Translate this page into:

Effectiveness of a Community Level Maternal Health Intervention in Improving Uptake of Postnatal Care in Migori County, Kenya

✉Corresponding author email: mwangiguk@gmail.com

Abstract

Background:

Provision of a continuum of care during pregnancy, delivery, and the postnatal period results in reduced maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. Complications and lack of skilled postnatal care has negative consequences for mothers and babies. We examined to what extent a community level integrated maternal health intervention contributed to improvements in uptake of postnatal care.

Methods:

An Ex post quasi-experimental design was applied. A population of 590 reproductive-aged women was used to assess the effectiveness of a community level integrated maternal health intervention, and to determine the predictors of uptake of postnatal care. Descriptive, bivariate and multivariate analyses were conducted.

Results:

About three fifths (64%) of the women reported having sought postnatal care services at a healthcare facility within six (6) weeks. Women in the intervention group were 3.3 times more likely to uptake postnatal care at a healthcare facility (Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR)= 3.31 [95% CI 1.245 to 8.804] p=0.016). Women referred to the healthcare facility for postnatal care by Community Health Workers (CHWs), were 2.72 times more likely to uptake the services (AOR= 2.72 [95% CI 1.05 to 7.07] p=0.039), than those not referred by CHWs. Distance to health facility 61% was identified as the major barrier, to uptake of postnatal care, while some mothers reported not feeling the need for postnatal care (11%).

Conclusion and Implications for Translation:

Routine health education by trained providers at community level health facilities, coupled with enhanced CHWs' involvement can improve uptake of postnatal care. Ignorance and accessibility challenges were some of the identified barriers to the uptake of postnatal care.

Keywords

Community

Maternal

Health

Intervention

Postnatal Care

Kenya

MAISHA

Community Health Volunteers (CHVs)

Community Health Workers (CHWs)

Introduction

Background of the Study

Skilled care during pregnancy, delivery and postnatal period is important for the health of both mothers and newborns. Most of the maternal and neonatal mortalities occur at the community level due to lack of good quality care during labor and birth.1

Worldwide, the maternal mortality ratio has fallen since 1990– most likely due to improved access to skilled care and to antenatal care.2 Nonetheless, in 2010, approximately 287,000 women died during childbirth or from pregnancy complications; most of them in poorer countries.2 Improved access to skilled health personnel during childbirth is a priority strategy and a key indicator for the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) 5a which sought to improve maternal health. This was also reflected in Sustainable Development Goal 3.1 vide: “by 2030 reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births.”2

Provision of a continuum of care during pregnancy, delivery, and the postnatal period results in reduced maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.3 Kenya's maternal mortality ratio is still high (362 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births) and under-five child mortality (52 per 1000 live births) with mortality occurring in the first month of life being 39 deaths per 1,000 live births.4 In 2012, the government of Kenya launched a new policy on population and national development. The policy described in the Sessional Paper No. 3 of 2012, was aimed at: reducing the infant mortality rate from 52 per 1,000 live births in 2009 to 25 per 1,000 live births by 2030; reducing the under-5 mortality rate from 74 per 1,000 live births in 2009 to 48 per 1,000 live births by 2030; and reducing the maternal mortality rate from 488 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2009 to 200 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030.5 Only slightly more than half (53 percent) of women who gave birth in the two years before the 2014 Kenya Demographic and Health Survey received a postnatal care checkup in the first two days after delivery and only 36% had their first postnatal checkup.5 One in three newborns received postnatal care from a doctor, a nurse, or a midwife. Overall, 43 percent of women did not receive a postnatal checkup within the first six weeks after delivery.5

Evidence suggests that integrated community- based services provided starting from pre-pregnancy through the postnatal period can improve maternal and neonatal outcomes.6-8 Furthermore, there is growing evidence for effective low cost interventions to reduce the rate of maternal and newborn deaths.9-14 A key part of these evidence based interventions is the reduction of deliveries with an unskilled birth attendant in combination with early identification of danger signs in a mother or newborn. Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) and Community Health Workers (CHWs) form broad categories of non-professional health workers who are often the first point of contact in these interventions and provide essential links to clinical services.15

However, more research is needed to explore regional variability, examine longitudinal trends, and study the impact of interventions to boost rates of skilled care utilization in sub-Saharan Africa.16 Maternal and neonatal deaths in Kenya are attributed to limited utilization and availability of skilled birth attendants (SBA), low coverage of basic and normal delivery services and poor quality of existing services.4 The government of Kenya and its partners have rolled out nation-wide maternal and child health programs. These programs play key roles in the improvement of maternal-child health indicators. Despite the efforts, huge disparities are notable across the counties. This implies presence of unique determinants and barriers to the uptake of skilled care after delivery (postnatal care) for these counties. This study examines the effectiveness of a community level integrated maternal health intervention and predictors of uptake of postnatal care.

