Translate this page into:

Willingness to Become Deceased Organ Donors among Post-graduate Students in Selected Colleges in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal

✉Corresponding author email: pragya.paneru@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction:

Globally, there is a discrepancy between demand and availability of organs for transplantation. Transplantation is done from a living donor as well as a brain-dead/deceased donor. However, the World Health Organization (WHO) encourages deceased donor transplantation, since there is no risk to the donor. Although, the Transplant Act of Nepal 2016 opened the doors for deceased donor organ transplantation, the rate of transplantation from deceased donors is very low. Thus, this study assesses factors associated with willingness for deceased organ donation among post-graduate students of law, medicine, and mass communication streams.

Methods:

A total of 9 colleges, 3 from each specialty were selected via lottery method. The total sample size calculated was 440. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect the data. 170, 140 and 130 forms were distributed in law, medicine and mass communication respectively via convenient sampling. Multivariate analysis among the variables that had p-value <0.05 in bivariate analysis was carried out to find out the strongest predictors of willingness to be a deceased organ donor.

Results:

In all, 53.2% were willing to become deceased organ donors. Family permission having someone in family with chronic disease, having attended any conference or general talk on organ donation, knowing a live organ donor, and knowing that body will not be left disfigured after organ extraction were found to be the strongest predictors for willingness to be deceased organ donor. Lack of awareness was reported as the main barrier.

Conclusion:

There is a need for extensive awareness programs and new strategies to motivate individuals and family members for organ donation.

Keywords

Deceased Organ Donation

Willingness

Kathmandu

Nepal

Organ Transplantation

Living Donor

Deceased Donor

Introduction

Background of the study

Organ donation is when a person legally allows an organ of their own to be removed and transplanted to another person, either by consent while the donor is alive or with the assent of the next of kin if the donor is dead.1 Organ transplantation is the most preferred treatment modality for end-stage organ disease and organ failures.2 Technological advances in the past few decades have enhanced the feasibility of organ transplantation, which has pushed the demand for organs. Consequently, shortage of organs has become a global concern.3 The inadequate supply of cadaver organs is especially crucial for heart, lung and liver recipients, since these patients cannot be maintained for long on mechanical devices, unlike patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) who can be maintained on dialysis.4 For the success of the organ donation program, a positive public attitude toward organ donation and the consent by relatives for organ donation in the event of brain death are required.5 Although, organ donation is a personal issue, the process has medical, legal, ethical, organizational and social implications.6

According to the National Kidney Foundation, with the rise in cases of kidney disease and renal failure, there are at least 100,000 people on waiting lists for kidneys.7 Different approaches are taken to meet this demand, such as live donation and deceased organ donation.

In the previous ten years, about 49,000 people in the UK have waited for an organ transplant, and more than 6,000 of them, including 270 children, have passed away before receiving one.8 Transplantation became a successful global practice in the last 50 years. However, there are significant differences between countries in terms of the accessibility to appropriate transplantation as well as the extent of safety, quality and efficacy of organ donation and transplantation. Patient's unmet requirements and a paucity of transplants stimulate the trafficking of human organs for transplantation.9

The third WHO Global Consultation on Organ Donation and Transplantation advocates for self-sufficiency.10 Striving to achieve self-sufficiency optimizes the resources available within a country to meet demand for organ donation and transplantation.11 For example, within 13 years, Portugal reported over 100% increase in organ donation by training health professionals.10

In developed countries, there are about 25-30% cadaver organ donors whereas India has a 0.08 per million cadaver organ donation rate.12

Existing studies have shown wide knowledge and attitudes gaps about organ donation among the general public; these gaps are worsened by religious attitudes and superstitious beliefs that generating fear and mistrust about organ donation.13

Some studies have suggested that knowledge, attitudes and determinants concerning this issue are influenced by many factors, including gender, educational level, occupation, socio-demographic status, income level, culture and religion.13,15,16 Although people generally express favorable views toward organ donation, very few actually agree to donate before they die or agree to have family members' organs donated upon their deaths. The lack of organ donation is a major limiting factor in transplantation in most countries.16

