Translate this page into:

Hypertension in Saudi Arabia: Assessing Life Style and Attitudes

✉Corresponding author email: belbashir@moh.gov.sa or bushrael@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background:

The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet lowers blood pressure (BP) effectively. There is evidence that strongly supports the concept that lifestyle modification has a powerful effect on BP. The DASH diet includes increased physical activity, reduced salt intake, weight loss, increased potassium intake, and an overall healthy dietary pattern. This study assesses the knowledge and attitudes of Saudis in Riyadh City towards lifestyle and hypertension.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was designed using a questionnaire-based assessment tool, which included sociodemographic data, knowledge and lifestyle attitudes toward hypertension, such as dietary factors, stress, smoking, physical activities, and diet-related diseases (including obesity and diabetes mellitus). Statistical analyses to examine the perceived association between lifestyle factors and hypertension risks included frequency distribution, percentages, and chi-square tests of significance.

Results:

Out of 934 total participants, 13.6% were hypertensive; 84.4% and 60.2% of participants believed eating salty food and fatty food, respectively, were risk factors for hypertension. Almost 66.0% of participants considered stress as a risk factor for the development of hypertension, whereas 77.0% considered smoking as a risk factor. The data showed that 87.5% considered obesity as a risk factor, and 73.8% considered reducing weight as a preventive measure for hypertension. Also, 68.8% believed that physical inactivity was a risk factor for hypertension. Data showed that 16.6 % ate vegetables and 23.1% ate fruits as recommended, whereas 18.8% and 18.4%, respectively, rarely ate vegetables and fruits. About 12.1% smoked and 19.7% exercised regularly, whereas 15.6% did not exercise at all. Traffic and examination were reported as stress factors by younger participants.

Conclusion and Implications for Translation:

The knowledge of the relationship between hypertension risk factors and eating salty or fatty food was high. In contrast, knowledge of not eating vegetables and fruits as a risk factor for the development of hypertension was very low among the Saudis.

Keywords

DASH

Hypertension

Life Style

Knowledge

Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Hypertension in adults is defined as blood pressure (BP) higher than 130 over 80 millimeters of mercury (mmHg),according to the American HeartAssociation.1 Hypertension is becoming a global epidemic, with around 1.13 billion people being affected.2 High BP typically does not have symptoms. However, there are many causes and risk factors. Modifiable risk factors include unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, tobacco and alcohol intake, and being overweight, or obese. Non-modifiable risk factors include a family history of hypertension, age over 65 years, and co-existing diseases such as diabetes, depression, or renal disease.2 In fact, sedentary lifestyles and increased body weight are estimated to increase the number of persons with hypertension by 15–20%, by 2025.3 The World Health Organization (WHO) suggested that the growth of the processed food industry had impacted the amount of salt in diets worldwide, which plays an essential role in hypertension.4 It has been argued that increasing awareness, prevention, and control programs for hypertension in the community could help residents enjoy and maintain a healthy lifestyle.5 A prospective urban rural epidemiology study with participants from 52 urban and 35 rural communities from four countries in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, detected that about 33% participants, had hypertension and about 49% of these hypertensive participants were aware of their diagnosis.6 The WHO's BP control guidelines recommend that patients with hypertension should engage in at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise throughout each week.7 If a patient's systolic BP is 130-140 mm Hg, lifestyle modifications are recommended before resorting to medication.8 Age, educational level, employment status, and family history are not significantly associated with knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding hypertension.5 In Saudi Arabia, the hypertension prevalence was shown to be 6% in males, 4.2% in females, and 4.9% in all subjects in a cross- sectional survey-based analysis of 1,019 participants. Obesity was identified as the highest risk factor for hypertension and class I obese (30–34.9kg/m2) patients had a 3.5 times higher risk of hypertension compared to the non-obese group.9 A 2017 cross-sectional study by medical students from Qassim University in Saudi Arabia reported an association of hypertension with gender, body mass index (BMI), physical inactivity, and family history of diabetes and hypertension.10 A national survey conducted in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) including 10,735 participants found that around 15.2% and 40.6% of Saudis were hypertensive or borderline hypertensive, respectively. Age, obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia were considered to be the major risk factors for hypertension among men.11,12 Lifestyle modifications are the best way to address high BP.13 Lifestyle advice should be given to the people diagnosed with or suspected with hypertension, along with asking their diet and exercise patterns and recommending them healthy diet and regular exercise.13 A Spanish cohort study analysed the role of lifestyle behavior on the risk of hypertension and reported that a healthy-lifestyle score, including six simple healthy habits was longitudinally and linearly associated with a substantially reduced risk of hypertension.14