Objectives of the Study

This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of a community level integrated maternal health intervention geared towards increasing the uptake of postnatal care. Further, this study sought to establish the determinants and explore the barriers to uptake of postnatal care. The study hypothesized that a community level intervention would not lead to improved uptake of postnatal care (null). Specifically, the study focused on determining the proportion of women aged 15-49 years utilizing postnatal care services at a healthcare facility in Migori and Rongo Sub-Counties in South western Kenya.

Methods

This study was carried out in Migori County in Kenya. Migori County is located in western Kenya and borders Homa Bay County (North), Kisii County (North East), Narok (South East), Tanzania (West and South) and Lake Victoria to the West. The county also borders Uganda via Migingo Island in Lake Victoria. The intervention arm was Migori Sub-County and the control group was Rongo Sub-County. An Ex post (retrospective non-equivalent control group design) type of quasi-experimental study was conducted. We evaluated the effectiveness of a community level Maternal-Infant program dubbed Maternal and Infant Survival for Health care Advancement (MAISHA) in improving uptake of postnatal care. The study population were women of reproductive age who delivered between January 2014 and December 2016 in both Sub-Counties. Migori County had an estimate of 43,440, 44,765 and 44,130 live births during the years of 2014, 2015 and 2016, respectively.

Sample size was determined using healthcare facility delivery as a binary outcome using a binomial test to compare one proportion to a reference value. Using a power of 0.85 and alpha of 0.05 and by taking a ratio of controls to treatment in sample to be 1, a sample size of 582 women of reproductive age (Migori (291) and Rongo (291) was needed to detect a difference of 11.7 per 100 live births in a healthcare facility from the rate of 53.3% (births assisted by trained professional in Migori, MAISHA baseline, 2013) and percent of the intervention group with an outcome targeted to be 65% (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) 2014, Nyanza region SBA 65%). A proportional stratified sampling method was used to give all sub-locations equal chance of selection despite differing population densities. Migori Sub-County has 30, while Rongo has 22 sub-locations (Source: Migori County Development profile [2013]). A sample of 11 and 15 respondents was selected in each of the Migori and Rongo Sub-Counties respectively.

The control group (Rongo Sub-County) received conventional care from the Ministry of Health Kenya and the Migori County government. In the intervention arm (Migori Sub-County), healthcare workers operating within the Ministry of Health's policy on Community Strategy, Community Health Extension Workers (CHEWs), were trained on various relevant aspects of maternal-neonatal and child health Maternal-Neonatal and Child Health (MNCH) and were aided in the establishment and activation of community units. The CHEWs then embarked on sensitizing and training volunteers in their community units on MNCH.

The community volunteers then sensitized and educated respective households within the Migori intervention group on MNCH, with with special emphasis in reaching all unskilled birth attendants and urging them to advise, refer and act as birth companions during (SBA) and postnatal care. In all instances of sensitization, the single overriding objective and message was to encourage postnatal mothers to always seek skilled care services as scheduled after delivery. Clinical health personnel conducting postnatal evaluations and care within this county were trained, and essential obstretic care kits were facilitated to the corresponding healthcare facilities.

Study Variables

The main outcome variable was uptake of postnatal care. We further assessed predictors of utilization of postnatal care among the participants.

Statistical Analysis

The coded data were entered into a computer database using Stata 11.2 data editor (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical analysis was both analytical and descriptive. Chi-square test of significance and multivariate logistic regression analysis were performed.

Ethical Approval

Scientific and ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Kenyatta University Ethical Review Committee (KUERC) - Application number PKU/487/E41. Written informed consent was obtained from the participants, participation was fully voluntary and confidentiality was observed at all times.