In Nepal, it is estimated that about 3,000 people develop kidney failure every year, whereas the incidence of liver failure is 1,000 every year.17 Similarly, an estimated 30% of the diabetic population in Nepal might benefit from pancreas transplantation.18 In 2000, an Organ Transplant Act was passed to legalize transplantation with living donors who are close relatives to the recipients in Nepal.19 A successful kidney transplant from a live donor was performed in 2008 at the Tribhuwan University Teaching Hospital.20 The very first liver transplantation was performed at the Shahid Dharmabhakta National Transplant Center, Bhaktapur on December 7, 2016.21Likewise, kidney transplantation from a deceased donor works just as well as the kidney transplantation from a live healthy donor which was conducted on May 10, 2017.22 Recently in 2016, the Parliament of Nepal has brought about massive amendments to the old Organ Transplant Act of Nepal, opening doors for cadaveric organ donation and transplantation.23 According to news reports, in Kathmandu alone, road accidents leave around 1,000 people brain dead annually, whose organs, if procured, could save thousands of lives. If the newly amended legislation is implemented effectively, not only would this save lives for numerous Nepalese people, it would dissuade people from travelling to neighboring countries and paying much higher fees to receive organs. It would also help curb illegal buying and selling of organs as well as reduce gender bias in who receives the organs.18

However, there is a dearth of research regarding the willingness to donate organs and the factors influencing willingness to be a deceased organ donor. Today's post graduate students of medicine, law, and mass communication are tomorrow's professionals who can play an important role in influencing policy and implementation of programs related to organ donation.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to assess the willingness to be a deceased organ donor among these post-graduate students in Nepal, and to explore the association of their willingness with various facilitating or hindering factors. The results from this study will be useful for policy makers to plan strategies to increase the number of deceased organ donors in Nepal.

Objective of the study

The objective of this study was to assess the factors associated with willingness for cadaveric organ donation among the post-graduate students of various specialties, namely, Medicine, Law and Mass Communication.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in nine colleges; 3 from each specialty, selected via lottery method. The following specialties and colleges were selected for this study:

1. Medical colleges: Tribhuwan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH), National Academy of Medical sciences (NAMS) and Kathmandu University (KU);

2. Law colleges: National Law College (NaLC), Nepal Law campus (NLC) and Chakraborty Habi Law College; and

3. Mass communication colleges: Madan Bhandari Memorial College (MBM), Ratna Rajya Campus (RR) and Kantipur City College (KCC).

The study period was six months from 1st December, 2016 to 31st May, 2017. The study samples were selected conveniently. The sample size calculated was 440, after using 51.3% prevalence in one of the similar studies done in Turkey,24 with 10% non-response rate. The number of questionnaires distributed in medicine, law and mass communication was 140, 170 and 130 respectively.

A semi-structured self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data for the quantitative data collection. It had three parts: the first part (7 questions) had questions regarding socio-demographic characteristics; the second part (12 questions) contained questions related to willingness to be a deceased organ donor and the third part (5 questions) contained descriptive questionnaires. Willingness for cadaveric organ donation was measured via participant's response to two questions: Are you willing to donate your organ(s) to the person who is in the need of organ transplant after your death?" and “if you are given to sign an organ donation card to register your name for organ donation after your death, would you sign it?" Participants were given the response options “Yes,” “No” and “Not sure.” They were considered “willing” to be deceased organ donors only if the response was “Yes” to both these questions.

As the permission was taken from the class coordinators only in law and mass communication colleges. Medical students were distributed questions via links and in places they could be reached and felt comfortable inside the hospital premises. Medical students are not as readily available in class, as compared to law or mass communication students. Introduction of the researcher, research topic and its importance was explained in detail. Written informed consent was taken and self-administered questionnaires were distributed in Nepali as well as in English- as per the convenience of the participants. A total of around 30 minutes was provided for its completion. Most of the forms were collected at the time of recruitment. Those who could not submit on the same day were asked to leave the completed forms in the reception of the college or to anyone who volunteered to help with the collection of completed forms, who were later contacted by telephone.

Study variables

Dependent and independent variables

Our study's dependent variable is willingness to be a deceased organ donor; and our independent variables were socio-demographic variables including education, course of study, age, sex, religion, marital status, family type, and total monthly family income.

Covariates

The following were selected as covariates: Attendance at a conference or general talk on organ donation, family objection in one's wish of organ donation, knowing somebody with organ failure, knowing someone who has donated organs, relationship with the potential recipient, age of potential recipient, perception that doctors will leave body disfigured after organ donation, and presence of chronic disease in one's family.

