Translate this page into:

Late Dementia Diagnosis Among Elderly Minority Populations in the United States: Causes, Effects, and Addressing Inequities

*Corresponding author: Elizabeth Armstrong-Mensah, PhD, Department of Health Policy and Behavioral Sciences, Georgia State University, School of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia, United States. Tel: +404-413-2330 earmstrongmensah@gsu.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Armstrong-Mensah E, Adjini M, Pringle-Weston B, Akosah A, Addo R. Late dementia diagnosis among elderly minority populations in the United States: Causes, effects, and addressing inequities. Int J Transl Med Res Public Health. 2024;8:e010. doi: 10.25259/IJTMRPH_38_2024

Abstract

Millions of elderly people aged 65 years and above are living with dementia in the United States (US). While dementia cases are highest among minority racial groups in the US, this population often receives late or missed diagnosis compared to their White counterparts, leading to glaring disparities in dementia incidence, prevalence, and health outcomes. With dementia cases anticipated to increase in the future, delays in diagnosis are likely to create personal and a greater public health burden over time for elderly minority populations. We conducted an ecological study of the relationship between the causes, effects, and outcomes of late dementia diagnosis minority populations in the US. We searched Google, PubMed, and Google Scholar, and reviewed 80 English articles related to late dementia diagnosis among minority populations in the US published from 2008 to 2024. We found that the timely and accurate diagnosis of dementia will enable minority patients to receive prompt and effective treatment to avert or slow down the condition, reduce the cost of care significantly, and help the elderly to maintain cognitive health for a greater duration before the condition becomes severe. It will also give them the opportunity to contribute toward their care planning process.

Keywords

Late Dementia

Dementia Diagnosis

Racial Groups

Inequities

United States

Alzheimer’s

Minority Health

INTRODUCTION

Aging is a natural biological process that affects all human beings. Characterized by time-related deterioration of physiological functions, aging predisposes the elderly to a myriad of health conditions including dementia. Dementia is a syndrome caused by conditions and other related disorders that over time, destroys nerve cells and damages the brain, causing a decline in cognitive ability that goes beyond the biological consequences associated with aging.[1] Dementia involves the progressive loss of neurons and brain function due to the accumulation of abnormal proteins such as amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the brain, which can lead to neurodegeneration.[2] While consciousness is not affected when one has dementia, there may be occasional changes in mood, emotional control, behavior, or motivation.[1]

Dementia is a global health issue. It is currently the seventh leading cause of death worldwide, and one of the main causes of disability and dependency among the elderly.[1] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there are over 50 million people living with dementia globally, and this number is expected to triple by 2050.[1] In the United States (US), an estimated seven million people aged 65 years and above had dementia in 2020. If current demographic and health trends continue, over nine million Americans could have dementia by 2030 and about 12 million by 2040.[3]

Elderly minority populations in the US often have a missed dementia diagnosis or are diagnosed late for the condition. This has the tendency to worsen disability, reduce treatment effectiveness, impede timely care, and increase healthcare costs.[4] The early detection and accurate diagnosis of dementia among the elderly is crucial because it can result in the prompt seeking of appropriate treatment, care, interventions, and support, and can also help the elderly plan ahead while they are still able to make important decisions about their health. Additionally, early detection of dementia can reduce the cost of care significantly and help the elderly to maintain cognitive health for a greater duration before the condition becomes severe.[5]

We conducted an ecological study of the relationship between the causes, effects, and outcomes of late dementia diagnosis among minority populations in the US. We searched Google, PubMed, and Google Scholar, and reviewed 80 English articles related to late dementia diagnosis among minority populations in the US published from 2008 to 2024. We conducted our search using a combination of keywords including late dementia, dementia diagnosis, racial groups, inequities, and United States. Fifty articles met our study’s inclusion criteria.

