Translate this page into:

Intimate Partner Violence Among Adolescent Latina Mothers and Their Reproductive Outcomes: A Systematic Review

✉Corresponding author email: deepa.0424@gmail.com

Abstract

Objective:

Approximately 1 in 3 women worldwide has experienced intimate partner violence (IPV), with the region of the North, Central, and South Americas reporting a prevalence of 29.8%. The health impact of IPV on women's reproductive outcomes has been well-documented, but the intersection of IPV and reproductive outcomes in the adolescent population in Latin America has not been explored. The purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize the existing literature on reproductive outcomes associated with IPV in adolescent mothers in Latin America.

Methods:

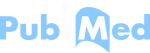

A systematic review of the literature using the PubMed database was conducted using a search term including key phrases pertaining to our topics of interest: Latin America, adolescent mothers, IPV, and reproductive outcomes. Articles published between 2010-2020 exploring at least two of the four major topics were included in our review. Articles were divided according to relevance to four categories: (1) Pregnancy and motherhood in Latina teens, (2) IPV in Latin America, (3) Reproductive outcomes associated with IPV, and (4) IPV among teen Latina mothers and their reproductive outcomes. PRISMA reporting guidelines were utilized, and flowcharts were created to demonstrate the study findings.

Results:

Of 288 initial articles, 0 articles explored the intersection of IPV and reproductive outcomes, specifically in teenage Latinas. However, 9, 16, and 22 were found to match the first three categories listed in the methods section. IPV was associated with adverse reproductive outcomes, both directly and indirectly, such as unintended pregnancy and preterm birth. Our results also showed that adolescent Latina women were at a significantly higher risk of both pregnancy and IPV than most women in other age groups globally.

Conclusion and Implications for Translation:

IPV represents a significant threat to the health of Latina women as well as their reproductive functions. Although Latinas represent an important proportion of the global adolescent population, current literature is scarce, and more research on the impact of IPV on adolescent Latinas is warranted.

Keywords

Intimate Partner Violence

Adolescent

Reproductive Outcomes

Latina

Introduction

Background

Approximately 1 in 3 women worldwide has experienced intimate partner violence (IPV), according to the World Health Organization (WHO).1 This percentage is even greater in developing parts of the world, with the region of the North, Central, and South Americas reporting a prevalence of 29.8%. This violence starts at a young age, with about 25% prevalence among women aged 15 to 19 years. IPV, which includes sexual violence, can lead to a number of physical and mental health problems, including unintended pregnancy, mental health issues, sexually transmitted diseases like HIV and syphilis, and substance abuse disorders, all of which can affect maternal and fetal health during pregnancy.1,2 Rising rates of IPV among adolescents are indicative that little is being done to address this issue.1

Objective

The purpose of this systematic review is to synthesize the existing literature on reproductive outcomes associated with IPV in adolescent mothers in Latin America.

Pregnancy and Motherhood among Adolescent Latinas

According to a 2015 United Nations (UN) publication on global fertility patterns, the birth rate (2010-2015) for Central American women ages 15 to 19 was 69 births per 1,000 women, with marked variation across the region.3 The birth rate for South American women ages 15 to 19 was 66 births per 1,000 women, with some countries like the Dominican Republic having adolescent birth rates of over 100 births per 1,000 women.3 By comparison, the global birth rate for women ages 15 to 19 within the same study period was 46 births per 1,000 women.3 This means that Latina adolescents have about a 50% greater likelihood of becoming pregnant compared to their global counterparts. Latin America and the Caribbean had a total fertility of 2.2 children per woman from 2010-2015. By comparison, high-income countries had a total fertility rate of 1.7 children per woman, and low- income countries had a fertility rate of 4.9 children per woman. However, the declining total fertility rates in low-income regions mean that the average age at childbearing has been decreasing as well.4

