfied or dissatisfied with their life, compared with adults who were very satisfied (Table 1, Model 1). After controlling for socioeconomic and demographic covariates, the CVD mortality risk was 46% higher (HR=1.46; 95% CI=1.14, 1.88) in adults who were very dissatisfied or dissatisfied, compared with adults who were very satisfied (Table 1, Model 2). After controlling for all covariates, the CVD mortality risk was 39% higher (HR=1.39; 95% CI=1.05, 1.82) in adults who were very dissatisfied or dissatisfied with their life, compared with adults who were very satisfied (Table 1, Model 3). The association between happiness/life satisfaction and fully-adjusted CVD mortality risks was stronger for women than for men (Table 1).

We tested the issue of reverse causality by comparing the analysis between the sample with and without baseline history of heart disease or stroke diagnoses. We found in the fully-adjusted model no substantial association between happiness and CVD mortality for both respondents with and without heart disease or stroke, while the association between life satisfaction and CVD mortality was statistically significant only among those with a history of heart disease or stroke diagnosis (Table 2). We conducted sensitivity analyses to evaluate temporal robustness of happiness/life satisfaction by re-estimating models using 2-year, 5-year, and 10-year follow-up times. The longer follow-up dilutes the mortality impact of baseline happiness and life satisfaction, as they are expected to differ from their baseline levels over the longer follow-up (Table 3).

| Age-adjusted model | SES-adjusted model | Fully-adjusted model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults without the heart disease 1 or stroke diagnosis at baseline | |||

| Happiness | 26,994 | 26,994 | 26,994 |

| None / a little of the time | 1.50** (1.07,2.1) | 1.27 (0.89,1.81) | 1.21 (0.87,1.71) |

| Some of the time | 1.26** (1.03,1.54) | 1.18 (0.96,1.44) | 1.14 (0.91,1.42) |

| Most or all of the time | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction | 27,003 | 27,003 | 27,003 |

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 1.65*** (1.15,2.36) | 1.29 (0.9,1.83) | 1.2 (0.82,1.75) |

| Satisfied | 1.26** (1.05,1.51) | 1.13 (0.94,1.36) | 1.09 (0.89,1.34) |

| Very satisfied | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Adults with history of heart disease or stroke diagnosis at baseline | |||

| Happiness | 3,939 | 3,939 | 3,939 |

| None / a little of the time | 1.43** (1.01,2.03) | 1.30 (0.92,1.85) | 1.28 (0.88,1.86) |

| Some of the time | 1.26** (1.01,1.57) | 1.19 (0.95,1.49) | 1.21 (0.95,1.53) |

| Most or all of the time | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction | 3,925 | 3,925 | 3,925 |

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 1.61** (1.12,2.31) | 1.40* (0.96,2.04) | 1.44* (0.96,2.16) |

| Satisfied | 1.35*** (1.1,1.66) | 1.25** (1,1.56) | 1.28** (1.02,1.6) |

| Very satisfied | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

Source: Data derived from the 2001-2014 NHIS-NDI Record Linkage Study. 1Coronary heart disease, congenital heart disease, heart attack, and any other heart condition/ disease. ***p<0.01; **p<0.05; *p<0.10

| Age-adjusted model | SES-adjusted model | Fully-adjusted model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Year mortality follow-up | |||

| Happiness | |||

| None / a little of the time | 1.65 (0.93,2.94)† | 1.44 (0.82,2.52) | 1.56 (0.87,2.79) |

| Some of the time | 1.35 (0.94,1.94) | 1.27 (0.89,1.82) | 1.32 (0.92,1.89) |

| Most or all of the time | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction | |||

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 1.12 (0.61,2.06) | 0.91 (0.52,1.59) | 0.99 (0.53,1.83) |

| Satisfied | 1.29 (0.93,1.8) | 1.21 (0.85,1.72) | 1.28 (0.9,1.82) |

| Very satisfied | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 5-Year mortality follow-up | |||

| Happiness | |||

| None / a little of the time | 2.15*** (1.52,3.06) | 1.88*** (1.32,2.69) | 1.78*** (1.25,2.54) |

| Some of the time | 1.42** (1.13,1.78) | 1.33** (1.06,1.67) | 1.27** (1,1.6) |

| Most or all of the time | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction | |||

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 2.03*** (1.4,2.93) | 1.62** (1.11,2.35) | 1.55** (1.04,2.31) |

| Satisfied | 1.56*** (1.24,1.95) | 1.42*** (1.12,1.8) | 1.42*** (1.12,1.8) |

| Very satisfied | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 10-Year mortality follow-up | |||

| Happiness | |||

| None / a little of the time | 1.72*** (1.3,2.27) | 1.47** (1.1,1.97) | 1.39** (1.03,1.86) |

| Some of the time | 1.37*** (1.16,1.61) | 1.28*** (1.07,1.51) | 1.22** (1.02,1.46) |

| Most or all of the time | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Life satisfaction | |||

| Very dissatisfied or dissatisfied | 2.04*** (1.56,2.69) | 1.66*** (1.26,2.18) | 1.60*** (1.19,2.14) |

| Satisfied | 1.50*** (1.28,1.75) | 1.37*** (1.16,1.62) | 1.37*** (1.16,1.62) |

| Very satisfied | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

Data derived from the 2001-2014 NHIS-NDI Record Linkage Study. ***p<0.01; **p<0.05; *p<0.10.