Types of Dementia and Symptoms

There are several types of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, and mixed dementia. Each type has distinct features, mode of progression, and associated signs and symptom.[6] Some types of dementia are common while others are rare.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for about 80% of all diagnoses globally.[7] AD is a neurodegenerative disorder that affects memory, thinking, behavior, and general cognitive ability. Pathological features in the brain tissues of AD patients manifest in the form of raised levels of amyloid-β (Aβ) proteins consisting of senile plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) aggregations of neurofibrillary tangles.[8] Signs and symptoms of AD vary from person to person but typically include a decline in non-memory aspects of cognition, such as finding the right words, trouble understanding visual images and spatial relationships, and impaired reasoning or judgment.[9] While a new drug has just been approved in the US for treating AD (Aducanumab), other treatments are also available that can ease symptoms.[10]

Vascular dementia (VaD) is the second most common type of dementia, accounting for about 15–20% of dementia cases in the US and Europe.[11] This type of dementia presents in the form of significant cognitive impairment occurring mainly due to vascular injury to the brain. With VaD, there are changes in memory, thinking, and behavior. Cognition and brain function are affected by the size, location, and number of vascular changes that occur. Like AD, there is also no cure for VaD, however, active physical and mental therapeutics can help to delay cognitive decline.[12]

Lewy body accounts for 4–8% of dementia cases.[13] This form of dementia is common and is caused by neuronal cell death from aggregates of misfolded protein, α-synuclein in areas of the nervous system and the brain.[14] Manifestation of the disease includes cognitive, neuropsychiatric, and autonomic symptoms, which are difficult to manage, as treatment may address one symptom and exacerbate another.[13] Frontotemporal dementia is a group of clinical syndromes that develop as a result of frontotemporal lobar degeneration leading to progressive changes in behavior, executive function, or language.[15] There is no treatment available for this form of dementia, however new therapies for genetic forms of this disease are moving into clinical trials.[16] Mixed dementia is a heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder caused by the coexistence of AD and VaD. There are controversies over the concept validity of mixed dementia. This has slowed down progress in research and the development of therapeutics for this disorder.[17]

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE OF DEMENTIA BY RACE

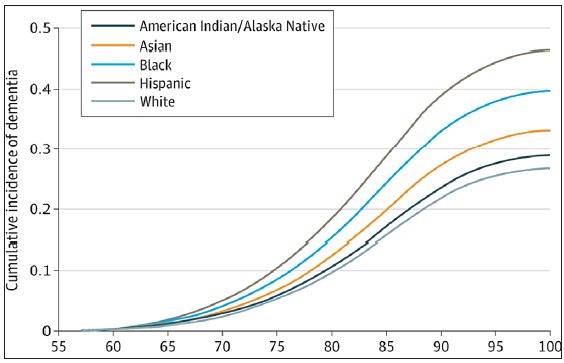

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), AD and other forms of dementia are increasing in prevalence.[18] In 2023, an estimated 6.7 million Americans aged 65 and older were living with Alzheimer’s dementia, and about 73% of that population was 75 years or older.[19] Also in 2023, approximately one in nine people (10.8%) aged 65 years and above had Alzheimer’s dementia. The disorder increased with age, with about 5.0% of people aged 65 to 74, 13.1% of people aged 75 to 84 years, and 33.3% of people aged 85 and older living with the disorder in the US.[20] The cumulative incidence of dementia in the US by race and age, and how the curve for the racial groups begins to diverge around age 65 is shown in Figure 1.[21] As a result of the increasing number of elderly people in the US, particularly those aged 85 and older, the annual number of new cases of AD and other dementias is projected to double by 2050.[22] While studies on the prevalence of younger onset dementia in the US are limited, some researchers believe that about 110 of every 100,000 people aged 30–60 years, or better still, about 200,000 Americans, have younger-onset dementia.[19]

- Cumulative incidence of dementia by racial group. Source: Kornblith Race and ethnicity with incidence of dementia among older adults.

Although White people account for majority of the over 5 million people in the US with AD, combined evidence from available studies show that African Americans and Hispanics are at higher risk.[23] A study conducted by Kornblith et al. in 2022 on the association of race and ethnicity with the incidence of dementia among older adults in the US found that the incidence of dementia is highest among older Hispanics followed by African Americans, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and Asian Americans. The study also found that Whites had the lowest dementia incidence rate.[21] Statistics from an epidemiology cohort study conducted by Potter et al. indicates that African Americans and Hispanics are about twice and 1.5 times as likely to have dementia respectively, compared to Whites of the same age.[24] The CDC forecasts that by 2060, the dementia burden in the US will double, with four times as many cases occurring among African Americans and seven times as many among Hispanics.[18]

Based on Pool et al.’s projections, between 2020 and 2025, every state across the US (excluding the District of Columbia) will have experienced an increase of at least 6.7% in the number of Americans aged 65 and older with Alzheimer’s dementia.[25] The prevalence estimates for 2020 and 2025, and changes between these two years, are shown in Table 1.