Statistical analysis

Collected data was entered in Microsoft Excel 2007. Microsoft excel sheet was subsequently converted into Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 1 1.5 for statistical analysis. Frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation (S.D.) were calculated. Graphical and tabular presentations were used wherever appropriate. Similarly, the dependent dummy variable was created and value “1” was assigned for willingness and “0” for otherwise.

Chi-square test was used to analyze the association between categorical independent variables and a dependent variable at 95% confidence interval (C.I.). Binary logistic regression was performed to estimate odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (C.I). Explanatory variables that were significant in bivariate analysis at the level of <0.05 were taken for multivariate analysis.

Ethical approval

Before the data collection, this research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of B.P Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal.

Results

Out of 440 forms distributed, 43 forms were incomplete. Thus, the total number of respondents enrolled in the study was 397; 117 from medicine, 156 from law and 124 from mass communication specialty.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Most of the respondents were law students (39.3%), followed by mass communication (31.2%) and medical (29.5%) students, respectively. More than half (52.9%) of the respondents were male, while the composition of females was 47.1%. A majority (88.4%) of the respondents practiced Hinduism. Most (66.2%) of the respondents were single. The proportion of respondents living in nuclear families was 71.5%. The mean age of the respondents was 28.59 years. The average household income per month was nearly 603.4 USD (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Category | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education stream | |||

| Law | 156 | 39.3 | |

| Mass communication | 124 | 31.2 | |

| Medical | 117 | 29.5 | |

| Age | |||

| Mean±SD=28.59±3.94 | |||

| 20-30 years | 309 | 77.8 | |

| 31 -45 years | 88 | 22.2 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 210 | 52.9 | |

| Female | 187 | 47.1 | |

| Religion | |||

| Hindu | 351 | 88.4 | |

| Buddhist | 23 | 5.8 | |

| Muslim | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Christian | 19 | 4.8 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 263 | 66.2 | |

| Married | 134 | 33.8 | |

| Type of family | |||

| Nuclear | 284 | 71.5 | |

| Joint | 113 | 28.5 | |

| Total monthly family income | |||

| Mean=603.4 USD | |||

| Inadequate (≤ 325 USD) | 122 | 30.7 | |

| Adequate (>325 USD) | 275 | 69.3 | |

Adequate and Inadequate total monthly income of the family: According to the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) in 2017, Nepal, average household expenditure in urban areas was nearly 321.4 USD (Nrs. 36, 000). Thus, a family was considered to having adequate income if the total monthly income was more than 325 USD.38

Willingness to become deceased organ donors

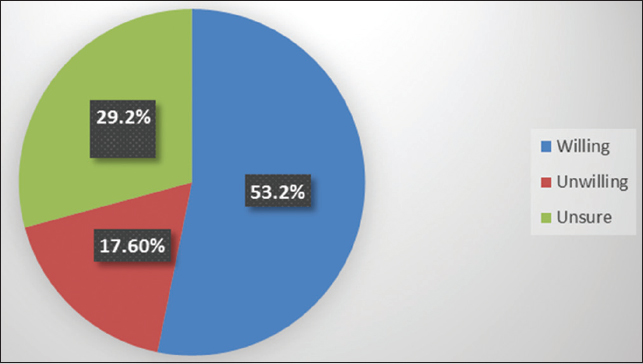

The largest group than half of the respondents (53.2%) reported willingness towards donating their organs after death. Though interested in organ donation, 29.2% of the respondents were unsure about signing an organ donation card, whilst 17.6% were not in favor of donating their organs after death (Figure 1).

- Distribution of willingness to become deceased organ donors

Independent factors and willingness to be deceased organ donors

Attending any conference or general talk on organ donation (p<0.001), family objection in one's wish in donating one's organs (p<0.001), knowing someone who had donated organs (p<0.001), perception that organ donation is prohibited by one's religion (p<0.001), knowing someone with any kind of organ failure (p=0.002), relationship with the prospective recipient (p=0.004), having someone in family with any kind of chronic disease (p=0.013) and perception that body is left disfigured by doctors after organ extraction (p=0.04) were selected to be analyzed further in binary logistic regression (Table 2).

