Translate this page into:

Promoting Health Literacy as an Important Initiative in Reducing Health Disparities and Advancing Health Equity

*Corresponding author: Gopal K. Singh, PhD, MS, MSc, DPS, The Center for Global Health and Health Policy, Global Health and Education Projects, Inc., Riverdale, MD, USA. Tel: +1-301-443-0765 gsingh@mchandaids.org

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Singh GK, Lee H, Kim LH, Daus GP. Promoting health literacy as an important initiative in reducing health disparities and advancing health equity. Int J Transl Med Res Public Health. 2024;8:e008. doi: 10.25259/IJTMRPH_58_2024

Abstract

Health literacy is increasingly being recognized as an important social determinant of health and a key initiative to reduce health disparities and promote health equity at global, national, regional, and local levels. We provide new definitions of health literacy covering both personal and organizational aspects. Individuals’ ability to use health information rather than just understand it in order to make informed decisions about their health and health care are the hallmarks of these definitions. The new definitions acknowledge the importance of organizations addressing health literacy themselves as patients should not be solely responsible for health literacy. Our analyses of two recent US databases, the 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the 2022 Health Center Patient Survey, show striking racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health literacy levels and consequent health impacts. Compared to White Americans, Asians, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics have markedly lower levels of health literacy as they experience greater difficulties in obtaining health information, understanding written health information, and information they receive from healthcare providers. Education and income gradients in health literacy are steep. Americans in the lowest education and income strata have 7 to 10 times greater difficulty in receiving needed medical advice or health information than those at the highest education and income levels; they score 17–20 points lower on the health literacy index than their counterparts with high education or income levels. Patients who do not receive easy-to-understand health information from their healthcare providers have significantly increased risks of poor health, serious psychological distress, and emergency care. We discuss social and health benefits and strategies for improving health literacy.

Keywords

Health Literacy

Social Determinants

Health Disparities

Health Equity

Health Information

Health Outcome

Race and Ethnicity

Socioeconomic Status

Health literacy is considered as an important social determinant of health and a key initiative to reduce health disparities and to promote health equity at global, national, regional, and local levels.[1,2]

Healthy People 2030, a national strategy for disease prevention and health promotion in the United States (US), uses new definitions of health literacy covering both personal and organizational aspects. Individuals’ ability to use health information rather than just understand it in order to make informed decisions about their health and health care and the acknowledgment that both individuals and organizations have a responsibility to address health literacy are the essential features of these definitions.[1] Specifically, personal health literacy is defined as the degree to which individuals can find, comprehend, and utilize information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.[1] Organizational health literacy, on the other hand, is defined as the extent to which organizations equitably enable individuals to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.[1]

More than 90 million people in the US have low health literacy, including the elderly, individuals with low socioeconomic position, non-native English speakers and individuals with limited English proficiency, immigrants, racial and ethnic minorities, individuals on publicly-funded health insurance, and people living in socioeconomically disadvantaged and medically underserved communities.[1,3,4] Individuals with low health literacy have poor health and healthcare outcomes, including higher risks of hospitalizations, greater numbers of emergency department visits, lower rates of cancer screening and immunization, difficulties in understanding health information and communications, limited knowledge of diseases, and lower medication compliance, all of which can contribute to higher risks of morbidity and mortality, increased healthcare costs, and health inequities.[1,3,4]

Our analysis of the Centers for Disease and Prevention’s (CDC’s) 2016 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS)[5] is shown in Table 1. More than 5.1% of US adults aged ≥18 years reported difficulties getting advice or information about health or medical topics if they need it; 7.4% reported difficulties understanding information that doctors, nurses, and other health professionals tell them; and 7.2% reported difficulties understanding written health information. Ethnic minorities such as Asians, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics in particular experience greater difficulties in obtaining health information, understanding written health information, and information they receive from healthcare providers. Hispanics, for example, score 12.0 points lower on the health literacy index than non-Hispanic Whites. Nearly 16.9% of Hispanics have difficulty understanding healthcare information from healthcare providers, compared with 6.2% of non-Hispanic Whites.

| Covariates | Difficult to get health/medical information N=79,990 | Difficult to understand information from health care professionals N=84,766 | Difficult to understand written health information N=79,665 | Difficult to get health/medical information N=79,990 | Difficult to understand information from health care professionals N=84,766 | Difficult to understand written health information N=79,665 | Health Literacy Index Score (low to high literacy) N=76,031 | Health Literacy Index Score (low to high literacy) N=76,031 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Unadjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Adjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||||||||||

| Prevalence | SE | Prevalence | SE | Prevalence | SE | aOR1 | 95% CI | aOR1 | 95% CI | aOR1 | 95% CI | Mean | SE | Mean1 | SE | ||||

| Total population | 5.12 | 0.14 | 7.43 | 0.17 | 7.16 | 0.17 | 100.00 | 0.13 | 100.00 | 0.13 | |||||||||