Significant positive correlations between hypertension and unhealthy diet, especially salty and fatty food, physical inactivity and stress had been or were observed. However, there is no published data on the lifestyle knowledge and attitudes of Saudi people concerning hypertension. The aim of this study was to assess the knowledge and attitudes of Saudi people towards the association of hypertension with lifestyle.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study that was carried out at multiple centers and sites in Riyadh City, in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Subjects included were Saudis residing in Riyadh City for more than three years, aged above 12 years, from both sexes. Data were collected using a structured interviewer- guided questionnaire with answers; a cover note was provided explaining the objectives of this study. The respondents were asked to participate, and were free to withdraw from the study at any point. Documents were provided illustrating the exercise and recommended dietary allowance (RDA) especially the vegetables, salt, fruits and fat that were introduced to the subjects before the interview15 in order to know the RDA for specific food groups or food items. Collected data were entered and analysed using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp., Amonk, NY, USA). Statistical analyses to examine perceived association between lifestyle factors and hypertension risks included numbers and percentages for each category as well as Chi-square tests of significance. To evaluate the association between lifestyle and perceived risk of hypertension, dietary knowledge and habits, smoking, stress, family relationships, physical inactivity, obesity, and diabetes mellitus were considered as independent variables. Perceived risk of hypertension was considered as the dependent variable. Furthermore, stress was analyzed as a dependent variable, with age, sex, marital status, traffic, and examination as independent variables. If p<0.05, the differences were considered to be significant. Ethical approval was sought and approved from King Fahad Medical City, KSA, to conduct the research (IRB Registration Number with KACST, KSA was H-01-R-012. The IRB Registration Number with OHRPL NIH, USA was IRB00010471.

Results

Sociodemographics Characteristics of Study Participants

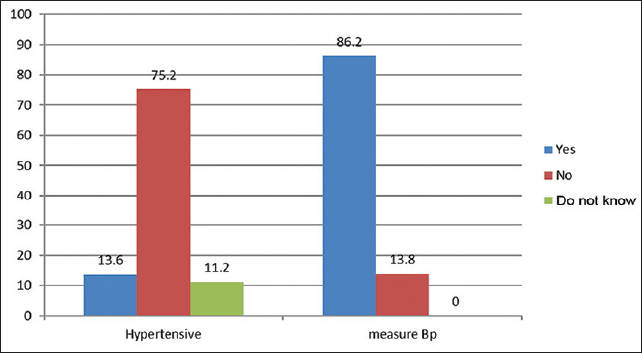

One thousand (n=1,000) subjects initially volunteered to participate in this study, and 93.4% (n= 934) subjects returned the questionnaire. Among the participants, 49.0% were males and 51.0% were females with age above 12 years. Among 934 subjects, 64.1% were married, 35.0% were single and 0.9% were divorced or widowed. The employment status of the participants was as follows: 24.5% were students; 47.1% were employed; and 17.6% were housewives. The education levels of the subjects were as follows: 58.5% were postgraduates; 25.4% were secondary educated; and 21.1% were intermediate or below (data not shown here). Of the total subjects interviewed,86.2% measured their BP and among them, 13.6% were hypertensive, and 75.2% were not hypertensive (Figure 1). Among the participants, 59% used to measure their BP when advised by the medical staff (data not shown here).

- Prevalence of blood pressure and percentage of subjects who measured their blood pressure.

Dietary Risk Factors for Hypertension

About 84.4% and 60.2% of participants thought that eating salty food and fatty food respectively, were risk factors for the development of hypertension. Almost 43.5% and 48.2% of participants did not know that not eating vegetables and fruits can be a risk factor for the development of hypertension (Tables 1a and 1b).

| Knowledge | Yes % | No % | Don't know % | Chi Square |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating salty food is a risk factor | 84.4 | 5.4 | 10.3 | < 0.001 |

| Eating fatty food is a risk factor | 60.2 | 18.5 | 21.3 | < 0.001 |

| Not eating vegetables is a risk factor | 35.0 | 21.5 | 43.5 | < 0.001 |

| Not eating fruits is a risk factor | 20.9 | 30.9 | 48.2 | < 0.001 |

| Habits | Yes % | Usually % | Sometimes% | Rarely % | No Answer% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you eat salty food? | 30.9 | 19.5 | 33.1 | 13.0 | 3.5 |

| Do you eat fatty food? | 29.0 | 17.7 | 40.2 | 11.0 | 2.0 |

| Eat vegetables as recommended | 16.6 | 26.3 | 36.6 | 18.8 | 1.6 |

| Eat fruits as recommended | 23.1 | 20.4 | 35.8 | 18.4 | 2.2 |

Behavioral Risk Factors for Hypertension

Almost 77.0% of participants considered smoking, 66.0% considered stress, and 68.8% considered physical inactivity as a risk factor for hypertension (Table 2). However, only 12.1% smoke daily and 19.7% practiced exercise regularly (data not shown). In all, 87.5% understood that obesity is a risk factor for hypertension and 73.8% believed that reducing body weight is a preventative measure for the development of hypertension (Figure 2).