| Factors | Category | Willingness | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (n=211) | No (n=186) | |||

| Education stream | ||||

| Medical | 71 (60.7%) | 46 (39.3%) | 0.134 | |

| Law | 76 (48.7%) | 80 (51.3%) | ||

| Mass com. | 64 (51.6) | 60 (48.4%) | ||

| Age in years | ||||

| 20-30 | 163 (52.8%) | 146 (47.2%) | 0.766 | |

| 31-40 | 48 (54.5%) | 40 (45.5%) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 112 (53.3%) | 98 (46.7) | 0.938 | |

| Female | 99 (52.9%) | 88 (47.1%) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 139 (52.9%) | 124 (47.1%) | 0.868 | |

| Married | 72 (53.7%) | 62 (46.3%) | ||

| Family type | ||||

| Nuclear | 144 (50.7%) | 140 (49.3%) | 0.122 | |

| Joint | 67 (59.3%) | 46 (40.7%) | ||

| Total monthly income of the family (In rupees) | ||||

| Inadequate | 61 (50%) | 61 (50%) | 0.420 | |

| Adequate | 149 (54.4%) | 126 (45.9%) | ||

| Attended any conference or general talk on organ donation | ||||

| Yes | 73 (80.2%) | 18 (19.8%) | <0.001 | |

| No | 138 (45.1%) | 168 (54.9%) | ||

| Perception that organ donation is prohibited by one's religion | ||||

| Yes | 3 (18.8%) | 13 (81.2%) | <0.001 | |

| No | 194 (59.1%) | 134 (40.9%) | ||

| Don't know | 14 (26.4%) | 39 (73.6%) | ||

| Family objection in one's wish in organ donation | ||||

| Yes | 5 (6.4%) | 73 (93.6%) | <0.001 | |

| No | 161 (78.9%) | 43 (21.1%) | ||

| Don't know | 45 (39.1%) | 70 (60.9%) | ||

| Knows someone who has donated his organ dead/alive | ||||

| Yes | 72 (76.6%) | 22 (23.4%) | <0.001 | |

| No | 139 (45.9%) | 164 (54.1%) | ||

| Knows someone who has some kind of organ failure | ||||

| Yes | 106 (62%) | 65 (38%) | 0.002 | |

| No | 105 (46.5%) | 121 (53.5%) | ||

| Relation with prospective recipient | ||||

| Only family members | 6 (25%) | 18 (75%) | 0.004 | |

| Anyone in need | 205 (55%) | 168 (45%) | ||

| Age of the recipient | ||||

| Young people | 6 (42.9%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0.432 | |

| Anyone in need | 205 (53.5%) | 179 (46.5%) | ||

| Perception that body will be left disfigured after organ extraction | ||||

| Yes | 13 (37.1%) | 22 (62.9%) | 0.047 | |

| No | 198 (54.7%) | 164 (45.3%) | ||

| Has someone in family with any kind of chronic disease | ||||

| Yes | 126 (58.9%) | 88 (41.1%) | 0.013 | |

| No | 85 (46.4%) | 98 (53.6%) | ||

Predictors of willingness to be deceased organ donors

Family permission in one's wish to donate organs (OR=42.56, 95% CI= 15.74-115.08, p<0.001), having someone in family with any kind of chronic disease (OR=2.05,95% CI=1.21-3.49, p=0.008), having attended any conference or general talk on organ donation (OR=2.43, 95% CI= 1.24-4.76, p=0.009), knowing someone who has donated organ dead or alive (OR=2.20, 95% 0=1.14-4.26, p=0.018), knowledge that body will not be left disfigured after organ extraction (OR=2.92, 95% 0=1.13-7.53, p=0.026) were found to be the significant predictors for willingness for cadaveric organ donation after adjusting for confounders in the logistic regression (Table 3).

| Factors | Category | Regression Coefficient (β) | OR | 95% C.I. for OR | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Family objection in one's wish in organ donation | ||||||

| Yes (Ref) | ||||||

| No | 3.75 | 42.56 | 15.74 | 115.08 | <0.001 | |

| Don't know | 1.93 | 6.93 | 2.52 | 0.39 | <0.001 | |

| Has someone in family with any kind of chronic disease | ||||||

| No (Ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.72 | 2.05 | 1.21 | 3.49 | 0.008 | |

| Has attended any conference or general talk on organ donation | ||||||

| No (Ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.89 | 2.43 | 1.24 | 4.76 | 0.009 | |

| Knows someone who has donated his organs dead/alive | ||||||

| No (Ref) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.79 | 2.20 | 1.14 | 4.26 | 0.018 | |

| Perception that body is left disfigured after organ extraction | ||||||

| Yes (Ref) | ||||||

| No | 1.07 | 2.92 | 1.13 | 7.53 | 0.026 | |

Willingness and unwillingness to donate organs after one's death

Three-fourth (75.82%) of respondents cited “organ donation is a humanitarian duty” followed by “motivated by friends/family” (19.4%) for the reason of their willingness towards cadaveric organ donation (Figure 2). Similarly, the major reasons for unwillingness towards cadaveric organ donation cited by respondents were “inadequate information” (48.38%) followed by “No faith in health system” (23.6%), “Lack of family support” (21.5%) and “Not supported by religion” (6.40%) respectively.