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 5.03 | 0.45 | 6.18 | 0.50 | 6.05 | 0.54 | 1.14 | 0.80 | 1.63 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 98.57 | 0.42 | 100.05 | 0.57 | ||

| 25–34 | 6.04 | 0.45 | 7.08 | 0.48 | 6.53 | 0.47 | 1.47 | 1.10 | 1.97 | 1.26 | 0.99 | 1.61 | 1.15 | 0.88 | 1.50 | 99.33 | 0.39 | 98.78 | 0.40 |

| 35–44 | 6.05 | 0.44 | 7.61 | 0.48 | 6.52 | 0.42 | 1.61 | 1.23 | 2.11 | 1.37 | 1.06 | 1.76 | 1.12 | 0.85 | 1.48 | 99.90 | 0.36 | 99.00 | 0.34 |

| 45–54 | 5.60 | 0.35 | 8.51 | 0.42 | 8.01 | 0.41 | 1.60 | 1.26 | 2.03 | 1.53 | 1.19 | 1.96 | 1.40 | 1.07 | 1.75 | 98.80 | 0.32 | 97.90 | 0.32 |

| 55–64 | 4.90 | 0.29 | 7.70 | 0.37 | 8.56 | 0.40 | 1.31 | 1.06 | 1.62 | 1.20 | 0.92 | 1.56 | 1.32 | 1.00 | 1.75 | 98.99 | 0.30 | 98.93 | 0.29 |

| ≥65 | 3.56 | 0.20 | 7.13 | 0.30 | 8.97 | 0.36 | 1.00 | reference | 1.15 | 0.87 | 1.54 | 1.32 | 0.97 | 1.79 | 98.31 | 0.23 | 99.41 | 0.34 | |

| Gender | |||||||||||||||||||

| Male | 5.28 | 0.22 | 8.03 | 0.26 | 8.65 | 0.28 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 97.85 | 0.20 | 97.63 | 0.20 | |||

| Female | 4.97 | 0.19 | 6.88 | 0.22 | 6.69 | 0.22 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 1.01 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.75 | 99.94 | 0.18 | 100.14 | 0.17 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 3.84 | 0.14 | 6.18 | 0.18 | 6.38 | 0.18 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 100.21 | 0.14 | 99.17 | 0.16 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 5.87 | 0.38 | 7.80 | 0.41 | 8.65 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.77 | 1.03 | 99.00 | 0.33 | 101.49 | 0.33 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 6.80 | 1.22 | 10.09 | 1.60 | 9.90 | 1.67 | 0.91 | 0.60 | 1.38 | 0.97 | 0.66 | 1.42 | 0.94 | 0.65 | 1.35 | 96.92 | 1.39 | 100.21 | 1.25 |

| Asian | 7.07 | 1.15 | 9.48 | 1.28 | 8.61 | 1.34 | 2.54 | 1.74 | 3.71 | 2.46 | 1.80 | 3.37 | 2.41 | 1.68 | 3.46 | 94.78 | 1.09 | 91.77 | 1.04 |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 10.60 | 5.16 | 9.91 | 4.71 | 13.75 | 5.47 | 2.79 | 0.96 | 8.06 | 2.09 | 0.76 | 5.72 | 3.05 | 1.26 | 7.39 | 95.32 | 4.31 | 94.09 | 4.04 |

| Other and multiple race | 7.49 | 1.33 | 8.31 | 1.22 | 6.74 | 1.11 | 1.41 | 0.95 | 2.11 | 1.10 | 0.79 | 1.53 | 0.87 | 0.62 | 1.22 | 99.97 | 1.07 | 100.53 | 1.03 |

| Hispanic | 13.94 | 1.00 | 16.89 | 1.09 | 16.53 | 1.13 | 2.08 | 1.69 | 2.57 | 1.81 | 1.49 | 2.21 | 1.75 | 1.44 | 2.14 | 88.21 | 0.77 | 92.79 | 0.71 |

| LGB status | |||||||||||||||||||

| Straight/heterosexual | 4.84 | 0.17 | 6.92 | 0.20 | 7.05 | 0.21 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 99.30 | 0.16 | 98.93 | 0.17 | |||