Discussion

In this large prospective study of 30,933 US adults using a long mortality follow-up of 14 years, we found that adults with lower levels of happiness and life satisfaction had substantially higher CVD mortality risks. Even after controlling for several sociodemographic, health status, and behavioral characteristics, significantly higher risks of CVD mortality existed for the total population who did not experience happiness or were dissatisfied, compared with those who reported happiness most or all of the time or those who were very satisfied with their lives. Our study contributes to the empirical literature that shows happiness and life satisfaction are inversely related to CVD mortality.

The findings of our study are consistent with those from previous studies.2,4-8 For example, Martin-Maria and colleagues found that the pooled HR for the effect of subjective well-being including happiness and life satisfaction on coronary heart disease or CVD mortality ranged from 0.60 to 1.04; in their meta-analysis, only 10 studies estimated CVD- related mortality risks among 90 studies.4 Although these studies used job satisfaction, level of emotional vitality, life enjoyment as measures of subjective well- being, they found an association between subjective well-being and CVD morality.6-8 Furthermore, in our full model with controls for sociodemographic characteristics, health status, and behavioral risk factors of smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, and hypertension, the adjusted risk of all-CVD mortality associated with dissatisfaction was 1.39, compared with 1.61 with low level of life enjoyment in Shirai study with similar covariates.8

Our study has provided evidence of a substantial link between happiness/life satisfaction and CVD mortality, but does not shed light on behavioral or biological mechanisms through which happiness/ life satisfaction might affect CVD mortality. One potential mechanism is that individuals with greater happiness/life satisfaction levels have healthier lifestyles, including greater physical activity, higher consumption of fruits and vegetables, less drinking or smoking, and more preventive care, resulting in reduced morbidity and mortality risks.2 The other mechanisms might involve biological processes of happiness relevant to health such as biomarker neuroendocrine, inflammation, cardiovascular disease, metabolic, or allostatic load.2 There are a wide range of risk factors for happiness/life satisfaction, such as personality, genetics, stress exposure, social support or network, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, marital status, physical activity, and health status.2 In our analysis, we controlled for several of these factors, which are associated with both happiness/life satisfaction and CVD mortality in an expected manner.2,3 Further research is needed to examine differential associations between happiness or life satisfaction and CVD mortality by these factors or pathways.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, residual confounding and reverse causality might have affected our study findings. While we controlled for baseline self-reported health status, activity limitation, BMI, smoking, and hypertension, there could have been other potential confounders such as neighborhood environments or periods of economic downturn. Chronic poor health itself may be a determinant of self-reported happiness and life satisfaction at the survey time. Although we controlled for several baseline health factors, the issue of reverse causation cannot be fully addressed. Second, our measures of happiness and life satisfaction might not capture all aspects of subjective well-being, including optimism, realization of personal potential and fulfillment of life goals or specific measures of happiness in different domains such as marriage/family, jobs, and finances. Third, because the NHIS excludes the institutionalized population, who may have lower happiness/life satisfaction and higher mortality levels, CVD mortality risks associated with happiness/ life satisfaction might have been underestimated. Fourth, all covariates in the NHIS-NDI database were time-fixed at the baseline as of the survey date. Several covariates such as socioeconomic status, health status, health-risk behaviors, and happiness/ life satisfaction could have varied over the 14- year follow-up, which would have influenced their estimated impacts on CVD mortality. Further studies are needed to evaluate the temporal robustness of happiness/life satisfaction patterns in CVD mortality using time-varying covariates.

Conclusions and Implications for Translation

With 14 years of mortality follow-up in a large, nationally representative study of 30,933 US adults aged ≥18 years, we found that people with low levels of happiness and life satisfaction had, respectively, 59% and 81% higher age-adjusted risks of CVD mortality compared to those with high levels of happiness and life satisfaction. The association between happiness/ life satisfaction and CVD mortality remained marked and statistically significant even after controlling for several sociodemographic, behavioral, and health characteristics. Our study findings indicate happiness/life satisfaction to be an important predictor of CVD mortality; they underscore the significance of enhancing subjective well-being in the general population as a potential strategy for reducing CVD mortality. Social determinants such as education, income, work status, job security, housing conditions, social support, social environment, and access to green spaces and quality health care are key to enhancing happiness and life satisfaction. Policies addressing these social determinants will not only promote happiness and well-being among people and but may also lead to reductions in CVD mortality.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest:

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this publication are solely the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration, nor does mention of the department or agency names imply endorsement by the US Government.

Financial Disclosure:

The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Ethical approval:

The study was deemed exempt from Institutional Review Board approval as it utilized a de-identified public use dataset.

Acknowledgment:

None.

Funding source:

Dr. Hyunjung Lee was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Health Resources & Services Administration - Office of Planning, Analysis and Evaluation (HRSA-OPAE) and Office of Health Equity (OHE), administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE) through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and HRSA.

References

- Helliwell JF, Layard R, Sachs J, De Neve JE, eds. World Happiness Report 2020. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network; 2020.

- Happiness and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):339-359.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happiness and life satisfaction prospectively predict self-rated health, physical health, and the presence of limiting, long-term health conditions. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(1):18-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The impact of subjective well-being on mortality: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies in the general population. Psychosom Med. 2017;79(5):565-575.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Positive and negative affect and risk of coronary heart disease: Whitehall II prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337(7660):a118.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Change in job satisfaction, and its association with self-reported stress, cardiovascular risk factors and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(10):1589-1599.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emotional vitality and incident coronary heart disease: benefits of healthy psychological functioning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1393-1401.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perceived level of life enjoyment and risks of cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality: the Japan public health center-based study. Circulation. 2009;120(11):956-963.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 6.4 [dataset] 2019

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 2015 Public-Use Linked Mortality Files. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015

- [Google Scholar]

- Life Table Techniques and Their Applications. Orlando, Fla: Academic Press; 1987.