| State | Projected number with Alzheimer’s (in thousands) | Percentage increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2025 | 2020–2025 | |

| Alabama | 96 | 110 | 14.6 |

| Alaska | 8.5 | 11 | 29.4 |

| Arizona | 150 | 200 | 33.3 |

| Arkansas | 58 | 67 | 15.5 |

| California | 690 | 840 | 21.7 |

| Colorado | 76 | 92 | 21.1 |

| Connecticut | 80 | 91 | 13.8 |

| Delaware | 19 | 23 | 21.1 |

| District of Columbia | 8.9 | 9 | 1.1 |

| Florida | 580 | 720 | 24.1 |

| Georgia | 150 | 190 | 26.7 |

| Hawaii | 29 | 35 | 20.7 |

| Idaho | 27 | 33 | 22.2 |

| Illinois | 230 | 260 | 13.0 |

| Indiana | 110 | 130 | 18.2 |

| Iowa | 66 | 73 | 10.6 |

| Kansas | 55 | 62 | 12.7 |

| Kentucky | 75 | 86 | 14.7 |

| Louisiana | 92 | 110 | 19.6 |

| Maine | 29 | 35 | 20.7 |

| Maryland | 110 | 130 | 18.2 |

| Massachusetts | 130 | 150 | 15.4 |

| Michigan | 190 | 220 | 15.8 |

| Minnesota | 99 | 120 | 21.2 |

| Mississippi | 57 | 65 | 14.0 |

| Missouri | 120 | 130 | 8.3 |

| Montana | 22 | 27 | 22.7 |

| Nebraska | 25 | 40 | 14.3 |

| Nevada | 49 | 64 | 30.6 |

| New Hampshire | 26 | 32 | 23.1 |

| New Jersey | 190 | 210 | 10.5 |

| New Mexico | 43 | 53 | 23.3 |

| New York | 410 | 460 | 12.2 |

| North Carolina | 180 | 210 | 16.7 |

| North Dakota | 15 | 16 | 6.7 |

| Ohio | 220 | 250 | 13.6 |

| Oklahoma | 67 | 76 | 13.4 |

| Oregon | 69 | 84 | 21.7 |

| Pennsylvania | 280 | 320 | 14.3 |

| Rhone Island | 24 | 27 | 12.5 |

| South Carolina | 95 | 120 | 26.3 |

| South Dakota | 18 | 20 | 11.1 |

| Tennessee | 120 | 140 | 16.7 |

| Texas | 400 | 490 | 22.5 |

| Utah | 34 | 42 | 23.5 |

| Vermont | 13 | 17 | 30.8 |

| Virginia | 150 | 190 | 26.7 |

| Washington | 120 | 140 | 16.7 |

| West Virginia | 39 | 44 | 12.8 |

| Wisconsin | 120 | 130 | 8.3 |

| Wyoming | 10 | 13 | 30.0 |

Source: Created from data provided to the Alzheimer’s Association by Pool et al. 2016.

Late Dementia Diagnosis by Race

While underdiagnosed dementia is a problem across all racial groups in the US, it is more prevalent among racial minorities. Although the rate of AD and other dementias is higher among African Americans and Hispanics than among Whites, these minority racial groups are less likely than Whites to receive a diagnosis at all, or an early diagnosis of the condition.[23] According to extant literature, while African Americans are about two times more likely than Whites to have AD and other dementias, they are only 34% more likely to have a diagnosis, and while Hispanics are about one and one-half times more likely than Whites to have AD and other dementias, they are only 18% more likely to be diagnosed.