| Lesbian/Gay | 6.23 | 1.48 | 9.39 | 2.30 | 6.63 | 1.76 | 1.10 | 0.62 | 1.96 | 1.39 | 0.87 | 2.23 | 1.05 | 0.63 | 1.78 | 100.47 | 1.24 | 100.10 | 1.11 |

| Bisexual | 7.72 | 1.50 | 12.33 | 2.27 | 11.48 | 2.25 | 1.09 | 0.69 | 1.70 | 1.60 | 1.05 | 2.45 | 1.56 | 0.97 | 2.51 | 94.46 | 1.57 | 96.41 | 1.41 |

| Other | 22.59 | 5.40 | 24.18 | 5.46 | 16.71 | 4.72 | 2.54 | 1.40 | 4.60 | 2.04 | 1.02 | 4.07 | 1.11 | 0.51 | 2.39 | 84.88 | 3.91 | 93.63 | 3.99 |

| Unknown | 5.44 | 0.26 | 8.20 | 0.31 | 8.87 | 0.33 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.25 | 98.41 | 0.25 | 99.23 | 0.26 |

| Marital status | |||||||||||||||||||

| Married | 3.50 | 0.17 | 6.07 | 0.21 | 6.10 | 0.22 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 100.86 | 0.16 | 99.18 | 0.19 | |||

| Widowed | 5.30 | 0.45 | 8.79 | 0.53 | 11.22 | 0.64 | 1.06 | 0.85 | 1.33 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 1.06 | 1.07 | 0.89 | 1.27 | 95.62 | 0.49 | 98.80 | 0.51 |

| Divorced/separated | 7.64 | 0.45 | 10.57 | 0.52 | 10.90 | 0.53 | 1.09 | 0.91 | 1.31 | 0.99 | 0.86 | 1.15 | 1.11 | 0.96 | 1.28 | 96.05 | 0.40 | 98.67 | 0.37 |

| Single | 6.98 | 0.35 | 8.07 | 0.37 | 8.00 | 0.38 | 1.22 | 1.02 | 1.46 | 0.94 | 0.80 | 1.10 | 1.05 | 0.89 | 1.22 | 97.57 | 0.3 | 98.74 | 0.34 |

| Geographic region | |||||||||||||||||||

| Northeast | 3.35 | 0.32 | 7.16 | 0.50 | 7.15 | 0.50 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 99.64 | 0.37 | 99.68 | 0.41 | |||

| Midwest | 4.97 | 0.27 | 6.99 | 0.30 | 7.30 | 0.32 | 1.83 | 1.42 | 2.37 | 1.07 | 0.88 | 1.30 | 1.11 | 0.91 | 1.35 | 98.80 | 0.24 | 97.96 | 0.24 |

| South | 5.72 | 0.20 | 7.79 | 0.22 | 7.95 | 0.23 | 1.82 | 1.45 | 2.29 | 1.02 | 0.85 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 98.87 | 0.18 | 99.34 | 0.18 |

| West | 6.37 | 0.89 | 6.76 | 0.79 | 7.12 | 0.89 | 2.93 | 1.94 | 4.43 | 1.17 | 0.84 | 1.61 | 1.13 | 0.80 | 1.60 | 98.02 | 0.73 | 96.83 | 0.75 |

| Metropolitan status | |||||||||||||||||||

| Metropolitan area | 4.17 | 0.25 | 6.63 | 0.31 | 7.21 | 0.33 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 99.97 | 0.23 | 99.00 | 0.25 | |||

| Nonmetropolitan area | 5.42 | 0.43 | 8.26 | 0.52 | 8.44 | 0.48 | 1.01 | 0.81 | 1.25 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 1.18 | 0.91 | 0.77 | 1.07 | 96.70 | 0.41 | 97.97 | 0.40 |

| Education (years of school completed) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Less than high school (<12) | 13.79 | 0.74 | 20.35 | 0.84 | 22.13 | 0.91 | 2.06 | 1.64 | 2.58 | 3.30 | 2.74 | 3.97 | 4.16 | 3.39 | 5.09 | 85.17 | 0.64 | 90.68 | 0.62 |

| High school (12) | 5.72 | 0.27 | 8.52 | 0.31 | 9.18 | 0.33 | 1.44 | 1.19 | 1.75 | 1.91 | 1.64 | 2.23 | 2.32 | 1.95 | 2.75 | 96.12 | 0.25 | 97.22 | 0.24 |

| Some college (13-15) | 3.72 | 0.21 | 4.61 | 0.21 | 4.72 | 0.23 | 1.18 | 0.97 | 1.43 | 1.23 | 1.05 | 1.44 | 1.46 | 1.23 | 1.74 | 101.40 | 0.20 | 100.64 | 0.21 |