Globally, pregnancy and childbirth complications are the leading causes of death in women ages 15 to 19, though the risk of maternal mortality decreases with age in adolescents and young mothers.5 Nearly 20,000 girls in developing countries under the age of 18 give birth every day. Approximately 200 girls in the same age group die every day as a result of early pregnancy. For mothers under the age of 15 in low- and middle-income countries, the risk of maternal death is double that of older women.3 Similarly, infants born to mothers under 20 years old are 50% more likely to die than those born to mothers 20–29 years old.5 According to a 2017 report by Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)/WHO, the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF), and the UN Population Fund (UNFPA), 15% of all pregnancies in the Latin American region occur in women under the age of 20, and, though data on this age group is limited, UNFPA estimates that 2% of women in this region had their first delivery before the age of 15.5 It estimates that in 2012, 1,887 young women in the region ages 15 to 24 died as a result of conditions arising during pregnancy, childbirth, and the early postpartum period.5 The trends of adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with adolescent pregnancy remain true for developed nations as well. In a retrospective cohort study of 3,886,364 nulliparous pregnant women, all teenage groups (ages 10 to 15, 16 to 17, 17 to 18, and 18 to 19) were associated with increased risks for pre-term delivery, low birth weight and neonatal mortality, regardless of important known confounders such as socioeconomic status.1,6

IPV in Latin America

A 2012 report produced by PAHO, in collaboration with the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), derived data from 12 Latin American and Caribbean countries to give an account of intimate partner and sexual violence against women in the region. The main findings include 1) women in all twelve countries reported “ever experiencing physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner, ranging from 17.0% in the Dominican Republic 2007 to slightly more than half (53.3%) in Bolivia 2003”; 2) IPV can range from occasional moderate violent acts to chronic severe abuse. Emotional abuse by a partner in the last twelve months was highly prevalent, with percentages ranging from 13.7% of women in Honduras (2005/6) to 32.3% in Bolivia (2008); 3) physically abusive partners were also more likely to be emotionally abusive; and 4) IPV often has serious health consequences, both mentally and physically, including adverse reproductive health outcomes.7 The study also found that the social environments in many Latin American countries were conducive to gender inequality and the perpetuation of IPV in women.

From the study, PAHO and the CDC concluded that the reported prevalence of physical or sexual IPV ever generally tended to increase with women's age. However, in regard to physical or sexual IPV in the last 12 months, younger women reported violence at higher rates than older women, with women ages 15-19 reporting the highest prevalence with the exceptions of the Dominican Republic 2007 and Peru 2007/8 (prevalence was highest among the second youngest group of women, aged 20-24).7 In most of the surveys analyzed, younger age (15-19 years old and 20-29 years old) was associated with two to three times the level of partner violence in the past 12 months compared with women aged 40-49.7

In a study analyzing data from 19 countries, two of the three countries with the highest prevalence of physical IPV during pregnancy are Latin American countries (Colombia 2000: 10.6% and Nicaragua 1998: 11.1%).7,8 The findings from this study suggest that the prevalence of IPV during pregnancy remains fairly constant in all age groups between 15 and 35 and then declines slightly after the age of 35 in Latin American countries.

Reproductive Outcomes of IPV

A report by WHO found that the lifetime prevalence of physical and/or sexual IPV among women in the Western Hemisphere who had ever had a partner was 29.8%; in women ages 15 to 19, this rate was slightly lower (24.9%) but still relatively high.1 Among the health outcomes discussed in the report was incident HIV infection, incident sexually transmitted infections (STIs), induced abortion, low birth weight, premature birth, growth restriction in utero and/or small for gestational age, alcohol use, depression and suicide, injuries, and death from homicide. This data is also supported by the PAHO/ CDC report, which shows that unintended pregnancy, pregnancy loss, ‘problems’ during pregnancy, and physical violence during pregnancy all, in general, increased with partner violence.7 Findings from the 2008 Bolivia survey showed that 4% of women who reported physical or sexual partner violence in the past 12 months said that they had become pregnant as a result, and “8% said they experienced a ‘problem’ during pregnancy as a result. Among women who reported physical or sexual partner violence ever, 3.3% in Bolivia 2003 and 1.7% in Colombia 2005 reported losing a pregnancy as a result.” A review of seventy-five studies on health and IPV found that in both developing and developed nations, gynecological symptoms (most commonly bleeding after sexual intercourse during times other than menstruation, but also including abnormal vaginal discharge, pain or burning during urination, and pain during intercourse) were reported to be associated with a history of IPV by women.9 Women with a history of IPV are more likely to have abnormal Pap smear results, sexually transmitted infections, and higher rates of cervical cancer.10