Data from the 2016 Health and Retirements Study showed that less than 50% of older adults (65 years and above) with dementia in the US reported being told by a physician about their condition. Per that same study, more African Americans and Hispanics than Whites were unaware of their dementia status.[26] In their 2022 study on dementia diagnosis disparities by race among 3,966 participants who were 70 years old and above, Lin et al. observed that a higher proportion of African Americans and Hispanics had a missed or delayed clinical dementia diagnosis compared to Whites (46% and 54% respectively, vs. 41%, p < 0.001).[12] They also noted that the estimated mean diagnosis delay was 34.6 months for African Americans and 43.8 months for Hispanics, compared to 31.2 months for Whites. Based on their findings, Lin et al. concluded that because African Americans and Hispanics experience a missed diagnosis of dementia, and longer diagnosis delays, there is a greater likelihood that these racial groups will end up with more advanced forms of dementia. In their study on dementia diagnosis disparities by race and ethnicity, Lin et al. found that African Americans and Hispanics are at greater odds of having a delayed dementia diagnosis compared to their White counterparts.[12]

Using Medicaid and Medicare data from four states, Gilligan et al. noticed that there were racial disparities in the treatment of dementia patients, with Whites more likely to be exposed to medication therapy than their African American counterparts.[4] In a prior study, Zuckerman et al. (2008) also observed this. In their study, Zuckerman et al. found that Whites had an average of 7.7 office visits during the observation period, compared to 6.9 visits by minorities.[27] Based on their results, they stated that the difference in access to medication therapy among the races could be due to the reduced contact with physicians by minority patients. Disparities in office visits by minorities with dementia have been linked to provider bias and culturally incompetent care.

CAUSES OF LATE DEMENTIA DIAGNOSIS

Some contributing factors to the late or missed diagnosis of dementia among minority populations in the US include the lack of patient and caregiver dementia awareness, inequities in access to care, socioeconomic factors, the administration of inappropriate dementia screening tests, and physician bias and educational needs.[16] According to a 2014 Florida Department of Elder Affairs survey, over 75% of elderly people with dementia did not receive a dementia diagnosis until at least one year after their symptoms began. This was because of a lack of general awareness of the condition, the fact that some elderly people thought their symptoms were part of normal aging, and also because they thought nothing could be done about what they were experiencing. Based on the results of their study, Wackerbarth and Johnson revealed that caretakers of elderly minority populations in rural areas in the US, have lower levels of education and knowledge about dementia, contributing to delayed screening and diagnosis.[28]

Inequities in access to health care due to the lack of health insurance coverage, proximity to a medical facility, mistrust of the system, racism, and a lack of diversity in the healthcare workforce also increases the risk of delayed or misdiagnosed dementia among elderly minority populations.[29] In a primary care environment where provider–patient interactions tend to be brief and patients are not engaged in their care, early symptoms of dementia, such as memory impairment, can be missed during routine office visits.

The lack of access to health insurance due to socioeconomic factors makes it difficult for most elderly African Americans to seek dementia screening early, increasing medical and caregiving costs when they eventually get diagnosed. The estimated annual medical and caregiving cost associated with dementia based on data from the Health and Retirement Study, is about $20,000 higher for Hispanics and African Americans than for Whites.[30] The ability of the US government to finance and deliver long-term care to patients with dementia is a challenge that policymakers are yet to address.[17] While government efforts through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) are able to assist with some of the costs associated with dementia, they do not go far enough.[31] While Medicare pays for time-limited care (typically for a few days per year) after a hospital stay or an acute episode, it does not cover long-term care.[17] Private long-term care insurance does not help to fill in the gap, as about only 8% of Americans can afford such coverage.[32] How elderly minorities living with dementia and their families finance the high costs of care are urgent issues that need to be addressed.[30]

Studies have revealed that the tests used for dementia screening and diagnosis in clinical settings are less accurate for racial minorities. According to Mast et al. and Wood et al. the Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) commonly used for minority populations has lower specificity and thus, often leads to the overdiagnosis of dementia among African Americans.[33,34] In their study on racial differences in the recognition of cognitive dysfunction in older persons, Rovner et al. indicated that the cognitive tests used for dementia diagnosis was unsuitable for minority populations. They found that caregivers of African American patients reported lower degrees of cognitive decline after completing the Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE), than the caregivers of White patients with similar impairments, which to them, contributed to dementia underdiagnosis.[35]

Per some researchers, the late diagnosis of dementia among the elderly is due to the lack of physician education about the disease, specifically physician ability to distinguish cognitive changes that are normal to aging from the symptoms of dementia, as well as physician concerns about the consequences of a dementia misdiagnosis on patients and their families.[36] Based on their study on dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries, Lin et al. stated that although most seniors (>92%) with probable dementia in their study sample had seen a doctor in the last two years (with an average of 13 visits), African Americans and Hispanics had the lowest Medicare annual wellness visits.[12] Also emphasizing the role of race, Drabo et al. reported that underrepresented racial groups were less likely to receive follow-up care by dementia specialists (e.g., neurologists and psychiatrists) after receiving a clinical diagnosis.[37]