| College degree or higher (≥16) | 2.06 | 0.14 | 2.88 | 0.17 | 2.63 | 0.17 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 105.03 | 0.16 | 102.41 | 0.20 | |||

| Household income ($) | |||||||||||||||||||

| <10,000 | 15.57 | 1.18 | 16.97 | 1.17 | 17.96 | 1.25 | 3.74 | 2.72 | 5.15 | 2.47 | 1.90 | 3.20 | 1.98 | 1.50 | 2.64 | 87.74 | 0.90 | 94.26 | 0.87 |

| 10,000–19,999 | 11.13 | 0.63 | 14.84 | 0.70 | 14.54 | 0.69 | 3.09 | 2.32 | 4.12 | 2.46 | 2.00 | 3.01 | 1.76 | 1.39 | 2.22 | 91.38 | 0.51 | 96.58 | 0.50 |

| 20,000–24,999 | 9.46 | 0.71 | 11.79 | 0.74 | 11.92 | 0.75 | 3.21 | 2.42 | 4.26 | 2.34 | 1.90 | 2.88 | 1.81 | 1.42 | 2.30 | 93.75 | 0.52 | 96.70 | 0.49 |

| 25,000–34,999 | 5.68 | 0.51 | 8.71 | 0.67 | 9.13 | 0.69 | 2.30 | 1.71 | 3.08 | 1.99 | 1.60 | 2.47 | 1.59 | 1.25 | 2.03 | 97.35 | 0.47 | 98.57 | 0.46 |

| 35,000–49,999 | 4.06 | 0.39 | 5.43 | 0.42 | 5.82 | 0.42 | 1.95 | 1.47 | 2.58 | 1.45 | 1.17 | 1.79 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 1.59 | 99.51 | 0.35 | 99.05 | 0.36 |

| 50,000–74,999 | 2.07 | 0.26 | 4.27 | 0.34 | 4.13 | 0.32 | 1.18 | 0.86 | 1.62 | 1.37 | 1.11 | 1.70 | 1.10 | 0.88 | 1.39 | 102.02 | 0.28 | 99.99 | 0.29 |

| ≥75,000 | 1.57 | 0.15 | 2.76 | 0.18 | 3.06 | 0.23 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 104.69 | 0.18 | 101.48 | 0.24 | |||

| Unknown | 5.72 | 0.38 | 9.42 | 0.49 | 10.29 | 0.53 | 2.30 | 1.77 | 2.99 | 2.21 | 1.83 | 2.67 | 1.89 | 1.52 | 2.35 | 96.18 | 0.41 | 97.14 | 0.38 |

| Housing tenure | |||||||||||||||||||

| Homeowner | 3.56 | 0.15 | 6.21 | 0.19 | 6.47 | 0.19 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 100.41 | 0.15 | 99.27 | 0.18 | |||

| Renter | 9.24 | 0.35 | 10.57 | 0.36 | 10.71 | 0.38 | 1.44 | 1.24 | 1.67 | 1.07 | 0.95 | 1.22 | 1.12 | 0.98 | 1.28 | 95.06 | 0.28 | 98.05 | 0.30 |

| Employment status | |||||||||||||||||||

| Employed | 4.05 | 0.18 | 5.78 | 0.20 | 5.49 | 0.21 | 1.21 | 0.97 | 1.51 | 1.17 | 0.98 | 1.40 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 1.17 | 101.05 | 0.17 | 99.48 | 0.19 |

| Not employed | 11.48 | 1.03 | 12.30 | 1.06 | 11.62 | 0.99 | 1.76 | 1.31 | 2.37 | 1.42 | 1.09 | 1.85 | 1.23 | 0.94 | 1.60 | 93.57 | 0.79 | 97.53 | 0.76 |

| Homemaker | 6.93 | 0.75 | 8.21 | 0.84 | 9.99 | 0.87 | 1.47 | 1.08 | 1.99 | 1.08 | 0.83 | 1.41 | 1.33 | 1.04 | 1.69 | 96.95 | 0.64 | 98.37 | 0.60 |

| Student | 3.94 | 0.51 | 5.92 | 0.74 | 4.38 | 0.69 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 1.51 | 1.39 | 0.97 | 1.98 | 0.79 | 0.52 | 1.20 | 99.37 | 0.60 | 99.06 | 0.70 |

| Retired | 3.22 | 0.21 | 6.32 | 0.31 | 8.10 | 0.37 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 99.03 | 0.24 | 99.60 | 0.34 | |||