Results

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants in the two Sub-Counties were generally comparable. Migori reported a relatively higher proportion of women aged 15-49 years utilizing postnatal care services at a health facility (98%, 292) than Rongo Sub-County (93.49%, 273). The age of the respondents ranged between 15 to 49 years. Most of the women were aged between 20 to 29 years. The median age was 24 and 25 years in Migori and Rongo Sub-county respectively. The majority of women in Migori (96%, 286) and Rongo Sub-County (90.8%, 265) reported having a mobile phone. It was also found that only a few women in Migori (12.4%, 37) and in Rongo Sub-County (7.5%, 22) were registered in the National Hospital Insurance Fund (NHIF). Refer to Table 1 for a summary of the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Factor | Migori (N=298) | Rongo (N=292) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean | 25.7 | 26 | |

| Standard deviation | 6.6 | 6.2 | |

| Range | 15-46 | 15-49 | |

| Freq. (Percent) | Freq. (Percent) | ||

| Age category | |||

| 15-19 | 53 (17.8) | 34 (11.6) | |

| 20-24 | 98 (32.9) | 109 (37.3) | |

| 25-29 | 67 (22.5) | 75 (25.7) | |

| 30-34 | 49 (16.4) | 46 (15.8) | |

| 35-39 | 19 (6.4) | 18 (6.2) | |

| 40-44 | 8 (2.7) | 7 (2.4) | |

| 45-49 | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.03) | |

| Has mobile No. | |||

| Yes | 286 (96.0) | 265 (90.8) | |

| No | 12 (4.0) | 27 (9.3) | |

| Registered with NHIF | |||

| Yes | 37 (12.4) | 22 (7.5) | |

| No | 261 (87.6) | 270 (92.5) | |

| In polygamous marriage | |||

| Yes | 79 (26.5) | 44 (15.1) | |

| No | 219 (73.5) | 248 (84.9) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 32 (10.7) | 25 (8.6) | |

| Widowed | 11 (3.7) | 6 (2.1) | |

| Married | 255 (85.6) | 261 (89.4) | |

Postnatal Care Service Utilization

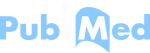

For those women who reported utilization of post natal services at the health facility, overall, in the two Sub-Counties, 362 (63.96%) of the women reported having sought for postnatal care services at the health facility within 6 weeks. The proportion of women seeking postnatal care services within 6 weeks was similar in the two Sub-Counties (188, 63.74% and 174, 64.16% in Rongo and Migori respectively) (Figure 1). Although there was only a small difference in the proportion of those who sought postnatal care in the multivariate analysis, women in the intervention Sub-County (Migori) were found to be 3.3 times more likely to take up postnatal care at a health facility [AOR =3.31, 95% Conf. Interval (1.244574, 8.803599), pr=0.016] compared to those who did not receive the intervention.

- Postnatal care service utilization

Barriers to uptake of postnatal care

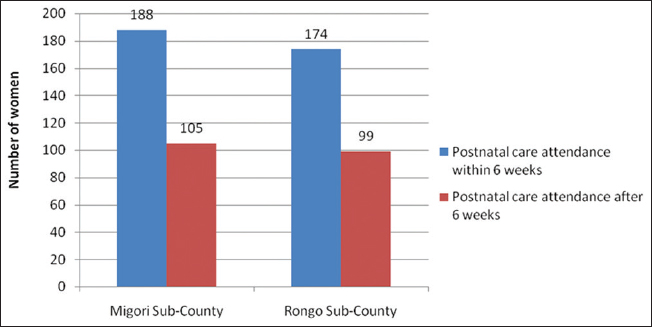

Though the number of women who failed to attend postnatal care was quite low, distance to health facility and cost of transport were cited as barriers. Some mothers felt no need for postnatal care, possibly due to ignorance and failure to get the right health education (Figure 2).

- Reasons for failure to seek postnatal care

Factors associated with the uptake of postnatal care in Migori Sub-County

Being in the intervention arm was significantly associated with uptake of postnatal care. (Pearson chi2(I) = 7.3387 Pr = 0.007). The number of pregnancies ever had, live births, number of living children, whether they attended the Antenatal Care (ANC), the number of ANC visits, the person conducting health education and the mode of transport used were found to be statistically significantly associated with uptake of postnatal care at a health facility (Table 2).