The WHO's report also mentions other health outcomes that have been linked to IPV but are not discussed in the report, such as adolescent pregnancy, unintended pregnancy, miscarriage, stillbirth, intrauterine hemorrhage, gastrointestinal problems, chronic pain, anxiety, and PTSD, as well as non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases.1

Unintended Pregnancy

A study on global unintended pregnancy rates found that in 2008, 58% of all pregnancies in the Latin American and Caribbean region were unintended.10 This resulted in 22% of pregnancies ending in abortion and 8% of pregnancies ending in miscarriage.10 Another analysis of data on 87,087 women showed that nearly 50% (46.8%) of women had unintended pregnancies. They found a positive correlation between unwanted pregnancy and preterm delivery; women who were ambivalent toward their pregnancies had significantly increased odds of delivering a low-birth-weight infant.11 Of the 38 million sexually active adolescent girls ages 15 to 19 who live in developing regions of the world and do not want a child in the next two years, 23 million (about 60%) do not have access to modern contraceptives and are, therefore, at risk for unintended pregnancy.5

Abortion

Of all the world regions, the highest annual rate of abortion in 2010–2014 was in the Caribbean (59 per 1,000 women of reproductive age), followed by South America (48 per 1,000 women). This is about three-fold the comparative number from North America (17 per 1,000 women) and Western and Northern Europe (16 and 18 per 1,000 women, respectively).12 Each year, an estimated 16 million girls ages 15 to 19 and 2 million girls under the age of 15 become pregnant. Of these, approximately 5.6 million (35%) seek abortions. Abortion is associated with several adverse health outcomes, including emotional trauma in safe abortions and physical harm in unsafe abortions. Emotionally, the decision to terminate a pregnancy can lead to depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and higher rates of stress. Adolescents are especially susceptible to these emotional outcomes. Physically, abortions (particularly unsafe abortions) can result in infertility, consequences of internal organ injury (urinary and stool incontinence from vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulas), bowel resections, and death from hemorrhage, infection, sepsis, genital trauma, and necrotic bowel.13

Pregnancy Loss

Most of the existing data regarding women's and maternal health focus on live birth or infant death following a live birth; the literature surrounding miscarriages and pregnancy loss is very limited. The information becomes even scarcer when researched in association with adolescence, IPV, or both. Some of the reviewed sources grouped miscarriage with “severe injuries as a result of IPV,” making it comparable to sprains or broken teeth, while others did not address it at all. A study conducted on 269,273 women from six low-middle income countries from 2010 to 2013 found that in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America (reviewed as one category in this study), 11.9% of women ages 15-19 reported pregnancy loss in their last gestation compared to only 6.4% of women ages 20-24, indicating that adolescents are nearly twice as likely to experience pregnancy loss compared to young women in their twenties.4 Another study states that of the estimated 208 million pregnancies occurring in 2008, 185 million (about 90%) took place in the developing world, 17 million of which occurred in Latin America; of the approximately 86 million unintended pregnancies globally, 11 million resulted in miscarriages (about 13%). In Latin America, 8% of all births were unintended and resulted in miscarriage, compared to 5% globally.11

In a cross-sectional study on 2,562 Cameroonian women, researchers found that those exposed to spousal violence were 50% more likely to experience at least one episode of fetal loss than women not exposed to abuse. Furthermore, recurrent fetal mortality was associated with all forms of spousal violence (physical, emotional, and sexual), but emotional violence had the strongest association.14 A cross-sectional study of 1,897 women in Guatemala found that 16% of the sample had experienced verbal IPV, 10% had experienced physical IPV, and 3% had experienced sexual IPV, with adolescent women reporting higher rates of IPV than women over the age of 30. Ten percent of the women in the sample had experienced pregnancy loss. After adjusting for commonly confounding factors, physical or sexual IPV in the last 12 months was significantly associated with miscarriage.15 Elimination of exposure to IPV in five Latin American countries of Honduras, Guatemala, Dominican Republic, Peru, and Colombia was associated with 167,743 fewer pregnancy terminations.16 It is clear from the literature that adolescent women, women who have unintended pregnancies, and women who have experienced IPV (especially during pregnancy) are more likely to experience pregnancy loss. All reviewed studies addressing IPV acknowledge the potential association of fetal loss with IPV, but the literature remains insufficient for adolescent mothers.

