Translate this page into:

The Mental Health of Syrian Refugees in the United States: Examining Critical Risk Factors and Major Barriers to Mental Health Care Access

Abstract

Owing to the 2011 civil war, many Syrians have become displaced internally within the country, have fled to neighboring countries in the region, or have resettled as refugees in the United States (US) through the United States Resettlement Program (USRP). Few studies have been conducted on the mental health of adult Syrian refugees in the US. We conducted an ecological study on the relationship between the mental health status of Syrian refugees in the US, risk factors that negatively affect their mental health post-settlement, and the barriers that prevent them from seeking mental health care. We found that racialization, targeting, under-employment, and concerns about relatives still in Syria negatively affect the mental health of Syrian refugees post-settlement. Challenges with the English language, stigma, lack of access to adequate insurance and transportation, and poor health system acculturation were barriers to Syrian refugee mental health care-seeking behavior in the US. While the US is accepting and resettling Syrian refugees in various parts of the country, it is also important that it focuses on and invests in the mental health needs of the refugees, so as to improve their physical and mental well-being.

Keywords

Syrian Refugees

Mental Health

Mental Health Care Barriers

United States

Introduction

Mental health is not merely the absence of a mental disorder or infirmity but a complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being that allows individuals to cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively, and contribute meaningfully to society.1-3 Mental health is vital for emotional, psychological, and social well-being and determines how people handle stress, relate to others, and make decisions.4 There are various types of mental health disorders, and some are more complex than others. While the causes of most mental health disorders are not fully understood, a combination of biological, psychological, and environmental risk factors have been identified as contributing factors.5 The abnormal functioning of nerve cell circuits or pathways that connect particular brain regions, genetics, injury, infections, substance abuse, and chemical imbalances in the brain are biological risk factors that have been identified to affect mental health. These factors cause disorders such as autism and attention deficit disorder.6 Psychological factors affect a person's mood, thinking, and behavior. They contribute to mental health disorders such as anxiety, trauma, depression, schizophrenia, bipolar, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.7 Unlike biological and psychological factors, environmental factors are stressors that individuals experience on a daily basis. They include the lack of access to resources such as adequate housing, exposure to violence, the experience of death and displacement, feelings of inadequacy, and cultural disconnect.5,8 Environmental stressors may be physical or social.9 Physical environmental stressors may influence mental health by altering psychosocial processes and affecting a person's biology or neurochemistry.10 Social environmental stressors on the other hand are issues associated with the extended family or wider community such as violence, stigma, discord, abuse, poverty, and the lack of safety and a strong social support system that may affect mental health.11 Mental health disorders caused by environmental stressors include post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety.12

The violence civilians witness or experience during a war can affect their mental health and expose them to mental health disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression.13 Studies conducted on the effects of war on mental health among the general population by Murthy and Lopez et al., showed an increase in the incidence and prevalence of mental health disorders.14,15 In their study on mental disorders in conflict settings in 2019, Charlson et al. found that 22% of people living in conflict areas had depression, anxiety, PTSD, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia.16 In about 9% of that population, the mental health disorders were moderate to severe and in the remaining 13% of that population, was mild.16

War destroys communities and families and often disrupts the social and economic fabric of nations.14 The civil war in Syria has left many with mental health disorders, especially those living as refugees in countries elsewhere including the United States (US).17 In addition to the trauma they experienced in their home country due to the war, Syrian refugees resettled in the US experience risk factors such as racialization, targeting, the inability to find meaningful employment, and concern about relatives still in Syria, which further affect their mental health.18 Their inability to speak the English language, stigma, and the lack of access to adequate insurance and transportation, as well as poor health system acculturation serve as barriers to Syrian refugee resulting to lack of mental health care-seeking behavior in the US.