EFFECTS OF LATE DEMENTIA DIAGNOSIS ON THE ELDERLY

A study conducted by Clark et al. revealed that due to the delays in dementia diagnosis among African Americans in the US, the time between the onset of dementia symptoms and diagnosis is about seven years, allowing the disease to significantly progress among this population before care and treatment are sought.[38]

Late dementia diagnosis has been linked to the inability of the elderly to perform basic daily tasks such as eating, bathing, or getting dressed. It also causes a loss in the ability to communicate, characterized by incoherent speech and the inability to understand speech. In their systematic review of cognitive impairment, Jekel et al. found that the decline in cognitive function in dementia patients is often marked by severe memory loss, confusion, and impaired judgment. Consequently, patients struggle with recognizing familiar faces, places, and objects.[39] Mitchell et al. also found that patients with dementia experience a steady decline in motor function, which sometimes leads to challenges with movement, balance, coordination, and a heightened risk for falls and injuries.[40]

In addition to cognitive and physical impairments, late dementia diagnosis can have significant emotional and psychological effects on those impacted. In their study on behavioral disturbances in geropsychiatric inpatients with dementia, Kunik et al. observed that restlessness, aggression, and depression were typical symptoms among individuals with late-stage dementia, and that the symptoms made it difficult for caregivers to provide adequate care and support.[41] Schulz et al. reported that caregivers of individuals with late-stage dementia have high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression.[42] According to McCurry et al. (2017), patients with late dementia diagnosis often experience disrupted sleep patterns including insomnia, fragmented sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness, which exacerbate cognitive decline and contribute to negative behavioral issues.[43]

The late diagnosis of dementia can also lead to increased healthcare costs. In the US, most African Americans and Hispanics are typically diagnosed during the later stages of dementia, causing them to utilize more hospital, physician, and home health services, and to incur higher financial burdens compared to Whites who are often diagnosed early. In 2014, the average per-person Medicare payment for African Americans with AD and other dementias was 35% higher than for Whites with AD and was 7% higher for Hispanics than for Whites.[23] In 2022, the total per person healthcare cost and long-term care cost from all sources for Medicare beneficiaries with AD or other dementias, was about three times ($43,444) that of Medicare beneficiaries in the same age group not living with AD or other dementias ($14,593). Irrespective of Medicare and other sources of financial assistance in the US, individuals with AD and other dementias, have to deal with high out-of-pocket costs such as deductibles, copayments, and coinsurance for services not covered by Medicare.[19] In 2023, among Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer’s or other dementias, African Americans had the highest unadjusted Medicare payments per person per year, while White beneficiaries had the lowest payments ($27,814 vs. $22,306 respectively) [Table 2]. The highest difference in service payment was for hospital care, with African American Medicare beneficiaries incurring 1.6 times in cost ($9,006) than White beneficiaries ($5,791).[44] This economic burden highlights the importance of prioritizing minority populations at risk for early dementia screening and diagnosis.[45] Missed or delayed dementia diagnosis creates lost opportunities for treatment, which can lead to a more advanced form of the condition, and sometimes death.[12]

| Race | Total medicare payments per person | Hospital care | Physician care | Skilled nursing care | Home health care | Hospice care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 22,306 | 5,791 | 3,725 | 3,297 | 1, 912 | 4,137 |

| Black/African American | 27,814 | 9,006 | 4,528 | 4,338 | 1, 970 | 2,910 |

| Hispanic | 25,729 | 7,836 | 4,298 | 3,763 | 2,371 | 3,416 |

| Other | 22,864 | 7,260 | 3,917 | 3,663 | 1, 959 | 2,817 |

Data obtained from unpublished data from the National 100% sample medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries for 2019.