| Uanble to work | 13.13 | 0.75 | 19.69 | 0.88 | 20.62 | 0.91 | 1.49 | 1.18 | 1.89 | 1.68 | 1.39 | 2.03 | 1.64 | 1.37 | 1.98 | 87.23 | 0.64 | 94.50 | 0.63 |

| Activity limitation | |||||||||||||||||||

| Limited | 9.37 | 0.51 | 13.73 | 0.58 | 13.59 | 0.58 | 1.75 | 1.46 | 2.10 | 1.76 | 1.53 | 2.02 | 1.53 | 1.33 | 1.75 | 93.28 | 0.42 | 96.50 | 0.40 |

| Not limited | 4.19 | 0.20 | 5.89 | 0.22 | 6.32 | 0.24 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 100.23 | 0.18 | 99.65 | 0.20 | |||

| Emotional or social support | |||||||||||||||||||

| Rarely/never (low support) | 14.03 | 2.05 | 16.54 | 1.68 | 15.39 | 1.62 | 3.82 | 2.32 | 6.28 | 2.46 | 1.76 | 3.45 | 1.98 | 1.46 | 2.69 | 89.82 | 1.20 | 95.98 | 2.82 |

| Sometimes | 10.29 | 1.15 | 16.53 | 1.84 | 15.15 | 1.66 | 2.86 | 1.91 | 4.28 | 2.70 | 2.00 | 3.64 | 2.19 | 1.62 | 2.97 | 90.56 | 1.16 | 95.38 | 2.83 |

| Usually | 3.78 | 0.51 | 5.69 | 0.63 | 6.02 | 0.59 | 2.37 | 1.64 | 3.44 | 1.79 | 1.35 | 2.37 | 1.62 | 1.26 | 2.09 | 98.53 | 0.50 | 97.74 | 2.72 |

| Always (high support) | 1.77 | 0.22 | 3.75 | 0.29 | 4.56 | 0.32 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 103.98 | 0.28 | 103.90 | 2.65 | |||

| Life satisfaction | |||||||||||||||||||

| Satisfied with life | 3.15 | 0.22 | 5.71 | 0.31 | 6.29 | 0.32 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 100.90 | 0.26 | 98.49 | 2.65 | |||

| Dissatisfied with life | 21.25 | 2.86 | 26.31 | 3.13 | 20.11 | 2.20 | 2.29 | 1.45 | 3.62 | 1.97 | 1.38 | 2.82 | 1.45 | 1.04 | 2.01 | 84.85 | 1.79 | 92.65 | 3.07 |

| Internet use | |||||||||||||||||||

| Yes | 4.07 | 0.14 | 5.66 | 0.17 | 5.42 | 0.16 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 100.80 | 0.13 | 99.73 | 0.15 | |||

| No | 10.37 | 0.48 | 15.50 | 0.54 | 18.34 | 0.61 | 1.59 | 1.36 | 1.86 | 1.56 | 1.36 | 1.79 | 1.77 | 1.56 | 2.01 | 89.38 | 0.41 | 94.97 | 0.43 |

| Physical activity | |||||||||||||||||||

| Not active | 8.26 | 0.37 | 11.83 | 0.42 | 11.81 | 0.43 | 1.24 | 1.08 | 1.42 | 1.25 | 1.12 | 1.40 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.26 | 94.27 | 0.32 | 97.82 | 0.30 |

| Physically active | 4.10 | 0.15 | 5.96 | 0.18 | 6.27 | 0.18 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 100.43 | 0.14 | 99.32 | 0.15 | |||

| Smoking status | |||||||||||||||||||

| Current smoker | 9.27 | 0.45 | 12.04 | 0.51 | 11.43 | 0.51 | 1.47 | 1.27 | 1.71 | 1.30 | 1.14 | 1.48 | 1.16 | 1.01 | 1.33 | 94.82 | 0.38 | 98.00 | 0.36 |

| Former smoker | 4.07 | 0.25 | 6.65 | 0.31 | 7.23 | 0.32 | 1.06 | 0.89 | 1.25 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 1.12 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 1.06 | 99.66 | 0.24 | 99.53 | 0.24 |

| Non-smoker | 4.28 | 0.18 | 6.32 | 0.21 | 6.60 | 0.22 | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 1.00 | reference | 99.92 | 0.17 | 99.02 | 0.17 | |||

Notes: SE = standard error; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Chi-square statistics for testing the overall association between each covariate and health literacy outcome variables were statistically significant at P < 0.01. Health literacy Index (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.68; mean =100; standard deviation = 20) was constructed by factor analyzing three variables, difficult to get health/medical information (factor loading = 0.66), difficult to understand information from healthcare professionals (factor loading = 0.85), and difficult to understand written health information (factor loading = 0.84). 1Odds ratios were adjusted by logistic regression and mean health literacy index scores were adjusted by weighted least squares regression for age, race/ethnicity, gender, LGB status, marital status, region and place of residence, education, household income, housing tenure, employment status, activity limitation, social support, life satisfaction, internet use, physical activity, and smoking status. Multiple R-Square for Health Literacy Index was 14.39.