| Factor | Postnatal care at 6 weeks (n=188) | Chi - square | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Possess mobile phone | - | 3.0125 | 0.222 |

| Number of pregnancies | - | 43.9025 | 0.004 |

| Live births | - | 44.9850 | 0.001 |

| Living children | - | 41.9492 | 0.001 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 25 | 9.8527 | 0.043 |

| Widowed | 8 | - | - |

| Married | 155 | - | - |

| In polygamous marriage | |||

| Yes | 42 | 2.3497 | 0.125 |

| No | 146 | - | - |

| Registered with NHIF | |||

| Yes | 42 | 4.6539 | 0.098 |

| No | 146 | - | - |

| Woman's educational level | |||

| Primary | 144 | 7.9596 | 0.241 |

| Secondary | 33 | - | - |

| College/university | 11 | - | - |

| Woman's occupation | - | 22.7622 | 0.012 |

| Partner's education level | - | 8.2520 | 0.409 |

| Partner's occupation | - | 22.1054 | 0.036 |

| Attended ANC | - | 18.5276 | 0.000 |

| Number of ANC visits | - | 29.4983 | 0.000 |

| Received health education | |||

| Yes | 179 | 2.2565 | 0.324 |

| No | 9 | - | - |

| Person health educating | - | 84.7757 | 0.000 |

| Referred to facility | |||

| Yes | 24 | 1.1427 | 0.565 |

| No | 164 | - | - |

| Referring person | - | 25.5698 | 0.029 |

| Had birth companion | |||

| Yes | 24 | 0.3232 | 0.851 |

| No | 164 | - | - |

| Person accompanying | - | 28.8317 | 0.050 |

| Mode of transport used | - | 34.7049 | 0.000 |

| Time taken to facility | - | 16.4806 | 0.011 |

Factors associated with the uptake of postnatal care in Rongo Sub-County

The women's occupation, the number of ANC visits, the person conducting health education, whether the women were referred to a healthcare facility, and the person accompanying the woman in question were found to be statistically significantly associated with uptake of postnatal care at a healthcare facility. Among the factors found not to be significantly associated with uptake of postnatal care at a healthcare facility were the mode of transport used, having a birth companion, receipt of health education, whether the women attended ANC, the partner's education level, marital status, whether the women were registered with the NHIF, if the women were in a polygamous marriage, the number of pregnancies, live births, number of living children, and the women's educational level (Table 3).

| Factor | Postnatal care at 6 weeks (n=174) | Chi - square | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Possess mobile phone | - | 4.5839 | 0.032 |

| Number of pregnancies | - | 22.4646 | 0.316 |

| Live births | - | 13.9407 | 0.733 |

| Living children | - | 14.7537 | 0.790 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 18 | 4.6379 | 0.322 |

| Widowed | 2 | - | - |

| Married | 154 | - | - |

| In polygamous marriage | |||

| Yes | 25 | 0.5989 | 0.741 |

| No | 149 | - | - |

| Registered with NHIF | |||

| Yes | 14 | 0.2366 | 0.888 |

| No | 160 | - | - |

| Woman's educational level | |||

| Primary | 137 | 9.3910 | 0.153 |

| Secondary | 35 | - | - |

| College/university | 2 | - | - |

| Woman's occupation | - | 25.2159 | 0.005 |

| Partner's education level | - | 7.7739 | 0.456 |

| Partner's occupation | - | 19.4644 | 0.035 |

| Attended ANC | - | 2.0556 | 0.358 |

| Number of ANC visits | - | 24.3769 | 0.002 |

| Received health education | |||

| Yes | 171 | 5.0281 | 0.081 |

| No | 3 | - | - |

| Person health educating | - | 50.9624 | 0.000 |

| Referred to facility | |||

| Yes | 29 | 10.1545 | 0.006 |

| No | 145 | - | - |

| Referring person | - | 16.1634 | 0.040 |

| Had birth companion | |||

| Yes | 22 | 1.4918 | 0.474 |

| No | 152 | - | - |

| Person accompanying | - | 72.6011 | 0.000 |

| Mode of transport used | - | 11.3366 | 0.079 |

| Time taken to facility | - | 16.3354 | 0.012 |

Determinants of uptake of postnatal care

Participants who received health education were 2.98 times more likely to return for postnatal care (AOR= 2.98 [95% CI 0.7177 to 12.36] p=0.133), while those who received health messages from health workers had a 9.63 times greater likelihood to seek postnatal care (AOR= 9.63 [95% CI 2.09 to 44.38] p=0.004). Women referred to the health facility for postnatal care by Community Health Workers were 2.72 times more likely to take up the services (AOR= 2.72 [95% CI 1.05 to 7.07] p=0.039).