Methods

Study Variables

A PubMed database search was conducted using a search term based on the following key ideas/phrases: intimate partner violence, adolescent mothers in Latin America, and reproductive outcomes of intimate partner violence. Articles published between 2010-2020 exploring at least two of the four major topics were included in our review. Exclusion criteria included non-Latin American populations, adult populations, not recently published, and not available in English. Articles were divided according to relevance to four categories: (1) Pregnancy and motherhood in Latina teens, (2) IPV in Latin America, (3) Reproductive outcomes associated with IPV, and (4) IPV among teen Latina mothers and their reproductive outcomes.

Search Strategy

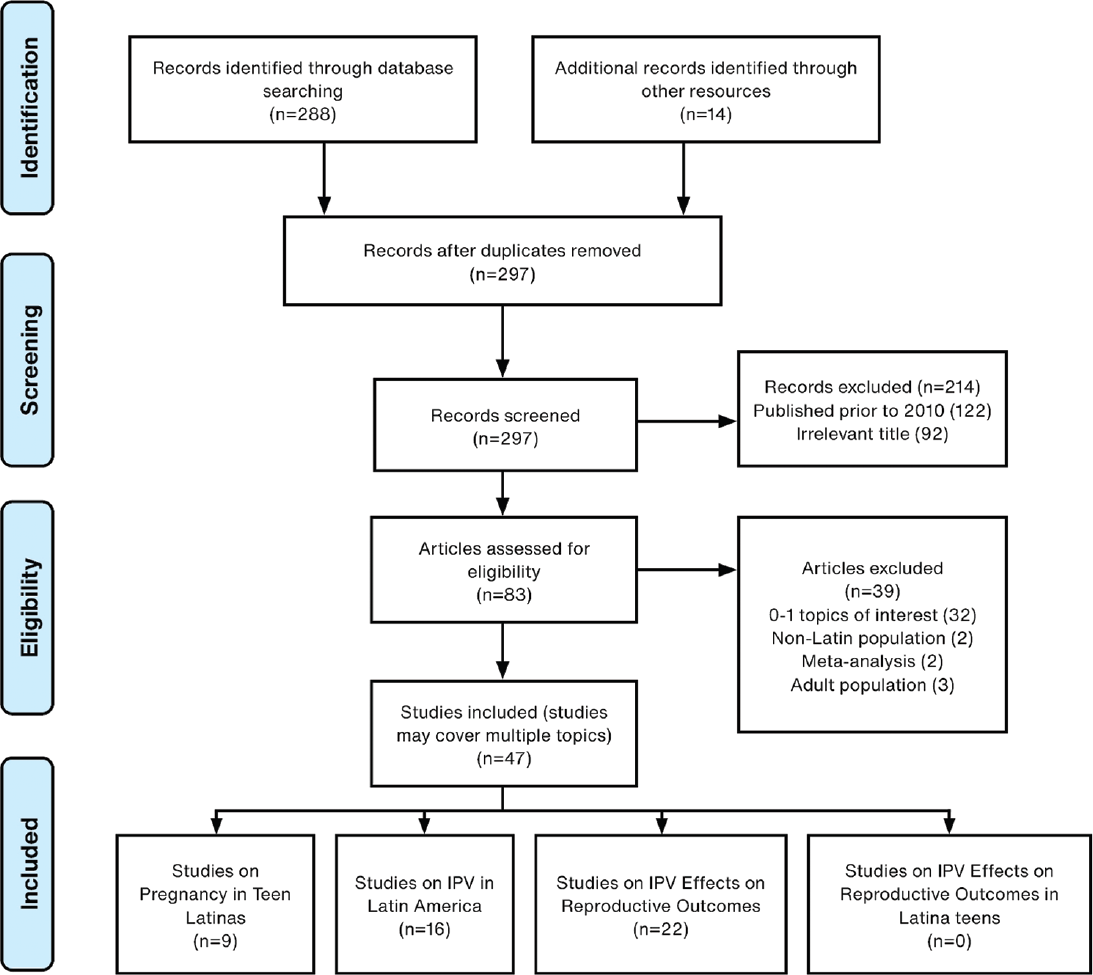

A search term was created to encompass the four major topics of interest. All results were screened by two investigators. Articles encompassing at least two topics of interest were queried for further review. A third investigator was available to analyze articles under question by the primary two investigators. Articles that were considered more relevant to our topic were ones that discuss Latin America or Latinas as a whole rather than individual countries or subsects of people, the prevalence of IPV, overall health/reproductive health in Latinas and adolescents, adolescent motherhood, or the effects of IPV on overall health/reproductive outcomes. We considered several possible reproductive outcomes of IPV: unintended pregnancy, pregnancy loss, abortion, HIV, premature delivery, vaginal bleeding, low birth weight, and infant death.

Results

Main Variable Results

Our search and inclusion strategy is demonstrated in Figure 1. Searching the search term, as seen in Figure 2, produced 288 results, 166 of which were published after 2010 and underwent extensive review. No articles in our systematic review discussed the intersection of IPV and reproductive outcomes in Latina adolescents; therefore, we broke down our findings into three categories (pregnancy and motherhood in adolescent Latinas, IPV in Latin America, and reproductive outcomes associated with IPV) and discussed ramifications for our complete topic of interest. Our review yielded 9, 16, and 22 applicable articles per category, respectively (Table 1A, 1B, 1C). The majority of the published cohort studies were completed in Brazil or the United States. Many studies were excluded due to discussing childhood abuse rather than IPV, discussing IPV in an adult population, or including African American, Middle Eastern, or other non-Latin populations.