- Relation between hypertension and other diseases.

| Knowledge | Yes % | No % | Don't know% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking is a risk factor | 77.0 | 2.9 | 20.1 |

| Stress is a risk factor | 66.0 | 6.5 | 27.5 |

| Relative relations reduce risks | 60.1 | 6.1 | 33.8 |

| Laziness is a risk factor | 68.8 | 7.0 | 24.2 |

| Playing with a smart device | 15.1 | 65.8 | 19.1 |

Stress was more common in males than in females. Examination and traffic were causes of stress more in males than in females and the differences were statistically significant (p<0.05) (Table 3). There were no significant differences between single and married subjects concerning the prevalence of stress; however, it was significantly higher among divorces and widows 38.1% had stress due to work (data not shown). The occurrence of stress was higher among subjects aged 12-19 years and of age 51 years and above as compared to subjects aged 20-50 years. Among the employees, 38.1% had stress due to work (data not shown).

| Indicator | Numbers (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Males | Females | Total | P value |

| Number who are stressed | 41.0% (188) | 32.3% (307) | 36.4%(340) | <0.05 |

| Sources of stress | 11.2% (31) | 16.0% (49) | 13.7% (80) | >0.05 |

| Traffic | 18.4% (51) | 2.6% (8) | 10.1% (59) | <0.05 |

| Examination | 20.7% (57) | 2.3% (7) | 13.3% (64) | <0.05 |

Discussion

There are various complex aetiologies of hypertension including both genetic and behavioural factors. Dietary modifications that lower BP are reduced salt intake, weight loss, and increased potassium intake.16 In this study, 84.4% agreed that salty food is a risk factor for hypertension, 87.5% agreed that obesity is a risk factor for BP, and 73.8% considered reducing weight is a preventive measure against BP (Table 1; Figure 2). High salt intake may predispose children to develop hypertension. The worldwide reduction in salt intake would, therefore, result in a major improvement in public health in terms of hypertension.17

Dietary approaches to reduce hypertension such as eating fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nuts, were associated with decreased BP.18,19 One study reported that a vegetarian/vegan group had significantly lower hypertension compared to non- vegetarians.20 Our study also suggested that 35.0% believed that hypertension may result from not eating vegetables. Another study suggested that a plant-based diet is very important for preventing and treating hypertension.18

In uncomplicated hypertension, dietary changes serve as an initial treatment before drug therapy. Consuming food rich in potassium and calcium helps in reducing uncomplicated hypertension.2 In non- hypertensive individuals, dietary changes can lower BP and prevent hypertension.16 In this study, although 20.9% believed not eating fruits is a risk factor for hypertension, only 23.1% and 20.4% took fruits daily or usually, as recommended (Table 1). The intake of fruits, as good sources of potassium, facilitates the reduction of high BP. Increased potassium intake and consumption of food based on the “DASH diet” have emerged as an effective strategy in lowering BP.21

Also, psychological stress is proposed as a significant factor contributing to the development of hypertension. Global urbanization, daily stress at the workplace, and lack of social support lead to increased anxiety, uncertainty, and finally to chronic mental and emotional stress.22 About 66.0% of the subjects in this study believed that stress is a risk factor for hypertension. About 60.1% believed that relationships, especially with family and friends, increase social support and may reduce the risk of hypertension (Table 2).

Sympathetic activation initiating a cascade of pathophysiological reactions is considered as a primary link in the development of stress-induced arterial hypertension.23 In this study, almost 38.1% of the employees believed that their stress triggers at work (data not shown). A study revealed an increase in BP indicators during the working day and their normalization at the weekend, which is mainly because job stress almost completely disappears at weekends.24 Epidemiological and meta-analysis data indicate job stress as a risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events. Moreover, the β-blockers are being considered to treat patients with stress- induced hypertension.23,25

In this study, 87.5% answered obesity as a risk factor and 73.8% answered reducing weight as a preventive measure against hypertension (Figure 2). The foundation for a healthy BP consists of a healthy diet, adequate exercise, stress reduction, and a sufficient amount of potassium intake. Targeted weight-loss interventions in population subgroups might be more effective for the prevention of hypertension than a general-population approach.17 Our data showed that 68.8% think that physical inactivity, such as laziness, is a risk factor for BP development. Physical inactivity is one of the plausible mechanisms playing a key role in the development of hypertension in modern lifestyle conditions. Particularly the loss of connection between psychosocial strain and physical activity may underlie the deleterious effect of stress on cardiovascular and metabolic health.22