Women in the intervention arm (Migori Sub-County) of the study who were beneficiaries of the integrated maternal-child project (MAISHA) were 3.3 times more likely to take up postnatal care in a health facility than their counterparts in the Rongo control Sub-County (AOR= 3.31 [95% CI 1.245 to 8.804] p=0.016). Those who took between 30 minutes to 1 hour to get to a healthcare facility were 6 times less likely to utilize postnatal care services (AOR= 0.1663 [95% CI 0.0536 to 0.5155] p=0.002). Accessibility to a health facility and their distribution within a region is vital in determining the uptake of services.

Discussion

This study sought to determine the proportion of women aged 15-49 years utilizing postnatal care services at a healthcare facility in Migori and Rongo Sub-Counties in South western Kenya. Further, the study focused on establishing the determinants and on exploring the barriers to postnatal care uptake. Women in the Migori Sub-County intervention arm reported a relatively higher proportion for utilizing postnatal care services at a health facility (98%, 292) than the Rongo Sub-County control group (93.49%, 273).

The intervention arm was 3.3 times more likely to take up postnatal care in a health facility than their counterparts in the control. Participants who received health education were 2.98 times more likely to return for postnatal care (AOR= 2.98) while those who received health messages from health workers had a 9.63 times greater likelihood to seek postnatal care (AOR= 9.63). Women referred to the health facility for postnatal care by Community Health Workers were 2.72 times likely to take up the services (AOR= 2.72). Though the number of women who failed to attend postnatal care was quite low, distance to the healthcare facility and the cost of transport were cited as barriers to uptake of postnatal care at a health facility.

Women beneficiaries of the community level integrated maternal health intervention were more likely to take up postnatal care in a health facility than their counterparts in the control. Similar findings were found in a study assessing the effect of an integrated maternal health intervention on skilled provider's care for maternal health in remote rural areas of Bangladesh. The comparative analysis between the baseline and end line surveys, performed separately for all of the performing areas, revealed that the intervention improved the use of skilled care during postnatal care in all the areas.17

The intervention was largely effective due to the adoption of a grassroots approach, utilizing CHWs/CHEWs and CHVs in their community units. Similarly, in a study assessing the effectiveness of a Community Health Worker “CHW” Program in Rural Kenya in improving maternal and newborn health, the number of women delivering under skilled attendance was higher for those mothers who reported exposure to one or more health messages, compared to those who did not. The delivery of health messages by CHWs increased knowledge of maternal and newborn care among women in the local community and encouraged deliveries under skilled attendance.18 Similarly, among the enabling characteristics, the counseling from a CHW, the HIV test results of the women's partner and the women's trust in the health system were associated with postnatal care use.19

In this study, women's education level was not associated with the uptake of postnatal care at a healthcare facility. This is contrary to the results from a study performed in Tanzania. In this study, it was found that factors such as women having received primary or higher education, whether the women had a cesarean section or forceps delivery, and women receiving counseling by a community health worker to uptake postnatal care at a healthcare facility, were positively correlated with the women uptaking postnatal care.19

The study found that distance was associated with healthcare facility use for postnatal care, which is in agreement with other studies that have been performed.20-22 Those who took between 30 minutes to 1 hour to get to a healthcare facility in our study were 6 times less likely to utilize postnatal care services. More specifically, it was found that women living in Mvomero Kilosa and Ulanga were less likely to receive postnatal care at a facility than those living in Morogoro DC.19 Accessibility to a health facility and their distribution within in a region is vital in determining the uptake of services. This was in agreement with a Tanzanian study, where the only community level variable associated with significant likelihood of receiving postnatal care was the geographic location of the respondent.

Through this study, it was found that factors such as healthcare workers educating women, the CHW referring women to a healthcare facility for postnatal care, and a commute of 30 minutes to 1 hour to reach a health care facility, were the determinants for women uptaking postnatal care services. These findings agree with the results from a review study, which identified twenty determinants grouped under four themes: (1) sociocultural factors, (2 perceived benefit/need of skilled attendants, (3) economic accessibility, and (4) physical accessibility.19,23

Limitations

A string of healthcare worker labor unrest, on and off from 2013 to 2017, may have possibly affected the optimal effect of this intervention. The study adopted a quasi experimental design; this has its inherent limitations, as more robust designs could have been used. This study focused on unique gaps in the Migori region in Kenya; hence, the intervention may not be representative of the entire population of the country.