- Search strategy utilized for obtaining studies for this review

- Search terms

| Author | Year | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Uysal et al. | 2020 | "At Least I Didn't Get Raped": A Qualitative Exploration of IPV and Reproductive Coercion among Adolescent Girls Seeking Family Planning in Mexico |

| Miura et al. | 2020 | Adolescence, pregnancy and domestic violence: social conditions and life projects |

| Ribeiro et al. | 2020 | Childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in pregnant adolescents in Southern Brazil |

| Udo et al. | 2016 | Intimate Partner Victimization and Health Risk Behaviors Among Pregnant Adolescents |

| Restrepo Martínez et al. | 2017 | Sexual Abuse and Neglect Situations as Risk Factors for Adolescent Pregnancy |

| Morón-Duarte et al. | 2014 | Risk factors for adolescent pregnancy in Bogotá, Colombia, 2010: a case-control study |

| United Nations | 2015 | World Fertility Patterns 2015 |

| Althabe et al. | 2015 | Adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: The Global Network's Maternal Newborn Health Registry study |

| United Nations | 2017 | Accelerating progress toward the reduction of adolescent pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean |

| Author | Year | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Coll et al. | 2020 | Intimate partner violence in 46 low-income and middle-income countries: an appraisal of the most vulnerable groups of women using national health surveys |

| Miura et al. | 2020 | Adolescence, pregnancy and domestic violence: social conditions and life projects |

| Ribeiro et al. | 2020 | Childhood trauma and depressive symptoms in pregnant adolescents in Southern Brazil |

| Sandoval et al. | 2020 | Mortality risk among women exposed to violence in Brazil: a population-based exploratory analysis |

| Khan et al. | 2019 | Multicountry analysis of pregnancy termination and intimate partner violence in Latin America using Demographic and Health Survey data |

| Mitro et al. | 2019 | Childhood abuse, intimate partner violence, and placental abruption among Peruvian women |

| Ludermir et al. | 2017 | Previous experience of family violence and intimate partner violence in pregnancy |

| Ceccon et al. | 2015 | HIV and violence against women: study in a municipality with high prevalence of Aids in the South of Brazil |