We conducted an ecological study on the relationship between the mental health status of adult Syrian refugees in the US, risk factors in the US that negatively affects their mental health post-settlement, and the barriers that prevent them from seeking mental health care. We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, and other credible search engines and reviewed 62 English articles related to the Syrian war, mental health of refugees, risk factors, and barriers to mental health-seeking behavior Published between 2012 and 2022. Forty-two were relevant to our study. Few studies have been conducted on the mental health of Syrian refugees in the US. This article focuses on the relationship between the mental health status of Syrian refugees in the US, risk factors in the US that negatively affects their mental health post-settlement, and the barriers that prevent them from seeking mental health care. It is important for the US to focus on and invests in the mental health needs of refugees as part of their resettlement process, so as to improve their physical and mental well-being

Mental Health of Syrian Refugees

Pre-Resettlement in the US

On March 2011, a peaceful pro-democracy demonstration took place in the southern Syrian city of Derra against the long-standing Assad dynastic regime.19 In response to the demonstration, the Assad regime unleashed extensive violence through its police, military, and paramilitary forces. This led to mass protests and the demand for the resignation of President Assad.19 As President Assad declined to resign, the protests escalated and spread to other parts of the country, and by 2012, a full-fledged civil war had broken out in Syria.19 As a result of the war, over 50% of the Syrian population (22 million) have fled from their homes: about 5.6 million are internally displaced within Syria, and an estimated 5.6 million have sought refuge in other countries including the US.20

As victims of one of the largest humanitarian disasters in recent times, Syrian refugees have paid a high price - they have suffered from various mental health disorders.21 According to a study conducted of 6,000 Syrian refugees by officials from the International Medical Corps in Syria, 31% of Syrians showed signs of severe emotional disorders due to the war and forced displacement, 20% of that population had anxiety, and 6% suffered from bipolar disorders.22

In their systematic review of 66 studies on the prevalence rate of mental health disorders among Syrians moving to high-income countries including the US as refugees, Henkelmann et al. reported a pooled prevalence of 29% and 37% for diagnosed and self-reported PTSD cases respectively, 30% and 40% for diagnosed and self-reported depression, and 13% and 42% for diagnosed and self-reported anxiety.23

Post-Settlement in the US

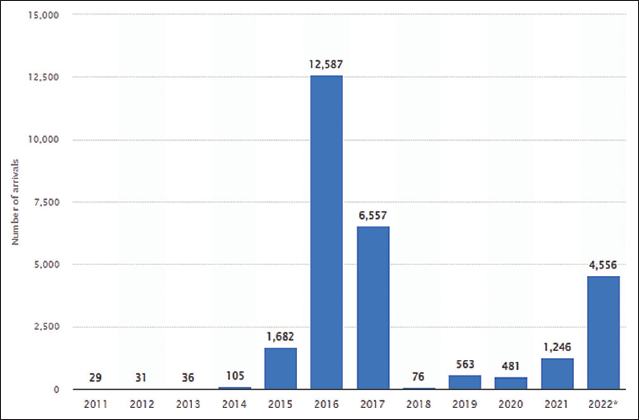

Resettlement is the selection and transfer of refugees from a country in which they have sought protection to a third country that has permitted them to stay based on long-term or permanent residence status.24 In the US, the resettlement process (Figure 1) is rigorous and can take up to two years. In 2022, 4,556 Syrian refugees were resettled in the US (Figure 2).25 Between 2012 and 2017, a total of 18,007 Syrian refugees were resettled across the US with major cities like San Diego (6%), Chicago (4%), and Troy (3%) accepting the most refugees (Table 1).26 About 72% of that population were children under the age of 14 and women.26 Ninety-eight percent were Muslim, 1% were Christian, 96% spoke Arabic, and about 3% spoke Kurdish.26

- US refugee resettlement process. Source: USA for UNHCR https://www.unrefugees.org/news/the-u-s-refugee-resettle-ment-program-explained/24

- Syrian Refugee arrivals in the US -2022 to September 30, 2022. Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/742553/syri-an-refugee-arrivals-us/25

| Metropolitan Area | Number | Share of Total (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 18,007 | 100 |

| San Diego, CA | 1,040 | 6 |

| Chicago, IL | 765 | 4 |

| Troy, MI | 594 | 3 |

| Glendale, AZ | 489 | 3 |

| Houston, TX | 447 | 2 |

| Dallas, TX | 437 | 2 |

| Clinton Township, MI | 428 | 2 |

| Atlanta, GA | 404 | 2 |

| Sacramento, CA | 380 | 2 |

| Dearborn, MI | 357 | 2 |

2017 data are for the first quarter of 2017. Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of data from the US Department of State's Refugee Processing Center, “Admissions & Arrivals” database.26