Older adults aged 65 and older have the lowest score on the health literacy index and report greater difficulties in understanding health information, particularly written information, than individuals of younger ages (18–24 years vs. ≥65 years: 6.1% vs. 9.0%). Men, on average, have significantly lower levels of health literacy and are more likely to experience difficulties in receiving and understanding health information than women. Education and income gradients in the health literacy measures are quite steep. Adults in the lowest education and income strata have 7 to 10 times greater difficulty in receiving needed medical advice or health information than those at the highest education and income levels – and they score 17–20 points lower on the health literacy index than their high education or income counterparts.

Additionally, adults who report higher levels of dissatisfaction with life, activity limitation, physical inactivity, and smoking, and lower levels of social support and internet use are significantly more likely to report lower levels of health literacy. Non-metropolitan area (rural) residents experience greater difficulties in receiving and understanding health information than metropolitan area (urban) residents.

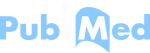

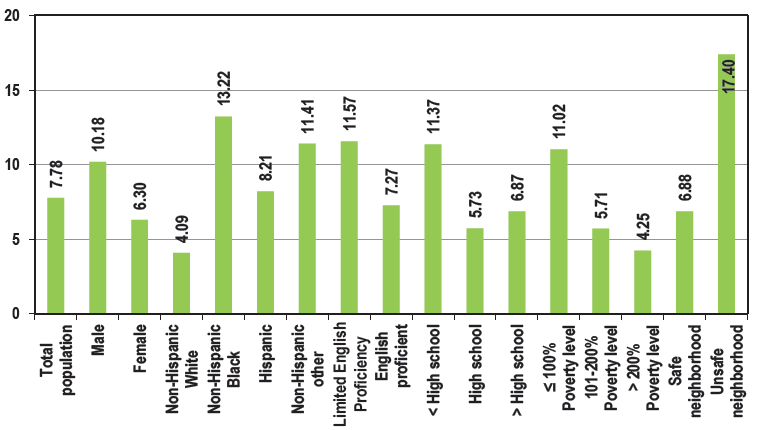

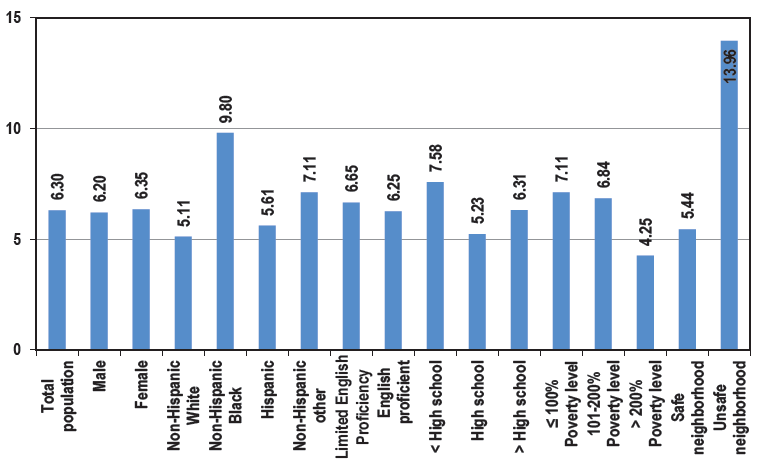

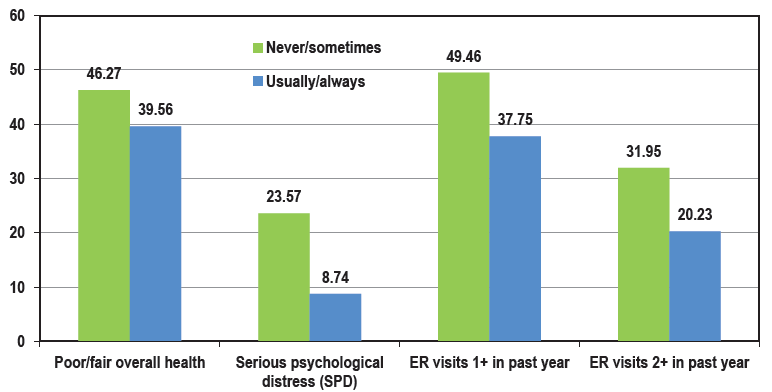

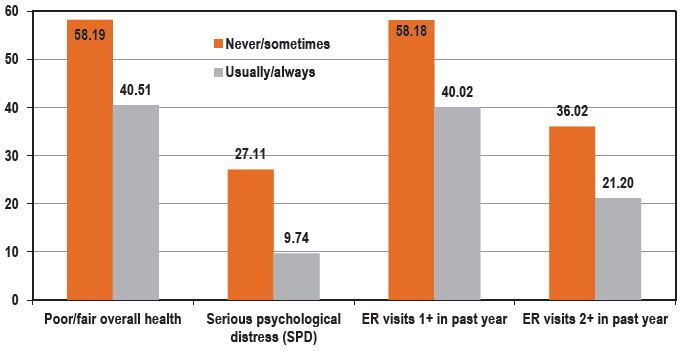

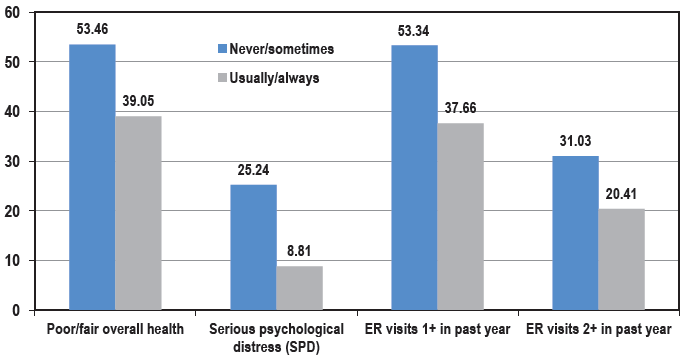

Our analysis of the 2022 Health Center Patient Survey (HCPS)[6] provides additional findings on health literacy among patients who receive comprehensive primary and preventive healthcare services through the Health Center Program administered by the US Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). While the BRFSS analysis above is focused on characteristics associated with personal health literacy, the HCPS data provide an opportunity to evaluate several aspects of organizational health literacy, such as provider–patient communication, quality of care, and satisfaction with healthcare services. For example, Black, Hispanic, and other patients (comprising mostly of Asian/Pacific Islander and American Indian and Alaska Native patients) are 2–3 times more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to report that their doctors or healthcare providers do not explain things in an easy-to-understand manner [Figure 