| Silva et al. | 2015 | Incidence and risk factors for intimate partner violence during the postpartum period |

| Jackson et al. | 2015 | Intimate partner violence before and during pregnancy: related demographic and psychosocial factors and postpartum depressive symptoms among Mexican American women |

| Ribeiro et al. | 2014 | Psychological violence against pregnant women in a prenatal care cohort: rates and associated factors in São Luís, Brazil |

| Azevêdo et al. | 2013 | Intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy: prevalence and associated factors |

| Devries et al. | 2010 | Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries |

| Rico et al. | 2011 | Associations between maternal experiences of intimate partner violence and child nutrition and mortality: findings from Demographic and Health Surveys in Egypt, Honduras, Kenya, Malawi and Rwanda |

| Bott et al. | 2012 | Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries. Pan American Health Organization |

| WHO | 2013 | Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence |

| Author | Year | Name |

|---|---|---|

| Khan et al. | 2019 | Multicountry analysis of pregnancy termination and intimate partner violence in Latin America using Demographic and Health Survey data |

| Thomas et al. | 2019 | Associations between intimate partner violence profiles and mental health among low-income, urban pregnant adolescents |

| Silva et al. | 2019 | Mental health of children exposed to intimate partner violence against their mother: A longitudinal study from Brazil |

| Mitro et al. | 2019 | Childhood abuse, intimate partner violence, and placental abruption among Peruvian women |

| Ferraro et al. | 2017 | The specific and combined role of domestic violence and mental health disorders during pregnancy on new-born health |

| Tabb et al. | 2018 | Intimate Partner Violence Is Associated with Suicidality Among Low-Income Postpartum Women |

| Ludermir et al. | 2017 | Previous experience of family violence and intimate partner violence in pregnancy |

| Gelaye et al. | 2016 | Childhood Abuse, Intimate Partner Violence and Risk of Migraine Among Pregnant Women: An Epidemiologic Study |

| Sanchez et al. | 2016 | Intimate Partner Violence Is Associated with Stress-Related Sleep Disturbance and Poor Sleep Quality during Early Pregnancy |

| Cha et al. | 2017 | Partner violence victimization and unintended pregnancy in Latina and Asian American women: Analysis using structural equation modeling |

| Isaksson et al. | 2015 | High maternal cortisol levels during pregnancy are associated with more psychiatric symptoms in offspring at age of nine - A prospective study from Nicaragua |

| Fonseca-Machado et al. | 2015 | Under the shadow of maternity: pregnancy, suicidal ideation, and intimate partner violence |

| Fonseca-Machado et al. | 2015 | Depressive disorder in pregnant Latin women: does intimate partner violence matter? |

| Gibson et al. | 2015 | Intimate partner violence, power, and equity among adolescent parents: relation to child outcomes and parenting |

| Rodrigues et al. | 2014 | Intimate partner violence against pregnant women: study about the repercussions on the obstetric and neonatal results |

| Miranda et al. | 2012 | Prevalence and correlates of preterm labor among young parturient women attending public hospitals in Brazil |

| Johri et al. | 2011 | Increased risk of miscarriage among women experiencing physical or sexual intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Guatemala City, Guatemala: cross-sectional study |

| Ishida et al. | 2010 | Exploring the associations between intimate partner violence and women's mental health: evidence from a population-based study in Paraguay |

| Moraes et al. | 2010 | Physical intimate partner violence during gestation as a risk factor for low quality of prenatal care |

| WHO | 2013 | Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevlanece and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence |

| Dilon et al. | 2013 | Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: A review of the literature |

| Mogos et al. | 2016 | The feto-maternal health cost of intimate partner violence among delivery-related discharges in the United States, 2002-2009 |

Discussion

The focus of this research was to gauge the relationship between IPV and reproductive outcomes in adolescent Latina mothers. The literature shows that (1) IPV is associated with worse reproductive outcomes, both directly and indirectly, such as unintended pregnancy and preterm birth; (2) Adolescent mothers are more likely to suffer from complications during pregnancy and childbirth; (3) Adolescent women are more at risk for IPV, including IPV during pregnancy; (4) Latin American countries have the second highest prevalence of IPV of the WHO global regions; (5) Latin American countries have the second highest rate of adolescent pregnancy in the world. However, none of the topical studies directly ties IPV to reproductive outcomes in adolescent mothers in Latin America. Publications that have any semblance of each of these topics fail to cover a least one of them in detail, usually age or specific reproductive outcomes.