According to Almoshmosh, resettled Syrian refugees in high-income countries including the US, experience feelings of estrangement, loss of identity and disorientation, loss of role, and disturbance of social networks; these experiences cause anxiety, sadness, hyper-vigilance, social withdrawal, and flashbacks of recent trauma.27 A study of Syrian refugees resettling in the USA screened at primary care found a high prevalence of possible psychiatric disorders related to trauma and stress.16 In a survey conducted on the mental health of Syrian refugees resettled in Metropolitan Atlanta in 2017, M'zah et al. found high rates of anxiety (60%), depression (44%) and PTSD (84%) symptoms.28 In their study of 157 Syrian refugees in Detroit also in 2017, Javanbakht et al. found that many of the refugees had possible anxiety (40.3%) or depression (47.7%), with women more likely than men to have possible anxiety (52.7% vs. 29.7%) or depression (58.5% vs. 38.3%).16 They also found that about one-third of adult Syrian refugees (with no gender difference) who resettled in Detroit met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, and that the rates were comparable to PTSD rates documented in Vietnam war combat veterans.16

Post-Settlement Mental Health Risk Factors

Efforts to resettle Syrian refugees in the US focus primarily on providing basic necessities and core services. Consequently, no attention is paid to their mental health needs. As they enter the US, Syrian refugees already have mental health issues, and after they enter the country, they experience risk factors such as racialization, targeting, the inability to find meaningful employment, and concern about relatives still in Syria, which further affect their mental health.

Racialization and Targeting

Race in the US is a tool for classifying people into social groups.29 Thus, immigrants who arrive in the country are also racialized or incorporated into racial categories. Those from the West Indies are racialized as “Black,” and those from Spanish-speaking South American countries are racialized as “Latino/a” and “Hispanic.”30 Immigrants from Syria are legally classified as “White,” making their Arab ethnicity invisible as a distinct group. Irrespective of this classification, Syrian refugees in the US are subject to racism and targeting, which diminishes their sense of legal and physical security.31 While not all Syrian refugees are Muslims, they have become linked by perceived association with terrorism, and as a result, are attacked.32 The sex of Syrian refugees in the US complicates the interpersonal targeting. Women who wear the hijab are more conspicuous than men. Men become easy targets if they have “Muslim” names.31 Additionally, policies like the Patriot Act, and those on “Countering Violent Extremism,” have disproportionately caused Syrian Muslim refugees to be targeted.33 All of these experiences, impact the mental health of Syrian refugees in the US.

Meaningful Employment

Refugees arriving in the US for permanent resettlement are assigned to a resettlement agency to provide case management and financial and/or housing services for between 30 and 180 days.34 Helping families find employment and to become financially independent is a priority of US resettlement agencies. Thus, overall employment rates for male refugees including those from Syria are higher than that for US-born men (67% vs. 62%).34 Although unemployment rates for Syrian refugees in the US are generally lower compared to US citizens, Syrian refugees have higher rates of underemployment than US citizens. This is either because most of them are a poor fit for their jobs, possess higher skills, have more education than their job requires, have medical licenses that are not recognized in the US, or cannot speak English.35 Underemployment leads to poverty, a reduction in life satisfaction, and demotion in social status, which ends up impacting the mental health of Syrian refugees. It is therefore important to assist Syrian refugees to find meaningful employment after settlement in order to prevent social marginalization, isolation, and deterioration of their mental health.

Lingering Concerns About Relatives Still in Syria

Due to the war, some Syrian refugees that resettled in the US were separated from their families. Family separation breaks social connections and often results in the formation of new and smaller networks with less capacity to support one another. In families headed solely by women, there are many challenges.36 The absence of key family members increases financial burdens and debt, creates poor relations with host communities, and raises stress levels.

Barriers to Mental Health Seeking Behavior

The inability to speak the English language, stigma, lack of adequate insurance and transportation, as well as poor health system acculturation are some barriers that account for the lack of mental health care-seeking behavior among Syrian refugees in the US.