- Reasons for willingness to become deceased organ donors

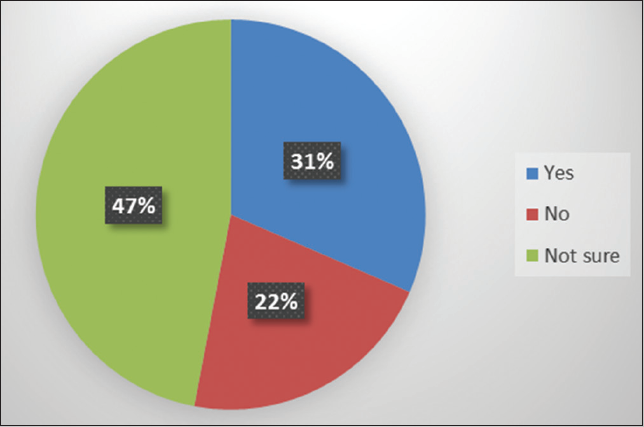

Willingness to donate family member's organs upon their death

Nearly one-third (31.5%) of the respondents reported they were willing to consent to donate the viable organs of any of their family members upon their death. However, 47% of the people were unsure, and the most commonly cited reasons were: “it will depend upon the situation” and “If I know beforehand about their wish to donate organs I will otherwise I won't.” Just over 20% (21.5%) of the respondents said they wouldn't want to consent to donate a family member's organs because they feel they do not have any rights to make decision over someone else's body and they do not want to see the bodies of their loved ones go under knives (Figure 3).

- Willingness to donate family member's organs upon their deaths

Perceived impediments to deceased organ donation

About 77% of the respondents reported “lack of awareness” as the prime factor hindering deceased organ donation in Nepal. “Weak legal provisions” was thought to be the barrier for deceased organ donation by about 13% of the respondents. “Lack of competent surgeons” and “flaccid efforts in making organ donation cards easily available” were cited by 5% and 1.5% of the respondents, respectively, as a hindrance for deceased organ donation.

Discussion

The overall willingness of the participants in this study to be deceased organ was 53.2%. This corresponds and contradicts many studies from different parts of the world. Similar findings were observed in the studies carried out in Qatar, where willingness was 57.3%,16 India, where willingness was 57.3%,25 Malaysia, where willingness was 55.6%,26 Turkey, where willingness was 51.3%,24 Korea, where willingness was 49.8%27 and China, where willingness was 49.3.28 However, contradictory results were shown in studies conducted in South India, where willingness was 89%4 and Turkey, where willingness was 72%.29 The proportion of people who were willing to be deceased organ donors ranged from 21% to 90% in various studies.2,4,14,29,30

In the present study, though a majority of the respondents exhibiting willingness for deceased organ donation were from the medical studies program, it was not statistically significant. This is in contrast with studies in China28 and Turkey,24,29 where mostly medical students were more willing to donate organs than other academic specialties. Gender was not determinative of willingness to donate organs in our study. This result differs from studies in Qatar,16,31 and Malaysia,32 where female gender was significantly associated with willingness to donate organs after death.

In our study, monthly income was not significant, which is consistent with a study in Malaysia.26 However, monthly income was found to be positively or negatively associated with organ donation in studies done in Qatar,16 South India,4 and Pakistan.33 Though respondents' perceptions that their religion supports organ donation was highly significant with willingness for organ donation in the bivariate analysis, it was insignificant in final multivariate logistic regression. This result contrasts with a study in Malaysia in which, the respondents who said their religion permits organ donation were five times more willing to donate organs than others.26 Few other studies in Pakistan,33 India,30 Malaysia,32,26 have shown that religion was significant for willingness to donate organs. The contrasting findings may be because a majority of respondents in the present study are Hindus and thus, there is less variation in religion.