While all the literature regarding adolescent Latina women and violence against Latina women is helpful, this simply is not enough. The amount, relevance, and thoroughness of data collected vary greatly by country. There is a clear scarcity of information that is (1) current and relevant; (2) thorough; (3) available for all Latin American countries; and (4) readily accessible. Although several articles provided information on IPV based on characteristics or demographics, none of the literature covers adolescent women in detail. There is little to no information on adolescent Latina mothers regarding partner violence. It is for that reason that this study, as well as future studies, are absolutely warranted.

Recommendation for Further Studies

Globally, IPV is an issue that, despite its awful outcomes, is largely under-reported and often ignored. This violence disproportionately affects young Latinas who are already at heightened risk of unintended adolescent pregnancy and numerous health issues that arise thereof. Though the problems present themselves in individuals, the greater issues exist at the legislative and societal levels. Current policies in Latin America create environments that encourage unsafe abortion and overlook abuse. Though we do not have any direct proposals, we have identified several topics that we believe should be addressed: (1) the unmet need for contraception in Latin America; (2) the lack of clinical screening for abuse during pregnancy; (3) the lack of support for abused women; (4) the policies which lead to unsafe abortions; (5) the lack of sexual health education; and (6) the policies which pardon violent partners and force women to endure partner violence. Only once these topics have been addressed will we see an improvement in reproductive outcomes of IPV in adolescent Latina mothers.

Conclusion and Implications for Translation

Healthcare providers, case workers and policy makers should target educational intervention and provide assistance to women from vulnerable populations in Latin America to achieve conducive reproductive outcomes and maintain good health for the adolescents. Various media such as television and internet could be used to promulgate the importance of and means to access contraception, proper medical care, support for abused women, sexual and reproductive health education etc.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial Disclosure:

Nothing to declare.

Ethics Approval:

Not applicable.

Disclaimer:

None.

Acknowledgments:

None.

Funding:

Research funding support was provided by the US Department of Health and Human Services and Health Resources and Services Administration for Baylor College of Medicine Center of Excellence in Health Equity, Training, and Research (Grant No: D34HP31024).

References

- Global and Regional Estimates of Violence Against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. World Health Organization; Published October 20, 2013 (accessed )

- The feto-maternal health cost of intimate partner violence among delivery-related discharges in the United States, 2002-2009. J Interpers Violence. 2016;31(3):444-464.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Fertility Patterns 2015 2015

- Adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes in adolescent pregnancies: the global network's maternal newborn health registry study. Reprod Health. 2015;12(Suppl 2):1-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accelerating Progress Toward the Reduction of Adolescent Pregnancy in Latin America and the Caribbean 2017

- Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: a large population based retrospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(2):368-373.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries. Pan American Health Organization; 2012.

- Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: analysis of prevalence data from 19 countries. Reprod Health Matters. 2010;18(36):158-170.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental and physical health and intimate partner violence against women: a review of the literature. Int J Family Med. 2013;2013:313909.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unintended pregnancy: worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Stud Fam Plann. 2010;41(4):241-250.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pregnancy intention and its relationship to birth and maternal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(3):678-696.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute; Retrieved June 11, 2018

- Unsafe abortion: unnecessary maternal mortality. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(2):122-126.

- [Google Scholar]

- Spousal violence and potentially preventable single and recurrent spontaneous fetal loss in an African setting: cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2009;373(9660):318-324.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increased risk of miscarriage among women experiencing physical or sexual intimate partner violence during pregnancy in Guatemala City, Guatemala: cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011;11(1):49.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multicountry analysis of pregnancy termination and intimate partner violence in Latin America using Demographic and Health Survey data. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019;146(3):296-301.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]