Language

Language has been identified as one of the main barriers to seeking mental health care among Syrian refugees in the US. In a qualitative study conducted in California on Syrian refugees, a study participant said, “the number one challenge is the language.” He stated that there is a communication gap between Syrian refugees and mental health care providers and that using translators does not always help.18 According to another participant in that same study, after having two fainting spells upon arriving in the US from Syria in 2016, she had two emergency room visits but was misdiagnosed. It was only after a caseworker from the Syrian Community Network smoothed communication between a medical interpreter and a surgeon during a third visit that she finally received lifesaving brain surgery. 18 There are relatively few trained medical interpreters in the US who speak Arabic, and where they are available, they are in high demand.18

A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to mental health services access among refugee women in high-income countries, including Syrian refugees in the US, found that the limited grasp of the English language served as a barrier to understanding health systems and medical terminology, and thus, hindered appointment scheduling, and caused missed clinical appointments.37 Donnelly et al. found that the language barrier also interferes with refugees benefiting from available mental health counseling services and community-based health programs.37

Stigma

Stigma is the extreme disapproval of a person or group of people based on certain characteristics that distinguish or make them undesirable by other members of society. It is also a set of negative and often unfair beliefs that a group of people have about something.38 Historically, mental illness is stigmatized within the Syrian community. As pointed out by Hassan et al., being labeled as mentally ill in Syria bears the risk of one being viewed as “mad” or “crazy,” as well as being seen as personally flawed, which could bring shame upon oneself, family members, and friends.39 Thus, although the literature shows that many Syrian refugees in the US have mental health issues, their utilization of mental health care services is very low.40 This is an issue, as not seeking care early can result in worse mental health consequences and poorer quality of life.

Lack of Access to Adequate Insurance, Transportation, and Health System Acculturation

As part of the US government's refugee resettlement program, Syrian refugees qualify by income for Medicaid for the first three months in the country, after which they are on their own to maintain coverage and get care. Medicaid is a government-run health insurance program for low-income people.18 As of November 2022, 18 states in the US had not expanded Medicaid under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (popularly known as Obama care in the US). Thus, refugees in those states did not have access to longer-term Medicaid coverage.41 Due to inadequate coverage, Medicaid hinders Syrian refugees who are willing to utilize mental health services. The cost of mental health care services, often characterized by prolonged treatment, also prevents Syrian refugees from utilizing services.

In the state of Georgia, some Syrian refugees indicated that the lack of access to transportation prevented them from seeking professional mental health care.28 For newly resettled refugees who do not own a car or have the means to lease a car, learning to navigate the public transportation system can be a challenge. There is a relationship between acculturation and mental health outcomes. Acculturation challenges such as the lack of culturally appropriate services, care preferences, cultural norms, religious beliefs, and expectations also impact Syrian refugee mental health-seeking behavior.42 Once in the US, Syrian refugees face linguistic, cultural, and economic burdens, which are often compounded in the mental health services sector. Many of them find themselves unable to bridge the health culture and linguistic barriers that come with trying to access health services.42 Thus, they are left in the difficult position of trying to navigate trauma and transition, which are disempowering, and lead to the non-utilization of available services.

Conclusion

Generally, refugees often experience mental health issues based on what it is that they are fleeing from. To meet their mental health needs, it is imperative for host countries to put in place mechanisms to screen for and address the mental health conditions they bring along with them, and the determinants in the host country that could put them at further risk. While the US is accepting and resettling Syrian refugees in various parts of the country, it is also important that it focuses on and invests in the mental health needs of the refugees so as to improve their physical and mental well-being. Evidence suggests that language, stigma, lack of access to adequate insurance, transportation, and poor health system acculturation serve as barriers to the mental health-seeking behaviors of Syrian refugees in the US. Thus, specifically creating a federal certification program that uses already resettled refugee medical translators will ensure that medical translators are available in the US and translations are more accurate. Destigmatizing mental health within the Syrian refugee community in the US will improve upon their mental health-seeking behavior, and expanding Medicaid in all states in the US will help to provide Syrian refugees with longer-term health coverage for their mental health needs. Helping Syrian refugees familiarize themselves with bus schedules and routes, as well as becoming comfortable with health systems in the US, will help to relieve stress and improve upon their mental health care-seeking behavior.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest:

The authors declare no competing interests.

Financial Disclosure:

Nothing to declare.

Ethics Approval:

Not Applicable

Disclaimer:

None.

Acknowledgment:

None.