The prevalence of hypertension was significantly higher in passive smokers than in non-passive smokers.26 Active smoking is linked with hypertension. Smoking is a significant risk factor for hypertension and there are various strategies that can be used to promote smoking cessation. Physicians are in an excellent position to help their patients stop smoking.17 Cigarette smoking acutely exerts a hypertensive effect, mainly through the stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system. Smoking affects arterial stiffness and wave reflection that might have greater detrimental effect on central BP. Hypertensive smokers are more likely to develop severe forms of hypertension, including malignant and renovascular hypertension, an effect likely due to an accelerated atherosclerosis.27 In this study, 77.0% answered that, smoking is a risk factor for hypertension and only 2.9% did not agree that smoking is a risk factor (Table 2). This study showed that 12.1% of the participants smoked on a daily basis, and 80.3% did not smoke at all, and others, smoke sometimes or rarely. The main limitation of this study was that it included participants who were only from Riyadh city.

Conclusions and Implications for Translations

The knowledge of Saudis regarding the relationship between consuming salty and fatty food, obesity, smoking, and stress as risk factors for hypertension was good. In contrast, the relation between being physically active, consuming vegetables and fruits as preventive measures against the development of BP were low. The attitudes concerning eating a healthy diet and being physically active did not coincide with their knowledge. The causes of stress were different, according to socioeconomic groups.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest:

The authors state that there are no conflicts of interest to report.

Financial Disclosure:

Nothing to declare.

Ethics Approval:

IRB Registration Number with KACST KSA (H-01-R-012); IRB Registration Number with OHRPLNIH, USA (IRB00010471); Approval Number Federal Wide Assurance NIH, USA (FWA00018774). Three of the authors had PHRP certificates were as follows: Bushra Elbashir Protecting Human Research Participants (PHRP) online date: 09/21/2019 Certificate No 2838378; Musab Al-Dakheel PHRP online date: 09/24/2019 Certificate No 2840735; Hamd Aldakheel PHRP online date: 09/24/2019 Certificate No 2840734.

Disclaimer:

None.

Acknowledgment:

We would like to thank our directorates, who allowed us to conduct this research. The authors also thank all participants in this study.

Funding/Support:

For the work done by the authors, there is no fund received from any agency or company at all.

References

- Age-stratified prevalence, treatment status, and associated factors of hypertension among US adults following application of the 2017 ACC/AHA guideline. Hypertens Res. 2019;42(10):1631-1643.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hypertension. Geneva: WHO; Published 2019. Updated 13.09.2019 (accessed )

- 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36(10):1953-2041.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Guideline Development Group for the Diagnosis and Pharmacological Treatment of Hypertension in Adults. Geneva: WHO; (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding hypertension among residents in a housing area in Selangor, Malaysia. Med Pharm Rep. 2019;92(2):145-152.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in four Middle East countries. J Hypertens. 2017;35(7):1457-1464.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An overview of current physical activity recommendations in primary care. Korean J Fam Med. 2019;40(3):135-142.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of hypertension and prehypertension and its associated cardioembolic risk factors; a population based cross-sectional study in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1-327.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of hypertension and its associated risk factors among medical students in Qassim University. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2018;29(5):1100-1108.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Hypertension Guidelines 2018. Saudi Hypertension Management Society; Published 2018 (accessed )

- Hypertension and its associated risk factors in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013: a national survey. Int J Hypertens. 2014;2014:564679.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2022.

- The role of lifestyle behaviour on the risk of hypertension in the SUN cohort: the hypertension preventive score. Prev Med. 2019;123:171-178.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause's Food and the Nutrition Care Process (14th). Saunders; 2016.

- Dietary approaches to prevent and treat hypertension: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension. 2006;47(2):296-308.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lifestyle modifications to prevent and control hypertension. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2016;10(5):237-263.

- [Google Scholar]

- A plant-based diet and hypertension. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2017;14(5):327-330.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fresh fruit consumption and major cardiovascular disease in China. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(14):1332-1343.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegetarian diets and cardiovascular risk factors in black members of the Adventist Health Study-2. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(3):537-545.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of sodium reduction and the DASH diet in relation to baseline blood pressure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(23):2841-2848.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological stress in pathogenesis of essential hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rev. 2016;12(3):203-214.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worksite hypertension as a model of stress-induced arterial hyper- tension. Ter Arkh. 2018;90(9):123-132.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Early diagnosis of stress-induced hypertension in young employees of state law enforcement agencies. Article in Russian. Klin Med (Mosk). 2017;95(1):45-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depression increases the risk of hypertension incidence: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Hypertens. 2012;30(5):842-851.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association between passive smoking and hypertension in Chinese non-smoking elderly women. Hypertens Res. 2017;40(4):399-404.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigarette smoking and hypertension. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(23):2518-2525.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]