Recommendation for Further Studies

There is a need to undertake similar community level maternal health interventions and evaluation at a larger scale, so as to determine whether the intervention effects will be observed at a large scale. In addition, it is important to implement more robust study designs, such as randomized trials to test the effectiveness of the same intervention within the general population with a greater precision. Further studies are needed to correlate maternal-infant outcomes and uptake of postnatal care among rural communities.

Conclusion and Implications for Translation

The intervention was largely effective in improving uptake of postnatal care due to the adoption of a grassroots approach, through the utilization of CHWs/CHEWs and CHVs within their community units. Women receiving health education by trained providers at healthcare facilities, coupled with CHWs' involvement in sensitization led to improved uptake of postnatal care. Ignorance and accessibility challenges were identified as barriers to uptake of postnatal care. The findings from this study will inform the county government of Migori, Kenya to focus on the specific factors identified as determinants to postnatal care uptake to ultimately improve it, and as such, improve the welfare of mothers and children. More so, this approach can be exploited, albeit with modifications, to suit other regions faced with low uptake of postnatal care.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declam no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure:

There are no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval:

Scientific and ethical approval to conduct this study was obtained from the Kenyatta University Ethical Review Committee (KUERC) - Application number PKU/487/E41.

Disclaimer:

None

Acknowledgments:

We acknowledge the contribution of Maternal and Infant Survival and Health care Advancement (MAISHA) team at Dedan Kimathi University of Technology (DeKUT) and College of The Rockies (COTR) - Canada, the Migori County healthcare team, and the Ministry of Health Kenya, among others for their outstanding contribution and support in ensuring success of this study.

Funding/Support:

The MAISHA project, on which this study was anchored, was funded by the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFTID), Canada.

References

- Evidence from district level inputs to improve quality of care for maternal and newborn health: interventions and findings. Reprod Health. 2014;11(Supp1 2(Suppl 2)):S3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trends in Maternal Mortality 1990-2010: WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank Estimates. World Health Organization; 2012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Continuum of care in maternal, newborn and child health in Pakistan: analysis of trends and determinants from 2006 to 20I2. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):189.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008-09. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2010.

- Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; 2015.

- Projahnmo Study Group. Effect of community-based newborn-care intervention package implemented through two service-delivery strategies in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9628):1936-1944.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improvement of perinatal and newborn care in rural Pakistan through community-based strategies: a cluster-randomised effectiveness trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9763):403-412.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of quality improvement in health facilities and community mobilization through women's groups on maternal, neonatal and perinatal mortality in three districts of Malawi: MaiKhanda, a cluster randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Int Health. 2013;5(3):180-195.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global perinatal health: accelerating progress through innovations, interactions, and interconnections. Semin Perinatol. 2010;34(6):367-370.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Exclusive breastfeeding promotion by peer counsellors in sub-Saharan Africa (PROMISE-EBF): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9789):420-427.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a package of community based maternal and newborn interventions in Mirzapur, Bangladesh. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9696.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Developing community-based intervention strategies to save newborn lives: Lessons learned from formative research in five countries. J Perinatol. 2008;28(Suppl 2):S2-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improving Newborn survival in low-income countries: community-based approaches and lessons from South Asia. PLoS Med. 2010;7(4):e1000246.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of women's groups and volunteer peer counselling on rates of mortality, morbidity, and health behaviours in mothers and children in rural Malawi (MaiMwana): a factorial, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9879):1721-1735.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Which intervention design factors influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? A systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(9):1207-1227.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drivers and deterrents of facility delivery in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2013;10:40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of an integrated maternal health intervention on skilled provider's care for maternal health in remote rural areas of Bangladesh: a pre and post study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:104.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improving maternal and newborn health: effectiveness of a community health worker program in rural Kenya. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104027.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of postnatal care use at health facilities in rural Tanzania: multilevel analysis of a household survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:282.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Contextual influences on the use of health facilities for childbirth in Africa. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(1):84-93.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barriers to the utilization of maternal health care in rural Mali. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(8):1666-82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of the physical accessibility of maternal health services on their use in rural Haiti. Popul Stud (Camb). 2006;60(3):271-88.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Still too far to walk: literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:34.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]