Funding/Support:

There was no funding for this study.

References

- Mental health inequities and disparities among African American Adults in the United States: The Role of Race. Research in Health Science. 2020;5(3):3048.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Key terms and definitions in mental health. WHO; Published 2022 (accessed )

- About mental health. CDC.gov.; Published 2022 (accessed )

- Overview of research on the mental health impact of violence in the Middle East in light of the Arab Spring. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(9):625-629.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preventive strategies for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(7):591-604.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Web MD. Published 2022 (accessed )

- Study Smarter. Published 2022 (accessed )

- The interplay of environmental exposures and mental health: Setting an agenda. 2022. Environ Health Perspect. 130:25001.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alliant International University; Published June 19, 2018 (accessed )

- Influence of environmental factors on mental. Healthmed.org. Published March 1, 2021 (accessed )

- Environmental stressors: the mental health impacts of living near industrial activity. J Health Soc Behav. 2005;46(3):289-305.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health and stress-related disorders. CDC.gov.; Page Last Reviewed June 18, 2020 (accessed )

- Utilization of mobile mental health services among Syrian Refugees and other vulnerable Arab populations-A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1295.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health consequences of war: a brief review of research findings. World Psychiatry. 2006;5(1):25-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ibor JJ, Christodoulou G, Maj M, eds. Disasters and Mental Health. Chichester: Wiley; 2005.

- [CrossRef]

- New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):240-248.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of possible mental disorders in Syrian refugees resettling in the United States screened at primary care. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(3):664-667.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Health News. Published September 18, 2018 (accessed )

- Why has the Syrian war lasted 11 years? BBC News. Published March 15, 2022 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- The impact of the Syrian conflict on population well-being. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3899.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2021 humanitarian needs overview: Syrian Arab Republic. Published March 31, 2021 (accessed )

- The New York Times. Syria's mental health crisis. Published August 1, 2014 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees resettling in high-income countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open. 2020;6(4):e68.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The US refugee resettlement process explained. USA for UNHRCR The UN Refugee Agency; Published July 21, 2022 (accessed )

- Arrivals of Syrian refugees in the United States FY 2011-2022. Statistica. Published October 12, 2022 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Syrian refugees in the United. Migration Policy Institute; Published January 12, 2017 States. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/syrian-refugees-united-states-2017#:~:text=In%20total%2C%2018%2C007%20Syrian%20refugees,2011%20and%20December%2031%2C%202016 (accessed )

- Mental health of resettled Syrian refugees: a practical cross-cultural guide for practitioners. J Ment Health Train Educ Pract. 2019;15(1):20-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health status and service assessment for adult Syrian refugees resettled in Metropolitan Atlanta: A cross-sectional survey. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019;21(5):1019-1025.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racism Without Racists: Colorblind Racism and the Persistence of Inequality in America. London: Rowman & Littlefield; 2014.

- Latino immigrants and the U.S. racial order: how and where do they fit in? 2010. Am Sociol Rev. 75:378-401.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The racialization of Muslims: Empirical studies of islamophobia. Critical Sociology. 2015;41(1):9-19.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Racialized political shock: Arab American racial formation and the impact of political events. 2016. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 39:2722-2739.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The evaluation of the Refugee Social Service (RSS) and Targeted Assistance Formula Grant (TAG) programs: Synthesis of findings from three sites. The Lewin Group Ingenix Company; Published March 2008 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- How are refugees faring? In: integration at U.S and state levels. Migration Policy Institute; Published June 2017 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of separation on refugee families: Syrian refugees in Jordan. Reliefweb. Published May 30, 2018 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- If I was going to kill myself, I wouldn't be calling you. I am asking for help: challenges influencing immigrant and refugee women's mental health. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(5):279-290.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam-Webster. Published 2022 (accessed )

- Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Syrians affected by armed conflict. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25(2):129-141.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental health self-stigma of Syrian refugees with posttraumatic stress symptoms: investigating sociodemographic and psychopathological correlates. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:642618.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assessing perceived barriers to healthcare access for restricted refugees in the western United States. Digital Access to Scholarship at Harvard. Published May 20I8 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]

- US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Center for Disease and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases. Syrian refugee health profile. Published December 22, 2016 (accessed )

- [Google Scholar]