1a]. Patients living below the federal poverty level (FPL) are more than twice as likely to not receive adequate explanations from their healthcare providers than those with incomes above 100% FPL. Patients living in unsafe neighborhoods are 2.5 times more likely to report not receiving adequate explanations from their healthcare providers than those living in safe neighborhoods. Similar racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities are seen among patients not receiving easy-to-understand health information from providers [Figure 1b] or being carefully listened to by providers [Figure 1c]. Consistent with the empirical literature, health center patients who do not receive adequate explanations or easy-to-understand health information and are not being carefully listened to by their healthcare providers are at significantly increased risks of poor overall health, serious psychological distress, and emergency care [Figure 1d-f].

- Social Determinants and Health Impacts of Low Health Literacy, 2022 US Health Center Patient Survey (N = 3,970). Doctor or other health professional does not usually or always explain things in easy-to-understand manner (%).

- Social Determinants and Health Impacts of Low Health Literacy, 2022 US Health Center Patient Survey (N = 3,970). Doctor or other health professional does not usually or always give easy-to-understand information about health questions and concerns (%).

- Social Determinants and Health Impacts of Low Health Literacy, 2022 US Health Center Patient Survey (N = 3,970). Doctor or other health professional does not usually or always listen carefully to patient (%).

- Social Determinants and Health Impacts of Low Health Literacy, 2022 US Health Center Patient Survey (N = 3,970). Health outcomes associated with healthcare professionals’ frequency of explaining things in easy-to-understand manner (%). ER: Emergency room.

- Social Determinants and Health Impacts of Low Health Literacy, 2022 US Health Center Patient Survey (N = 3,970). Health outcomes associated with healthcare professionals’ frequency of giving easy-to-understand information about health questions or concerns (%). ER: Emergency room.

- Social Determinants and Health Impacts of Low Health Literacy, 2022 US Health Center Patient Survey (N = 3,970). Health outcomes associated with healthcare professionals’ frequency of listening carefully to patients. ER: Emergency room.