Addressing Late Dementia Diagnosis

Understanding the causes of late dementia diagnosis among elderly minority populations in the US is the first step toward addressing the issue. Providing education on the early signs of dementia and available treatment options to the elderly and their caregivers can enhance their awareness of the condition, prompt early screening, give people living with dementia access to treatments and interventions, build a care team, enable people living with dementia to participate in support services, and enroll in clinical trials.[18] The elderly and their caregivers can also create systems that will enable them to better manage medications, receive counseling, and attend to challenges brought on by chronic conditions associated with dementia. According to Lo, education on dementia is a public health priority, in that, it influences health literacy and resultant health-seeking behaviors such as screening and testing.[46]

Mandated tailored training aimed at strengthening the competencies of professionals who provide health care and other services to elderly minority populations can help to improve upon their ability to screen for and detect dementia early.[18] Although protocols, algorithms, and policies to enable dementia detection and treatment after the administration of brief cognitive assessment have been released by established national medical organizations,[47] few healthcare providers use these to assess cognition among persons over 65 years old.[48] To be able to accurately diagnose dementia, healthcare professionals need to be able to recognize the pattern of loss of skills and function, and what a person without dementia should be able to do.[49]

Making health care affordable, equitable, and easily accessible by all, regardless of socioeconomic status, will enable elderly minority populations to seek frequent medical care, which could lead to reduced delays in dementia screening and diagnosis. While State legislatures in the US have begun exploring options for filling the financing gap, more needs to be done and quickly. In addition to coming up with strategies to fill the financing gap, policymakers in the US need to focus on putting in place policies that will expressly reduce disparities in dementia diagnosis among minority populations, make healthcare coverage available to all, increase mental healthcare workforce diversity, and promote dementia awareness.

CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR TRANSLATION

The timely and accurate diagnosis of dementia among minority elderly populations in the US is highly important as it can cause this population to save on long-term care costs,[48] obtain prompt and effective care and treatment for potentially reversible causes, and have adequate time with their families to plan for their future care. The timely and accurate diagnosis of dementia among minority elderly populations in the US will also provide opportunities for this population to participate in clinical trials, which may slow down the progression of their symptoms.[14,50]

Key Messages

-

Alzheimer’s Disease and other forms of dementia are increasing in prevalence in the US.

-

Minority racial groups in the US receive late or missed diagnoses compared to their White counterparts.

-

The timely and accurate diagnosis of dementia will enable minority racial groups in the US to receive prompt and effective treatment to avert or slow down the condition, reduce the cost of care significantly, and help with the maintenance of cognitive health.

-

Policymakers in the US need to come up with recommendations aimed at reducing disparities in dementia diagnosis among minority populations.

-

Recommendations should include policy changes in healthcare coverage for all, the implementation of initiatives to increase diversity in the dementia healthcare workforce, and the establishment of community outreach programs to raise awareness and education about dementia.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial Disclosure

Nothing to declare.

Funding/Support

There was no funding for this study.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Declaration of Patient Consent

Not applicable.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for Manuscript Preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Disclaimer

None.

REFERENCES

- Dementia. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2023. [Assessed 2023 May 28]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Machine learning for modeling the progression of Alzheimer’s disease dementia using clinical data: A systematic literature review. JAMIA Open.. 2021;4(3)

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of changes in population health and mortality on future prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in the United States. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(1):S38-S47.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Racial and ethnic disparities in Alzheimer’s disease pharmacotherapy exposure: An analysis across four state Medicaid populations. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother.. 2012;10(5):303-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost-effective community-based dementia screening: A markov model simulation. Int J Alzheimers Dis.. 2014;103138:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Chicago (IL): Alzheimer’s Association; 2021. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/alz.12328

- Diversity and disparities in dementia diagnosis and care: A challenge for all of us. JAMA Neurol.. 2021;78(6):650-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurol.. 2018;14(7):399-415.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease Fact Sheet. Chicago (IL): Alzheimer’s Association; 2023. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet

- A new Alzheimer’s drug has been approved. But should you take it?. Boston (MA): Harvard University, Harvard Medical School; 2021. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/a-new-alzheimers-drug-has-been-approved-but-should-you-take-it-202106082483

- Modifiable risk factors and prevention of dementia: What is the latest evidence? JAMA Intern Med.. 2018;178(2):281-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dementia diagnosis disparities by race and ethnicity. Med Care.. 2021;59(8):679.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Aff.. 2015;34(10):1642-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease: A literature review on benefits and challenges. J Alzheimers Dis.. 2016;49(3):617-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public Health.. 2022;7(2):e105-e125.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: Prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord.. 2009;23(4):306-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Reducing the Impact of Dementia in America: A Decadal Survey of the Behavioral and Social Sciences. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2021. p. :360.