Marital status and family type were unassociated with willingness for deceased organ donation in the present study. This result does not follow the result of the study done in South India, where marital status (single) and family type (nuclear) were positively associated with willingness to donate organs.4 Relationship with the prospective recipient and age of the recipient were not significantly associated with willingness to donate organs in the present study. However, studies in India30,31 showed a significant association between relationship with the recipient and willingness to donate organs. Family objection to one's willingness to be a deceased organ donor was highly significant in the present study. This result corresponds with a study in Malaysia.26 This fact suggests that willingness could be improved by enhancing families' attitude towards organ donation.6 In the present study, knowing someone who has donated organs is significantly associated with willingness for deceased organ donation. This result is supported by a study in done in New Zealand.34

A majority (91%) of the respondents in this study believed that the body is not left disfigured after organ extraction by doctors. This perception was significantly associated with willingness to donate organs. Similar finding were reported in a study done in South India where 88% believe that the body won't be left disfigured after organ removal.4 Willingness to donate the organs of one's family members in this study was only 31.5%. This result was 41.2% in a study done in North India,30 69% in a study done in South India4 and 42% in a study done in New Zealand.34 The respondents who were unwilling to consent to donate family member's organs indicated that they have no rights to make decision for someone else's body. If they knew of their family members' wish to donate organs before their deaths, they would, otherwise they would not. Similar reasons were exhibited by the respondents in a study done in Turkey.24,29

The most frequent reason cited for the unwillingness to donate organs among respondents in the present study was the belief that they lack sufficient knowledge regarding organ donation to make the decision (48.38%), followed by no faith in health system (23.6%) and lack of family support (21.5%). Lack of adequate information to make a decision for organ donation was also quoted by majority of respondents in a study done in Turkey.35 In contrast, in a study done in Pondicherry, the most common barrier (83%) was “opposition from family members.”36

Three-quarters of the respondents cited “organ donation is a humanitarian duty” as a reason for their willingness for cadaveric organ donation. This reason is consistent with the reasons given by respondents in a study done in Pondicherry36 and Turkey.29

People who had attended any conference or general talk on organ donation were 2.4 times more likely to donate organs than their counterparts in our study. Slightly more than one-fifth (23%) of respondents, mainly medical students, reported having attended a conference or talk on organ donation. This is similar to a study in China, where 1 7.4% reported attending a conference on organ donation and, most of them were doctors.28 A notable proportion (91%) of the respondents believe extensive awareness programs and health education on organ donation are immediate measures to increase the number of people registering their names for deceased organ donation. This finding is in line with studies done in Tamil Nadu,31 Qatar,16 and Turkey.24

No respondents in the present study carried an organ donation card. This corresponds with a result of study in Ahmedabad, Western India.12 The most likely reason is that there hasn't been remarkable efforts in advocating for deceased organ donation. Moreover, donation is an emerging concept in Nepal and it had been just two year since the new Transplant Act was promulgated. Another factor may be that deceased donor organ transplantation was not conducted in the country at the time of data collection.

Limitations

The correlation between variables does not necessarily mean causation. As this study was conducted among the educated classes of the society, the results may not portray the broader views of the general population. Thus, it is important for new studies to understand the general views of the population regarding deceased organ donation. Nevertheless, the sample populations included in this study (medical, mass communication and law students) will play an important role in carrying out the legal, medical and socio-cultural aspects of organ donation program and policies as deceased organ donation and transplantation grows in Nepal.

Conclusion and Implications for Translation

Of respondents in this study, 53.2% expressed willingness to be a deceased organ donor themselves. However, only 31.5% showed willingness towards donating a family member's organs upon their death. Thus, the survey revealed that a significant proportion of people were willing to donate their organs. However, how many of these will actually donate in a real scenario is unknown. This calls for making organ donation cards more readily available and motivating people to register their names for deceased organ donation, thus transforming their “willingness” into “commitment” to donate organs. There is a large influence of family attitude on willingness to donate organs. Willingness could be improved by enhancing families' attitudes towards organ donation. Thus, there is a need for mass awareness and motivational programs. People find it difficult to consent to donate a family member's organs because of the rational grounds of respecting someone else's body. This highlights the importance of registering prospective organ donors. The findings of this study may serve as a baseline for other studies and could help policy makers devise policies and strategies by addressing factors that hinder willingness to be a registered organ donor.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure:

Not Applicable.

Ethics Approval:

The Institutional Review Council of BP Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal approved the study.

Disclaimer:

None.