In addition to BRFSS and HCPS, several other HHS databases[7] such as HRSA’s National Survey of Children’s Health, CDC’s National Health Interview Survey, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Health Literacy Patient Survey and Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, and National Cancer Institute’s National Health Information Trends Survey, cover several aspects of health literacy in the US either directly or indirectly.

Health literacy is a major priority for the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as it serves as a common thread running across many HHS programs that serve racial and ethnic minorities, poor, socially disadvantaged, and medically underserved populations.[1,8–10] There is clearly a need to meet the health needs of the most disadvantaged and marginalized populations and communities – and improving health literacy can serve as a critical resource.[1,2,9,10] A consensus set of definitions, measures, recommendations, and strategies for improving health literacy at personal and organizational levels will allow both public- and private-sector programs to implement policies and practices that advance progress in reducing inequities in health and well-being of the populations that they serve.[1,2,9,10]

Poor health literacy is a problem not only in the US, but is also an understated public health issue globally.[11] In 2006, only about 12% of US adults were considered proficient in health literacy,[9] while nearly half of European adults in 2015 reported having problems with health literacy and not having relevant capabilities enabling them to take care of their health and that of others.[11,12] Based on 2006–2015 data from Demographic and Health Surveys in 14 Sub-Saharan African countries, health literacy varied greatly between countries, from 8.5% in Niger to 63.9% in Namibia.[13]

There are several strategies for improving health literacy. From a healthcare systems and organizational perspective, these strategies may include (1) training healthcare providers to provide accurate and easy-to-understand information to patients, including care instructions, pamphlets, clear signage and directions to doctors’ offices and healthcare facilities, (2) offering language assistance at without cost to patients with limited English proficiency, (3) recruiting and retaining a diverse healthcare workforce that provides culturally and linguistically appropriate health information services to the population in their community, (4) using easy-to-complete forms and telephone or other communication systems that are patient-friendly, and (5) involving patients, the public, and communities in all aspects of health and social care.[1,8,10,14,15] Evidence-based resources exist to help organizations improve health literacy.[16] Additional research is needed to better understand the links between health and language literacy and health outcomes and to address the role of health literacy as a key social determinant of health and health equity.[1,2]

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Gopal Singh is the Editor-in-Chief of the journal. He did not participate in the adjudication of this article. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Financial Disclosure

None to report.

Funding/Support

None.

Ethics Approval

Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study, as it is based on the secondary analysis of two public-use federal databases.

Acknowledgments

None.

Declaration of Patient Consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for Manuscript Preparation

The author(s) confirms that there was no use of Artificial Intelligence (AI)-Assisted Technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using the AI.

Disclaimer

The views expressed are the authors’ and not necessarily those of their institutions.

REFERENCES

- Health Literacy in Healthy People 2030. https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/health-literacy-healthy-people-2030 and https://health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health/literature-summaries/health-literacy. Accessed July 19, 2024

- Health Literacy. https://www.who.int/teams/health-promotion/enhanced-wellbeing/ninth-global-conference/health-literacy. Accessed July 19, 2024.

- What is the meaning of health literacy? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Fam Med Community Health. 2020;8(2):e000351.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Health literacy and health outcomes of adults in the United States: implications for providers. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2018;16(4) Article 2

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2016: LLCP Codebook Report. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2016/pdf/codebook16_llcp.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2024

- Health Center Patient Survey. Bureau of Primary Health Care. 2023. https://bphc.hrsa.gov/data-reporting/health-center-patient-survey. Accessed July 19, 2024

- Health, United States 2020-2021: Annual Perspective. 2023. doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:12204

- Reducing health disparities through health literacy. US Office of Minority Health blog post. Published April 27, 2023. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/news/national-minority-health-month-2023-reducing-health-disparities-through-health-literacy. Accessed July 19, 2024.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National Action Plan to Improve Health. 2010. https://health.gov/our-work/national-health-initiatives/health-literacy/national-action-plan-improve-health-literacy. Accessed July 19, 2024

- COVID-19: health literacy is an underestimated problem. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e249-e250. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30086-4

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Health literacy in Europe: comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU) Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(6):1053-1058. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckv043

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Measurement of health literacy to advance global health research: a study based on Demographic and Health Surveys in 14 sub-Saharan countries. Lancet Global Health. 2017;18 Published online April 7

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Listening to patients at all levels of health care. BMJ. 2024;386:q1523. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.q1523

- [Google Scholar]

- Health Literacy: A Key to Good Health. 2021. https://www.samhsa.gov/blog/health-literacy-key-good-health. Accessed July 19, 2024

- AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit: Third Edition. 2024. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/index.html. Accessed July 19, 2024