- Minorities and women are at greater risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/publications/features/Alz-Greater-Risk.html

- About Alzheimer’s Disease. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/aging/alzheimers-disease-dementia/about-alzheimers.html

- Population estimate of people with clinical Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in the United States (2020–2060) Alzheimers Dement.. 2021;17(12):1966-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Association of race and ethnicity with incidence of dementia among older adults. JAMA.. 2022;327(15):1488-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Annual incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in the United States projected to the years 2000 through 2050. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord.. 2001;5(4):169-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- Race, Ethnicity, and Alzheimer’s. Chicago (IL): Alzheimer’s Association; 2020. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://aaic.alz.org/downloads2020/2020_Race_and_Ethnicity_Fact_Sheet.pdf

- Cognitive performance and informant reports in the diagnosis of cognitive impairment and dementia in African Americans and whites. Alzheimer’s Dement.. 2009;5(6):445-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occupational cognitive requirements and late-life cognitive aging. Neurol Educ.. 2016;86(15):386-92.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Health Retirement Study. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2023. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/news/data-announcements/hrs-hcap-2016-final-data-release-final-version-10

- Racial and ethnic disparities in the treatment of dementia among Medicare beneficiaries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci.. 2008;63(5):S328-33.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The carrot and the stick: Benefits and barriers in getting a diagnosis. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord.. 2002;16(4):213-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dementia in the black community: Risks and inequalities. Medical News Today. Brighton (UK): Healthline Media; 2021. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/dementia-in-the-black-community # other-inequalities

- 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Chicago (IL): Alzheimer’s Association; 2016. [Assessed 2024 May 28];12(4):459-509. Available from: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/dsi-tc/Complex%20Care/Alzheimers-Dementia-Roundtable.pdf

- Finding dementia care and local services. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Aging; [Assessed 2024 Jan 26]. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.gov/life-with-dementia/find-local-services

- The State of Long-Term Care Insurance: The Market, Challenges and Future Innovations. 2016. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://content.naic.org/site s/default/files/inline-files/cipr_current_study_160519_ltc_insurance_0.pdf

- Effective screening for Alzheimer’s disease among older African Americans. Clin Neuropsychol.. 2001;15(2):196-202. [Assessed 2024 May 28] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1076/clin.15.2.196.1892

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing cognitive ability in research: Use of MMSE with minority populations and elderly adults with low education levels. J Gerontol Nurs.. 2006;32(4):45-54.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racial differences in the recognition of cognitive dysfunction in older persons. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord.. 2012;26(1):44-49.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sooner or later? Issues in the early diagnosis of dementia in general practice: A qualitative study. Family Practice.. 2003;20(4):376-381.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longitudinal analysis of dementia diagnosis and specialty care among racially diverse Medicare beneficiaries. Alzheimers Dement.. 2019;15(11):1402-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Earlier onset of Alzheimer disease symptoms in Latino individuals compared with Anglo individuals. Arch Neurol.. 2005;62:774-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mild cognitive impairment and deficits in instrumental activities of daily living: A systematic review. Alzheimers Res Ther.. 2015;7(17):1-20.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The clinical course of advanced dementia. NEJM AI.. 2009;361(16):1529-38.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Contribution of psychosis and depression to behavioral disturbances in geropsychiatric inpatients with dementia. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol.. 1999;23(1):2-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evidence-based caregiver interventions in geriatric psychiatry. Psychiatr Clin North Am.. 2005;28(4):007-x.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep disturbances in caregivers of persons with dementia: Contributing factors and treatment implications. Sleep Med Rev.. 2007;11(2):143-53.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Chicago (IL): Alzheimer’s Association; 2024. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. 149 p. Available from: https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

- World Alzheimer report 2015: The global impact of dementia - an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015. [Assessed 2024 May 28] 87 p. Available from: https://www.alzint.org/u/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf

- Uncertainty and health literacy in dementia care. Tzu Chi Med J.. 2020;32(1):14.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medicare Detection of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement.. 2012;9(2):141-150.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Chicago (IL): Alzheimer’s Association; 2019. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://www.alz.org/media/documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-2019-r.pdf

- Dementia. Rochester (MN): Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; 2024. [Assessed 2024 May 28]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dementia/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20352019

- Alzheimer’s disease: Advances in drug development. J Alzheimers Dis.. 2018;65(1):3-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]