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge School of Public Health and Community Medicine, BPKJHS, Shahid Dharmabhakta National Transplant Center, Ms. Sarah Rasmussen and Mr. Dharanidhar Baral and all the participants, without whose support this study would not have been a reality. We are obliged towards Global Health and Education Projects, Inc. (GHEP) for their publication support. Likewise, we thank the Scientific Committee of Global Public Health Congress: Annual Congress on Nutrition and Healthcare held in Paris, France from October 18-20, 2018 for giving space to our abstract in their Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences.37

Funding/Support:

This publication is fully supported by the Global Health and Education Projects, Inc. (GHEP) under the Emerging Scholar's Grant Program (ESGP). The information, contents, and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of nor should any endorsements be inferred by ESGP or GHEP.

References

- Organ donation. Wikipedia; (accessed )

- Attitudes and awareness regarding organ donation in the western region of Sao Paulo, Brazil. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(2):1835.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, religious beliefs and perception towards organ donation from death row prisoners from the perspective of patients and non-patients in Malaysia: A preliminary study. Int J Humanities Soc Sci. 2012;2(24):197-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organ donation, awareness, attitudes and beliefs among post graduate medical students. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21(1):174.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Awareness and attitudes toward organ donation in rural Puducherry, India. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2016;6(5):286-290.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude and behaviour of the general population towards organ donation: An Indian perspective. Natl Med J India. 2016;29(5):257.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Kidney Foundation; (accessed )

- NHS blood and transplant reveals nearly 49,000 people in the UK have had to wait for a transplant in the last decade. NHS Blood and Transplant. Published November 20, 2015 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Third WHO global consultation on organ donation and transplantation: striving to achieve self-sufficiency, March 23-25, 2010, Madrid, Spain. Transplantation. 2011;91:S27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge regarding organ donation and willingness to donate among health workers in South-West Nigeria. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2016;7(1):19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitude and awareness towards organ donation in western India. Ren Fail. 2015;37(4):582-588.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude towards organ donation in rural Kerala. Acad Med J India. 2014;2(1):25-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitudes about organ donation among medical students. Tx Med. 2006;18(2):91-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing families' consent for donation of solid organs for transplantation. JAMA. 2001;286(1):71-77.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing organ donation and transplantation in State of Qatar. Tx Med. 2006;18:97-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and attitude of nursing students regarding organ transplantation. J Chitwan Med Coll. 2017;5(3):60-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Need for renal transplantation program in Bir Hospital. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2005;3:191-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- Renal transplantation in Nepal: the first year's experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21(3):559-564.

- [Google Scholar]

- New hope in organ transplantation in Nepal: the amendment of the Transplant Act 2072. 2016

- [Google Scholar]

- Brain death and organ donation: knowledge, awareness, and attitudes of medical, law, divinity, nursing and communication students. Transplant Proc 2015

- [Google Scholar]

- Are medical students having enough knowledge about organ donation. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015;14(7):29-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with medical and nursing students' willingness to donate organs. Medicine. 2016;95(12):e3178.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge and opinions of deceased organ donation among middle and high school students in Korea. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(10):2805-2809.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness toward organ donation among health professionals in China. Transplantation. 2015;99(7):1379-1385.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge levels of and attitudes to organ donation and transplantation among university students. North Clin Istanb. 2015;2(1):19.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitude and practices of organ donation among college students in Chennai. Stanley Med J. 2014;1(1):11-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on knowledge, attitude and practices about organ donation among college students in Chennai, Tamil Nadu-2012. Prog Health Sci. 2013;3(2):59.

- [Google Scholar]

- The influence of socioeconomic and demographic variables on willingness to donate cadaveric human organs in Malaysia. Medicine. 2014;93(23):e126.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge, attitudes and practices survey on organ donation among a selected adult population of Rakistan. BMC Med Ethics. 2009;10(1):5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand university students' knowledge and attitudes to organ and tissue donation. N Z Med J. 2015;128(1418):70-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes of Turkish medical and law students towards the organ donation. Int J Organ Transplant Med. 2015;6(1):1.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on public intention to donate organ: perceived barriers and facilitators. Brit J Med Pract. 2013;6(4):42-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global public health congress: annual congress on nutrition & healthcare. J Nutr Food Sci. 2008;8:69.

- [Google Scholar]

- An average Nepali spends Rs 70,680 yearly. Himalayan News Service. Rublished April 7, 2017 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]